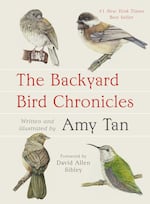

Amy Tan might be best known for her fiction, including “The Joy Luck Club” and “The Kitchen God’s Wife,” but her latest book takes its drama from her backyard bird feeder. In 2019, Tan began drawing birds she saw in nature, particularly the ones who visited her tree-filled backyard in Northern California. The result is a book of reflections, observations, detailed drawings and cartoon sketches called “The Backyard Bird Chronicles.”

Courtesy of Penguin Random

Amy Tan might be best known for her fiction, including “The Joy Luck Club” and “The Kitchen God’s Wife,” but her latest book takes its drama from her backyard bird feeder. In 2019, Tan began drawing birds she saw in nature, particularly the ones who visited her tree-filled backyard in Northern California. The result is a book of reflections, observations, detailed drawings and cartoon sketches called “The Backyard Bird Chronicles.” Tan spoke to us in front of an audience of students at Franklin High School on Oct. 9, 2024.

The following transcript was transcribed digitally and validated for accuracy, readability and formatting by an OPB volunteer.

Dave Miller: This is Think Out Loud on OPB. I’m Dave Miller, coming to you in front of an audience at Portland’s Franklin High School. We are spending the hour today with the writer Amy Tan.

[Applause]

Amy Tan took her first drawing lessons at the age of 64. But you would not know that based on her new book. “The Backyard Bird Chronicles” are made up of Tan’s journal entries and elegant drawings of birds that she saw in her backyard. She began the project in 2016 not for the public, but for herself as an escape from the hate and divisiveness she saw in the human world. And then birds became, in her words, “an obsession.” “The Backyard Bird Chronicles” is the fruit of that obsession – a book about curiosity, attention, and even love. About what happens when you sit with and try to better understand the nonhuman lives in our midst.

Tan is the author of two memoirs, two children’s books and six novels, including “The Joy Luck Club.” Last year, she was awarded the National Humanities Medal. It’s my honor to welcome Amy Tan to the show. Thanks so much for being here.

Amy Tan: Thank you.

Miller: Since we are with a whole bunch of students, I want to start with a student question. What’s your name? And what’s your question?

Audience Member: My name is Iris. My question is, what was the spark that inspired you to pursue writing as your chosen career over your previous job? And what was what or who gave you the courage to do that?

Tan: You know, I think a lot of people believe that it started in childhood. I had written for a contest, an essay called “What the Library Means To Me: An Essay.” But it wasn’t really until I was an adult that I started to write fiction. And it came from feeling very dissatisfied, writing about things that other people wanted me to write about, business writing. It was so unfulfilling. I needed to find meaning in my life and I started to write fiction.

Miller: I love the second part of her question. It’s what gave you the courage to do that? Because you had what seems like a stable job. It seems like it wasn’t fulfilling. But what made you say I’m gonna try something that’s so much riskier?

Tan: Well, it wasn’t risky because I didn’t dream of becoming published. This was something, just like the bird journal, that I could do in the privacy of my home. I could write the stories for myself. There was a compulsion to do that, not something that I had to think about that others would read and criticize, or anything like that. Now, if I knew it was gonna be published, that would have been a different thing, and I probably wouldn’t be finished by now because I would be so paralyzed with the idea that somebody would read it.

Miller: Are you talking there about what you first wrote, the first stories that became your published novel? Or your latest book?

Tan: Both. What’s wonderful about writing “The Joy Luck Club” and also writing “The Backyard Bird Chronicles” is that I had no intention of it being published. And when somebody else decided that it should be published, by then it was mostly done. But when I knew that I would write another novel, and that indeed it would be published, I was paralyzed. But because of that, I do understand that it would require overcoming a lot of self consciousness, if you are going to start a novel and know that somebody will read it.

Miller: Let’s turn to this new book. How much attention had you paid in your life to birds before 2016?

