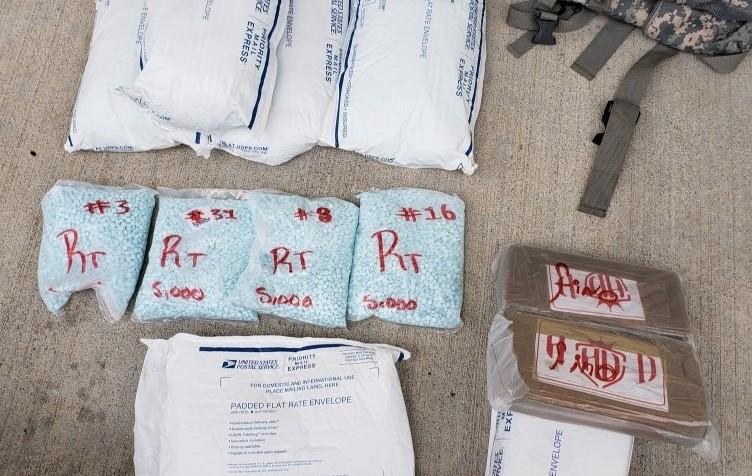

Seizure of fentanyl by Oregon State Police in this undated supplied photo.

Courtesy of Oregon State Police

The number of people dying from drug overdoses continued to increase in Oregon and a handful of other western states even as it dropped in much of the rest of the country, according to new federal data.

Oregon drug overdose deaths grew 22% during a 12-month period ending in April 2024, according to the preliminary data. That’s the second-highest rate of increase in the nation — even as overdose deaths dropped 10% nationwide.

Nationally, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data offers good news after years of skyrocketing drug overdose deaths. In Oregon, however, the numbers present a bleak and more complicated picture. State lawmakers ended Oregon’s much-debated experiment with drug decriminalization in September, and the new numbers will likely only fuel lingering debate over whether rolling back Measure 110’s decriminalization was a good idea.

Alaska saw a 42% increase in fatal overdoses in the same 12-month period, while in five western states the increases were less than in Oregon: Nevada (18%), Washington (14%), Utah (8%), Colorado (4%) and Wyoming (2%).

East of the Rockies the only reported increases occurred in Iowa and

Related: Latest data show overdoses continue to skyrocket in Oregon

the District of Columbia, both by about 1%. Montana reported no change, while overdoses in other states decreased between 1% and 30%.

So what’s happening? While observers have different reads on what the numbers mean, they agree that the spread of fentanyl is a big factor.

Fentanyl wave drove changes

Between 2013 and 2018, fentanyl proliferated in drug markets east of the Mississippi River, causing a 10-fold increase in overdose deaths from synthetic opioids, amid fears that it was spreading west.

In 2019 fentanyl started moving west into Washington, Oregon and other western states. Along with that came what’s been dubbed a “fourth wave” of overdoses in the West, blamed on fentanyl increasingly being spliced into other illicit drugs by Mexican cartels to boost sales and promote addiction.

The increases in the West sparked an interpretation that fentanyl had “nowhere else to go,” Ju Nyeong Park, an epidemiologist and assistant professor of medicine at Brown University, told The Lund Report. Now, she added, “the shock of that increase in that fentanyl supply has reached every part of the country.”

Park said it’s not clear if the drop in fatal overdoses nationally will continue after years of devastation from fentanyl.

The federal government has increased spending on testing strips, overdose-reversal medication, methadone and other measures meant to reduce the harm from using illicit drugs, she noted. Oregon is also seeking to make naloxone, an opioid-overdose reversal medication, more available.

Park recently co-authored a paper published in JAMA Network Open that concluded Oregon’s surge in fatal overdoses in the two years after its decriminalization was about the spread of fentanyl — and not changes to criminal statutes. The paper was funded with support from Arnold Ventures, a pro-decriminalization group that contributed $700,000 through an intermediary to the campaign backing Measure 110.

Such debates over statistics don’t necessarily take into account a number of state-specific complexities, according to health workers and advocates. Measure 110 arrived on the heels of fentanyl even as the pandemic decimated and largely shut down Oregon’s already threadbare behavioral health system — which has consistently ranked as among the worst among states.

And as The Lund Report reported last year, Oregon’s failure to invest in recommended youth prevention measures and treatment made the state’s kids particularly vulnerable to overdoses linked to fentanyl’s spread. Earlier this year a subsequent six-month investigation found Oregon state officials do little to support public school districts in adopting science-based drug prevention programs offering tools and life skills — contrary to how other states tackle the complicated issue.

Related: ‘More than one per day’: Multnomah County report shows spike in fentanyl overdose deaths

In any event, fentanyl is clearly having an effect. In the same 12-month period captured by the new round of federal data, roughly 101,000 people died of overdoses, nearly 69,000 of which were attributed to synthetic opioids such as fentanyl.

In that same period, the per-capita rate of fatal overdoses in Oregon ranked 10th among states, according to an analysis by The Lund Report using U.S. Census population estimates from last year.

Measure 110 debate continues

But as Park’s paper notes, Measure 110 proponents had believed that decriminalization would cause overdoses to decrease.

Tera Hurst — executive director of the Health Justice Recovery Alliance, which backed Measure 110 — told The Lund Report that the new data showing continued overdoses reflect lingering stigma around drug use that prevents people from getting treatment — a stigma that decriminalization was, in part, intended to address.

“Unfortunately, Oregon’s going backwards because we’ve now recriminalized addiction,” she said. “Ultimately, we know that stigma is a big part of what’s killing folks.”

A cake that was served at the grand opening of the Recovery Works NW detox in Southeast Portland on Aug. 18, 2023. The withdrawal management facility was funded through Measure 110.

Emily Green / The Lund Report

Kevin Sabet, a former White House drug policy advisor who was active in the backlash against Measure 110, in the past has noted that even in the midst of a surge in overdoses in the west, the increase in fatalities in Oregon far outstripped those of its neighbors. He argues that contrary to proponents’ belief, the new data shows “decriminalization and normalization of drugs is not going to be a way to reduce overdoses.”

“It really debunks this theory that if you decriminalize drugs, more people will want to come get help,” he said.

Sabet, who worked under Democratic and Republican administrations and has founded an anti-legalization nonprofit, concedes the issue is complicated, and fentanyl is a factor.

The data may reflect that there is more awareness about the dangers of fentanyl on the east coast, he said, adding that the data also raises questions for him about comparative spending on treatment, overdose-reversal medications and the use of “safe injection” sites that allow people to use drugs in supervised settings.

Dr. Todd Korthuis, an addiction medicine specialist at Oregon Health and Science University, told The Lund Report in an email that people in Oregon and Washington are more likely to combine fentanyl with methamphetamine, which increases the risk of overdose.

He said the number of drug overdose deaths in Oregon are comparable to states with more punitive approaches. Oregon saw about 1,900 drug overdose deaths over the 12-month period reflected in the CDC’s data, about the same number as Kentucky, which has a population only slightly larger than Oregon’s.

“We all need to double-down on efforts to prevent people from starting fentanyl,” Korthuis wrote. He called for providing overdose-reversal drug naloxone to people at risk while lowering barriers to methadone and buprenorphine — medications that reduce opioid cravings.

This story was originally published by The Lund Report, an independent nonprofit health news organization based in Oregon. You can reach Jake Thomas at jake@thelundreport.org or via X @jthomasreports