OHSU's Jonah Sacha, Ph.D. says new research could lead to a universal influenza vaccine within five years.

Courtesy OHSU/Christine Torres Hicks

The flu vaccine to end all flu vaccines

This year’s flu shot is rolling out and you’ll likely get the best protection if you get vaccinated by the end of October — before the viruses fully kick off their annual snotty reign-of-terror.

There are many virus strains that cause what we call “the flu.” Every year, the World Health Organization uses disease data to predict which strains will cause the most problems. Then new vaccines are formulated to combat the most likely offenders.

But what if there was a better way?

Researchers at Oregon Health and Science University, the University of Washington and other institutions are working on a universal flu vaccine that could eventually mean your next flu shot will be your last.

Current flu vaccines train your immune system to identify viruses based on their external features — kind of like the way we recognize people based on their faces. But the surfaces of viruses evolve to evade detection extremely quickly, which is one reason we need new vaccines every year.

The new vaccine is designed to teach your immune system to seek-and-destroy based on what’s inside the virus. These innards evolve far slower — so slow, in fact, that when the researchers created a vaccine to recognize the 1918 Spanish flu (H1N1), it offered significant protection to animals exposed to H5N1 (bird flu), one of the most deadly viruses currently in circulation.

The researchers estimate that within five years, this technology could lead to a universal flu vaccine that protects a person for their entire lives.

The paper in Nature Communications can be read here.

This conceptual illustration shows how different treatments can impact the severity of subsequent wildfires in the landscape. Areas that have received thinning and prescribed burn treatments fare better then areas left untreated or with only one treatment.

Courtesy of Erica Sloniker/The Nature Conservancy

Yes, thinning and burning forests does reduce wildfire severity

The 2024 wildfire season is almost over but not before more than 1.2 million acres burned in Oregon. Once the rains start, a round of fall fuel treatments can begin. These treatments — like thinning out forests, pile burning and broader prescribed burning — are designed to reduce the risk of severe wildfire down the road.

But for a long time, it’s been difficult to pin down just how effective the treatments are and which treatments work best.

Researchers with the U.S. Forest Service and The Nature Conservancy analyzed the results of 40 studies and reports that measured the impacts of wildfires burning through treated and untreated forests. They found fire treatments in seasonally dry conifer forests (like those on the east side of the Cascades) can reduce fire severity by more than 70% compared to untreated areas that burn.

The most effective kind of treatment was a combination of thinning and prescribed burns. And while using prescribed burning alone had a significant impact, solely relying on forest thinning didn’t reliably move the needle.

The authors stress that fuel treatments need to be maintained over time. After 10 years, their impact on wildfire severity was significantly lower.

Read more details in the journal Forest Ecology and Management here.

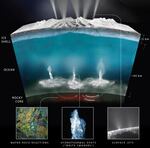

This artistic rendering shows hydrothermal vents on the seafloor of the Saturnian moon Enceladus.

Courtesy of NASA/JPL-Caltech

Earth’s hydrothermal vents could predict life on other worlds

Hydrothermal vents on the ocean floor are widely considered spots where life could have originated on Earth. The combination of heat and chemical energy released as water cycles up through the seafloor creates conditions where organic molecules can link up and form the building blocks of life.

Earth likely isn’t the only ocean world in our solar system, and an international team, including scientists from Blue Marble Space in Seattle, wondered if similar hydrothermal vent systems could exist on one of our celestial neighbors.

The researchers focused their attention on Europa (a moon of Jupiter) and Enceladus (a moon of Saturn), both of which are believed to have liquid water oceans encased in a thick layer of ice. Using a hydrothermal vent system located off the Pacific Northwest coast as a model, they ran computer simulations to see under what conditions vents could form on these moons.

The team found that hydrothermal vent systems could exist under the ice on both moons, despite the vastly different gravities and geology to Earth. And they say the vents could have been active far longer than expected —potentially providing enough time for life to emerge.

Read the paper published in JGR Planets here.

This NASA image captured July 3, 2010 shows ship tracks above the northern Pacific Ocean.

Courtesy of NASA Goddard

Pollution positive, climate negative

Cargo ships out on the ocean are huge sources of greenhouse gases and air pollution — with carbon dioxide, nitrogen dioxide and sulfur dioxide topping the list of offenders. Sulfur dioxide in particular can cause significant respiratory problems in people. In early 2020, new global rules cut ships’ sulfur dioxide emissions by nearly 80%. It was great news for public health, but the impacts of these pollution cuts are playing out in surprising ways for the planet as a whole.

When ships spew sulfur dioxide into the atmosphere, the gas prompts the formation of clouds in the form of ship tracks over the ocean. These long white clouds help reflect the heat of the sun back into space, keeping the planet cool. But when the sulfur emissions decreased, so did the cloud cover.

New research from Pacific Northwest National Lab is showing just how much of an impact the decline in ship tracks likely made in 2023, the planet’s warmest year on record. Their analysis showed the number of visible ship tracks have decreased 25-50%. And in areas where cloud-cover decreased there was generally more warming. The researchers estimated that up to 20% of the record warming in 2023 could be linked to limits on sulfur.

The study was published in Geophysical Research Letters here.

Solar-powered hydrogen fuel

Hydrogen is a clean-burning fuel. Use it to power your car and the only by-product is water. Sounds great, right? Well a challenge for hydrogen comes on the front end — isolating the gas so it can be used as fuel.

The most common way this is done is by creating a reaction between natural gas (methane) and steam to create isolated hydrogen. Problem is, one of the byproducts is carbon dioxide — a greenhouse gas. Hydrogen can also be created by splitting water molecules (H2O) with electricity, but this can be energy-intensive and expensive.

Researchers at Oregon State University are working on what they hope is a better way. They’ve created a new photocatalyst — a chemical that uses energy from the sun to power a reaction — to split off hydrogen from water molecules. The reactions are fast and efficient - meaning it doesn’t take much solar energy to produce hydrogen.

The results point to a new and promising path to explore in developing ways to produce clean hydrogen in a sustainable way.

The research is published in the journal Angewandte Chemie here.

In this monthly rundown from OPB, “All Science. No Fiction.” creator Jes Burns features the most interesting, wondrous and hopeful science coming out of the Pacific Northwest.

And remember: Science builds on the science that came before. No one study tells the whole story.