Tan: I saw birds probably in the way most people do. You see these flying objects, “Oh, there’s a crow.” But then you don’t go any further than that. As a kid, I loved looking for other kinds of creatures, snakes, lizards, frogs. And I probably didn’t look up as much. I was nearsighted. And I think this is true for a lot of kids – you’re on the ground, you’re playing somewhere, and you’re not looking up the whole time. So that was natural. It wasn’t really until 2016 that I deliberately paid attention to birds, and saw that they were actually quite remarkable.

Miller: What changed, what led to that?

Tan: I was depressed in 2016. There was a lot more racism going on. It was overt. Some of it was directed to me, as it always had been, but not in the degree of verbal violence that I experienced in 2016. And it was directed to Asian Americans. I felt dehumanized, I felt vulnerable. I needed to get away from these thoughts that were very ugly, and go find beauty in nature. That was a deliberate decision; to do that, to go into nature journaling, and to do what was a childhood dream, to draw.

Miller: Why birds though? This is something that hadn’t really been the focus of your attention before. And then when you sought a kind of escape from, as you said, the verbal violence of the human world, birds were there. Why?

Tan: Nature journaling, you could look at anything in nature, leaves, trees, landscapes, animals, mammals. The lessons that I took from an educator artist named John Muir Laws looked at ways to draw many different things. But when I got to the class about drawing birds, I was instantly hooked. Here was a creature I was sort of familiar with, but there’s so many things about a bird I had never noticed. And then, because I can’t drive, I realized I didn’t have to really go in a car with somebody to the park or a reserve. I could do it in my own backyard. I happened to have a very lovely backyard where there are a lot of birds.

Miller: A surprising number. Can you give us a sense for – and not the entire list because we have limited time here – the bird diversity just in your backyard?

Tan: Before I really got into birds, I noticed three birds: a crow, a hummingbird of some kind, and what I thought was called a bluejay, which was really a scrub-jay. I now have seen 71 different species. And that’s from paying attention. There everything’s from great horned owls which are in our tree today. A wrentit, which you hardly ever see. Robins, titmice, dark-eyed juncos, and many other beautiful, amazing birds.

Miller: Why is your backyard such a haven for so many different kinds of birds? Or is that not unusual? If we really pay attention, will many of us see that many birds in our backyards?

Tan: I think I have a very bird friendly yard. And for one thing, it’s an oak habitat. I have massive oak trees. And that means that there are certain birds like chickadees and oak titmice, who really love that kind of environment and would come. And I have a garden in another area of succulents that are flowering. I have trees that have nectar for hummingbirds. And I have about 20 bird feeders that contain everything that a spoiled bird would want to eat, and appeal to many different kinds of birds … from suet to seeds to live meal worms, which are not worms at all but beetle larvae. I have very carefully cultivated a bird bistro.

Miller: Can you give us a sense for how many beetle larvae, mealworms you provide every month to these birds to make, as you say, this bistro run?

Tan: Well, I started with about 1,000 and those were gone in about two days. And I started buying more and more, and then it got up to 20,000. Because they’re larvae, I had to stop their transformation into beetles, which to birds makes them inedible. And to do that, I had to put them in the refrigerator – 20,000 mealworms. I have a very understanding husband, and he never complained until I reached 20,000. And then he said “Amy, we have no more room in the fridge for the dog food. That tells you what our priorities are.” Instead of buying fewer mealworms, we bought another refrigerator.

[Laughter]

Miller: I did not see that one coming. You didn’t put that in the book.

Tan: We bought it after the book was published.

Miller: So that does say something about priorities. That’s, I suppose, a physical example of what you call an obsession. How much did this take over your life?

Tan: First, let me say that I am obsessive by nature, that’s part of who I am as a writer. I’ve done other obsessive things. I fell in love with dogs, and I went into the dog show world and took a puppy … to becoming the number one Yorkshire terrier in the country, won at Westminster in breed. That is an obsession.

I became obsessed with birds, it was the same thing. I had to learn everything about these birds. And that provided for me, more so than dogs, a feeling that I was seen more deeply in the world and more deeply in myself. So that obsession was rewarded.

Miller: You stayed where you were. It’s in the title, “The Backyard Bird Chronicles.” You weren’t going and sitting and sketching in some meadow somewhere. You stayed in your backyard. Who came to you, and from how far away?

Tan: Well, one of the earliest birds that came to me was a hummingbird. And you always think of these birds as being so delicate, small and afraid of people. But that is truly about the bravest bird that I have in the backyard. I had a little feeder that I bought. I heard that you could lure these hummingbirds to feed out of your hand. And I thought it was a scam. But it was only $2. So I bought this feeder. I started by putting it farther away from me, and then closer and closer. And then the second day, I put it on my hand. The hummingbird came right to my hand, sat there and started to drink. How could you not fall in love with a hummingbird that does that?

Miller: Could you feel the weight of a hummingbird?

Tan: It was almost weightless. I think they weigh about as much as a dime. But I could feel its tiny little feet. They’re very scratchy little feet. And I could see the feathers. I’m looking at this hummingbird from this close, inches away. I am seeing the pattern of the feathers, the white feathers around the eyes, the very dark shiny black eyes looking at me as I talk to it.

Miller: One of the things that I found moving was how open you were about acknowledging that you would fall in love with birds that would acknowledge you. When birds would pay attention to you, and then often go back to their bird business, it would make you like them.

Tan: It was the “Doctor Dolittle” dream – you have a special aura, the birds would come to you. But I realized they’re not all gonna come to me. I could be in my yard and the bird would be doing something and would not fly away once I came into the yard. I would be quiet. The bird would be drinking, feeding or grooming, and it would look up at me, and then it would go back to what it was doing instead of leaving. And that to me meant that it accepted that I was part of its world. It accepted that I was not going to be a predator, just as much as I knew that bird was part of my world.

Miller: If you didn’t know what month it was, and I put you in your backyard and you saw an assemblage of birds, could you tell me more or less what season or what month it was at this point?

Tan: In many cases, I could. If I see a lot of fledglings, I know it’s spring. It could be May, June, July, depending on the fledglings I see. If I see a bird that I don’t see normally year-round, say, a fox sparrow or a hermit thrush, then I know that we are entering into fall migration. If I see certain other birds, we’re later into the winter and these are birds that are overwintering. If I hear owls dueting in my yard, it’s probably October or November.

Miller: Let’s turn to some of the specific birds that you fell in love with, or had other kinds of feelings about, including a kind of serious respect for the ingenuity of scrub-jays. How did you develop that respect?

Tan: First of all, you have to realize that scrub-jay is a fairly big bird compared to the songbirds in the yard. You might have seen birds that are like that here in Oregon. This bird has a very loud squawk, and it’s very clever. It is a corvid, like crows and ravens. And so it can be persistent, patient, and try all kinds of strategies to get into the feeders and empty them before the songbirds can get to the food. It will try it from different angles. It will pull out things and move a dish closer to where it is so it can feed. It will stick its whole head in an opening about an inch-and-a-half square, which is a very dangerous thing for a bird to do because it could be attacked from behind or in front. That is the intelligence of a scrub-jay that needs to eat food, and will do certain things, take risks, to stay alive.

Miller: I’ve used the word “love” a couple of times because that’s the word you use in the book to describe the Anna’s hummingbird that you mentioned earlier that ate from your hand. What do you mean when you say you love these birds?

Tan: When you think about the word “love,” what does it encompass? What does that love incite in terms of your behavior? One is protectiveness. One is always thinking about what that person, that bird, needs throughout the day or to protect itself. It’s food, it’s considering what’s dangerous, it’s considering habitat. It is putting myself in the mind of the bird, and looking at the world from the bird’s perspective.

Now, consider that corvids, hummingbirds, songbirds, hawks, all those birds, only 75% of them are alive by the time they’re adults. So when you look at a bird, and the bird is not a baby or a juvenile, that bird has gone through a lot. And it’s kind of a miracle that it’s there in front of you. So it has given me such joy, pleasure and beauty. How could I not return, in kind, protection, food, habitat that fosters its ability to thrive?

Miller: You give us an example about the challenges that these birds face by writing about one of them. Anna’s hummingbirds, you say that during daylight hours, they feed every 15 minutes, be it a tiny insect or nectar from flowers or feeders. If they don’t consume enough food often enough, they can die during the day. If they’ve not eaten enough before nightfall, they can die while asleep. How have you come to think about the tenuousness of these small lives?

Tan: I came to an understanding pretty quickly that each day is a chance for a bird to survive. If birds don’t get enough food, especially young birds, they might die within the day, or within two days. And I thought so much about the nature of survival, not just among birds, but among all kinds of animals. And then also about humans and survival, and what people have to do to survive. We, in this country, don’t have the same kinds of constraints and difficulties that others in other countries have. But I still think it’s important for me as a writer to think about those difficulties of survival. That is because I’m a writer, and I have to embrace the whole notion of human nature and humanity.

Miller: Let’s get another question from one of the students here.

Audience Member: I’m Wyatt. My question is, do you think that your first novel, “The Joy Luck Club,” had the effect on readers that you wanted?

Tan: I’m the kind of writer, believe it or not, who writes for myself. I’m not thinking about other people. I’m not thinking about readers. After the book was published, I did think about critics, and that I didn’t want to think about them. But in effect, I had to not think about other people reading this, because I would become self conscious. I had to write this for myself. I had to write something that was deeply personal. And I knew that in doing that, the more personal you are, that I had a better chance, actually, of it being more universal, that I would reach readers like you. I don’t know what kind of needs you have or what interests you have, what you love. But if I were to write from a place of absolute emotional truth, it doesn’t matter that the situations I write about or the characters that I write about are nothing like that of your own lives. That emotional truth is the one that you might connect with.

Miller: Has that approach to writing, and really focusing on what you want, what matters to you, what’s true to you, been harder to maintain as you’ve become more well known? At first, for “The Joy Luck Club,” you didn’t know that this was gonna be public. Besides this most recent book – which is a kind of a different beast, a journal that turned into a book – since then you’ve been a known quantity in the publishing world with an editor and a part of this official publishing world. Can you still try to ignore your future readers?

Tan: No. The easiest book for me to write was “The Joy Luck Club” because I didn’t think it was gonna be published. Who would want to hear stories about a bunch of Chinese Americans and weird mothers and daughters. I thought that was this experience only I had had, nobody would identify with it. So I was free to write whatever I wanted. And I was so taken aback that many people were reading it. I became very distressed, actually. I became depressed because this was nothing I had ever dreamed about. I was so stressed, I broke three molars. I would break out into hives. I cried the day that the book was published, out of this fear that my life would change. And it did change.

So I had a very difficult time writing the second book. I felt that there were people looking over my shoulder, and all the words from the worst reviews were right there hanging over my head. The worst critics were looking over my shoulder. And I lost my confidence as a writer for a very long time. I tried writing probably about seven second novels, and I just had to throw them away. I thought people, a lot of people, were waiting for me to fail, and say “she was a one-off.”

Miller: Do you still read critics?

Tan: No. I can’t read critics. I have actually read something, what people have said about this book. It usually was my editor who would tell me what had been written. But there was a point early on, by my second book, in which I told people “Do not tell me anything about what has been said about this book. I don’t want to hear about reviews, good or bad or mediocre. I do not want to know where I am on a list. I do not want to know how much money I’m making.” And that was the thing I had to do to be able to keep my mind focused on the writing itself.

Miller: Let’s take some more questions. What’s your name? What’s your question?

Audience Member: My name is Ines. What is some advice you give to aspiring young authors on finding their voice when it comes to writing about their perspectives?

Tan: Oh, great question. Here’s the question that I asked myself from the beginning when I was starting to write fiction. Somebody had said to me looking at a page or a story that I’d written for my very first creative writing workshop, a conference called The Community of Writers, I had a private session with a published writer I admired. She said “What you’ve written is not really a story. It is the beginning of about a dozen stories. Here’s a voice, here’s another voice. Here’s the beginning of a story, here’s another beginning of the story.” And that question came to me: what is voice, and what is story? And it’s a search that you have for your entire time that you will be writing fiction, looking at which comes first. Do they come together?

The voice in my opinion is the way that you think about the world. It includes all of your experiences that troubled you, that became crises, that made you really think as you sat alone in your room and contemplated that you weren’t understood, this wasn’t fair. All of those things are part of the formation of your voice. And so you can pay attention to it.

And I think what would really help is if you kept a journal and wrote some of that down. This is not a journal about who you saw that day or what you ate. This is a journal about your thoughts, as weird as they are, or what somebody said and what you thought instead. And the one bit of advice I’d also give you is put a star or some notation that the thoughts that you put down in there are originally yours. Because there are many writers who get in trouble, they’ve quoted somebody and then they forget that wasn’t their quote and they’ll put it in somewhere and get charged with plagiarism.

Along with voice then, I think you come to understand a little bit more about the stories you can tell, uniquely you can tell. You are the guide to that universe that you create.

Miller: Let’s take another question. What’s your name? What’s your question?

Audience Member: My name is Emma. And my question is who inspires you the most to write?

Tan: Well, a lot of my inspiration are people who are dead. So that would be my grandmother and my mother. And I say that because they are people who are embedded in me, and know me. And when I write, I have to be truthful. I can do a lot of fancy writing and make it sound like I know something and I feel something. But if I think about those people who know me well, or my grandmother died before I was born, but she was always evident in my mother, there’s a lineage there. And so I think about those people and I have to be truthful. I have to go deeper. So they are my inspiration.

There are many writers, however, who I admire, and when I read their books, I am inspired, I do pay attention. One of them is Louise Erdrich, especially her first book collection, “Love Medicine.” And also, if I wanna start a book and be inspired, I might read “Love in the Time of Cholera” by García Márquez. That first sentence is a killer. So taking inspiration from reading is a good way to get going with the writing.

Miller: One more question right now.

Audience Member: My name is Jake. You started your adult life writing about economics, which is something which is fairly nonfictional and tangible. Can you describe your process transitioning to writing fiction, which is a lot more nuanced?

Tan: So there’s a huge difference. Business writing is writing what somebody tells you to write. They want me to write about telecommunications and how to sell more controllers for a network, or they want you to write about employee motivation, or speeches, or whatever. That is something assigned to you. That doesn’t come from any impulse within me to write about those subjects. So writing fiction however, that impulse, that need to write comes only from me, and I am the only person who can determine what I should write, what I need to write. So that to me is the biggest difference.

What I can learn from business writing is deadlines, which I failed to do with fiction. Or I can learn a little bit about craft, how you start an article, how you start a perhaps a story. I can learn a lot about good writing and bad writing. But I cannot learn the actual compulsion to write. So to me, that is the biggest difference. You have all the things you need to write inside you, whether you know it or not. It’s all the things that have happened to you since the day you were born.

Audience Member: Hello there, my name is Sydney. My question for you was, do you believe the artistic nature of writing impacted your abilities as a visual artist? And if so, how?

Tan: I read an interview that was done with my father when I was six years old. I just happened to find this in a book. I was part of a longitudinal study on early readers. And my father had said something interesting to me in there. He said that even before the age of four, I liked to draw pictures and then tell stories about them. I actually believe that when I was little, those two things happened simultaneously, that I had this story and I was drawing it at the same time. And that’s what I feel about my writing. When I’m writing a novel, I’m imagining a scene, I am seeing it as I write. So I’ve had practice for a very long time doing essentially what I was doing when I was nature journaling – seeing the birds, observing what they were doing, and doing sketches at the same time.

Now what’s in this book are not just these very detailed portraits of the birds, there are sketches of behavior, and that was the kind of drawing to me that was much more important. It was more like a diary, a memento of what I was thinking at the time. So I do think that fiction prepared me for what I was going to do with drawing, and vice versa. It had to do with observation, and coming as close to what I was seeing, and observing, and thinking, and believing as I could make it.

Miller: It takes bravery in my mind to embark on something new … even though you’re saying that you see a connection between writing and drawing, and observation as sort of the tie between them that goes back to when you were four or five or six. Nevertheless, you did write that you took these drawing lessons for the very first time at the age of 64. What was it like to be a beginner at something at that age?

Tan: I first was drawn to it by absolute love. It was something that I’d wanted to do since I was a kid. But I had a subterfuge, and that was I wanted to post these things on a nature journal page and share what we were seeing in nature. I took a pseudonym, and I use my Chinese name. So nobody knew who I was. I could be as good or as bad as I happened to be. But if I had started drawing this, and people knew I was drawing something and they could look at it from the beginning, it would have been frightening, it would have been horrifying.

What you see in the book however, I do have to emphasize, because a lot of people they’ll say, “oh, you’re so talented,” and the common phrase that people say to anybody who draws birds, “better than Audubon,” which it’s not. But it was the fact that I took these classes, and then I practiced using what I call “pencil miles.” That is a term John Muir Laws uses. Pencil miles means practice, drawing the birds heads from different angles, thousands and thousands of hours, as part of the obsession and part of the necessity that you have to do as a writer, as an artist.

Miller: Let’s take another question from the audience. Go ahead.

Audience Member: Hi. My name is Helena. I was wondering, going back to what you said earlier, that considering that publishing the books and “The Joy Luck Club” made you so emotionally overwhelmed, depressed and everything, if you had the chance to go back in time and undo the fact that your books were published, would you do so? Or do you think that there have actually been more positives from the experience than the negatives?

Tan: Wow, that’s an interesting question. If I were to go back knowing what I know now, I would tell myself that I still have to go back to the original impetus for writing. And that is writing for myself, writing to discover things about myself, and especially to make sense of what’s happened in my life, and as a consequence, how I see life now, what my morals are, what my ethics are, what I think about humanity and my responsibility to humanity. And I would say to myself that is more important than anybody being critical of what I have to write. Going into it then with that, I might not have been so terrified about what was happening.

And you have to realize I didn’t dream of being published. I know that sounds disingenuous, but it’s absolutely true. I dreamed of publishing a short story in a good literary magazine by the time I was 70. And I made it.

Miller: Let’s take another question.

Audience Member: Hello. You brought up your mother. After reading “Mother Tongue,” I was wondering how you went from being ashamed of being embarrassed about her so-called “broken English,” to accepting it and embracing it? And also what was your mother’s favorite book of yours?

Tan: As a kid, I think it was inevitable that I would feel embarrassed because I saw how disrespected she was, and how there were people who wouldn’t listen to her, who thought that her opinions were not worthy of listening to. She got bad service at banks and places like that. But as I got older I came to understand that she was a very intelligent woman, that if she could have spoken perfect English, that the kinds of things that she was saying made a lot of sense. They were pragmatic, they were reasonable, and they were often clever and prescient. But it took being an adult and understanding that to put her voice into a kind of new language, an internal voice that had these thoughts, rather than it being the external voice that the public heard.

Miller: By the way, that’s an essay from 1990 called “Mother Tongue,” which folks can find online. I highly recommend it. Let’s go to another question from our audience.

Audience Member: Hello, I’m Lucy. And I was wondering when you’re working on a project and you begin to feel uninspired, do you find it better to start a new project entirely? Or do you try to look at it from a different angle? What’s your way of going about that?

Tan: Wow, you have described exactly the bane of my existence, and the reason why I don’t have 10 novels. I sometimes think I should do what Joyce Carol Oates does. And that is, she writes every single day no matter what she’s doing, even when she’s on vacation, when she’s at a conference. I think she’d probably keep writing if she was in the hospital. The reason why I think that’s good is that it keeps you in that place in your head, where you’re still in that fictional mind, you’re still in the story.

But I have a very disjointed life. Here I am in Oregon, and I’m talking to you. There’s a trick that I have used in the past and that is when I’m writing, I find a soundtrack that is very complementary to the scene that I’m writing. And often soundtracks like that from The Mission, or others that have full orchestration will provide the mood. And then the next day, when I have to start writing, I put the same music on, and instantly I’m back in the place that I was the day before

But I think the best advice that I don’t follow is to write every day, even a sentence, even in a journal. What I do do is I think about my novel every single day.

Miller: To go back to this new book, there’s nothing overtly about politics in it. Nothing about the 2020 presidential election, nothing about January 6th. But did your project work? I mean, did it effectively give you a distraction from the violence of the human world?

Tan: It was a distraction in the beginning. But then as it took over and became its own thing, it was an alternate world that I could go to, and find that it was more than what was out there. It also gave me a kind of stamina, a way to get rid of the heaviness that I was feeling so that I could go back in the world. I think that it is important for me to be involved in the world, to be involved in things that disturbed me. So I am, for example, working on the election, not just giving money but doing the groundwork. And that is important to me. I don’t think I could have done that before I started doing the journal. I would just sit there being depressed that this is the world that we had now, and that overt racism would always become part of it.

Miller: For a lot of birders, paying close attention to birds makes the destructive tendencies of our own species even more apparent. I’m thinking about climate change and habitat destruction. You do talk about domestic cats and wildfires – they come up here and there in a lot of the entries. How much could birds be an escape from those aspects of the human world, as opposed to a reminder?

Tan: I think birds are more of a reminder, more of an awareness of all of those things, because what we do as humans and what’s happening in the world impacts them so directly and immediately. My obsession with birds, my love of birds is what took me into conservation. I’m on the board of American Bird Conservancy. And so I know about many more threats to birds than the ones that I mentioned in the book.

Now, you have to keep in mind that when I was doing this, I was very new to birds. I didn’t know a lot about what was going on. I didn’t know what bird conservation consisted of. And so I just knew of the elements in my own yard that were going to impact those birds: window collisions, cats. But I now am aware of things like habitat loss or changes in habitat, how global warming might change the seasons, that birds might be going by how much sunlight there is and start migrating back to their homes, and global warming has changed how soon the insects come out of the snow, and that the birds would have nothing to eat. So that is part of it.

But with everything I write, I don’t like to be overt. I do believe with everything that we write as novelists, as fiction writers, does contain a politic mindset within it, because we are after all shaped by the world we live in, the government that we have, the kind of freedoms we have or don’t have. They are assumptions that live within us. And we may not be aware of that until we start to question it. So it is in all of those books, the politics, the concerns about humanity and nature. And in fact, looking at birds and their need to survive made me pay attention much more to humanity and similarities that go on in the world that are reflected in birds. Not to be anthropomorphic, but to see that we as living creatures have similar needs. And that includes destruction, death and survival. I think, in a way, it made me more in touch with those issues that you mentioned.

Miller: Let’s take another question from our audience. Go ahead.

Audience Member: My name is Max. What is your message to Asian Americans today? As the Trump campaign pushes for a new wave of xenophobia and hatred?

Tan: You know, when I was growing up in the ‘50s and ‘60s – and I’m just talking about before adulthood – this country was a lot different, vastly different. I would be in schools where there was not a single Asian kid there. And there certainly were no books, novels written by Asians, Asian Americans. There were no books written by women when I was studying in college, except for Virginia Woolf.

So the world has changed. You see that, beginning to see that more in representation in government. And I believe that more Asian Americans, especially younger people, know that they can have a voice, that they can take that voice and go somewhere and call attention to the concerns. I think people are much more aware that we have to go beyond the stereotype of the model minority, that we’re not a homogeneous group. Asian Americans are very individualistic in their thinking, just as with any group.

That is an understanding that I have. I don’t think as many Asian American young people are as embarrassed of their culture as I was when I was growing up. But it still happens. I’ve heard from many young people who read “The Joy Luck Club” and said, “those are exactly the things that I have, that I was ashamed of my family, that I blamed my culture for not being popular, for not being beautiful,” etc.

Miller: Let’s take another question. Go ahead.

Audience Member: Hi, my name is Audrey. Do you believe that writing almost has a mind of its own? And have you ever realized alternative meetings or interpretations of your work in the writing or editing process? Or do you often realize those after the fact?

Tan: I think we like to say that somehow there’s the muse, the muse takes over, and the book writes itself, instead of it being very, very hard work and a concentration of many things. But at the same time, I also feel that still. There’s a point where I have put together all the elements, I’ve worked so hard at the craft of it to find the narrative, that there reaches a point usually in the last 50 pages where the book suddenly takes on a different kind of force. And it’s as if those pages just come out smoothly. You don’t have to work at them at all. If that’s the kind of muse that has happened, then I am welcoming that muse with every single book I write. I think it has to do also with your own confidence that you have found the story, and it’s going to happen.

I have talked to writers, musicians, artists and they all feel that you get to this point. It’s like an epiphany. And you elevate. There is a feeling that you have that is like no other, and it makes you want to do it forever.

Miller: I want to go back to something you said earlier, that you tried not to be anthropomorphic, to ascribe human feelings or humanness to the birds you were looking at. But you’re a novelist, and the book is full of questions and curiosity that do versions of that, in lovely and interesting ways. I’m curious how you think about the benefits of anthropomorphizing, something that ecologists or biologists frown on, they say that “that’s not science.” But you’re not after science. So what are the potential benefits of it?

Tan: Yeah, I have to say I’m not doing scientific research. Do not use this as a textbook or a guide to birding. These are an amateur, beginner birder getting to know birds and asking questions.

But I was talking to a biologist, a field researcher. We talked about anthropomorphism. In fact, I’ve talked to several of them. And most of them think, there was an old notion that you should not anthropomorphize at all, you should really steer clear of that kind of thing. But today, it’s almost as if anthropomorphism, looking at traits that are analogous to human behavior, is actually a useful jumping off point for examining all the traits of what is going on behavior-wise.

There’s a wonderful biologist named Bernd Heinrich, “The Mind of the Raven.” He even talks about love and murder and revenge, and what those qualities are. They’re not the same as with humans. But there are some similarities in behavior and protectiveness, or whatever it is that we have when it comes to those emotions. And I see it. When you look at a crow, tending to its baby and feeding it and pulling nits out of its head and eating them, how could that not be love? These birds sacrifice a lot. How could that not be love? It’s not human love. It might be, in part, an instinct. But it has the qualities that we see in love. And I think that’s really the more important thing, that we start to ask ourselves, “what are these emotions that we have?” I get prodded, provoked into thinking about them when I look at the behavior of birds.

Miller: That phrase you mentioned that you got from your nature journal and your drawing teacher is “pencil miles.” And you said you spent thousands of hours of pencil miles – meaning, sitting there day after day, drawing, looking, drawing, looking, and drawing. How do you think that changed the way you see when you’re not looking, or just changed the way you see the world around you on a day to day basis?

Tan: I notice more details in everything, especially when I’m in a new place, and I’ve had more sleep than I’ve had in the last three days. But I might see, for example, rolling hills as I’m driving by. And I look first at what color would I use to represent the color of those hills? What would I do in terms of the shape to simplify it, get the gestalt of what I’m seeing. And then I start to notice details in ways that I never would have paid attention to before. I might notice things about people.

I’ve always been a good observer, but now I’m looking at patterns in a different way. That’s what I gained from those thousands of hours of looking at birds. That if you look at something, there are both individuals out there. But there are commonalities. And that comes through in the way of patterns, context and circumstances. So I have a way now of organizing in my mind how I look at different things in the world.

Miller: Do you still have a daily drawing practice?

Tan: I do not. And in part, I have forced myself to go back to writing my novel. And if I were to start doing the drawings, then I would end up doing that for hours at a time. I had to force myself not to do that. I now have my office in front of a window that has the blinds closed, so I can’t see the birds.

Miller: Why? It seems like a kind of self denial.

Tan: It is. But if you’re obsessed with two things, you have to give in to one obsession. If you’re in love with two countries and you want to live in two countries, you can’t live in them at the same time. You can take turns. And so that’s how it is for me.

Miller: Time to live a little bit once again in the world of novel writing.

Tan: Yes, yes.

Miller: Amy Tan, thank you very much.

Tan: Thank you.

Miller: Thanks as well to Ayn Reyes Frazee here at Franklin High School, and Olivia Jones-Hall at Literary Arts for making the show possible. And a huge thanks to our so many great questions from our audience of students here.

Contact “Think Out Loud®”

If you’d like to comment on any of the topics in this show or suggest a topic of your own, please get in touch with us on Facebook, send an email to thinkoutloud@opb.org, or you can leave a voicemail for us at 503-293-1983. The call-in phone number during the noon hour is 888-665-5865.