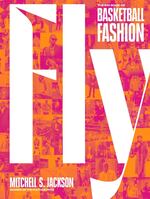

Portland author Mitchell S. Jackson's 2023 book, "Fly: The Big Book of Basketball Fashion," chronicles the relationship between basketball, fashion, politics and hip hop.

courtesy of Hachette Book Group

From the Black Panthers to hip hop, the Shakur family have been leaders of Black political thought and activism in this country. Journalist Santi Elijah Holley chronicles the history of this family in his new book “An Amerikan Family: The Shakurs and the Nation.” Holley describes a group of people committed to resisting the exploitation and persecution of Black people, and creating a space of self-determination through activism, care, violence, and art. OPB’s Prakruti Bhatt talks to Holley at the 2023 Portland Book Festival.

From Dennis Rodman’s hair colors to Michael Jordan’s sneakers to LeBron James’s Thom Browne suits, the NBA has long been a place where players’ style off the courts is talked about nearly as much as their style on the courts. Mitchell Jackson’s latest book, “Fly: The Big Book of Basketball Fashion,” chronicles the relationship between basketball, fashion, politics and hip hop. OPB’s Paul Marshall talks to Jackson at the 2023 Portland Book Festival.

Note: The following transcript was created by a computer and edited by a volunteer.

Dave Miller: This is Think Out Loud on OPB. I’m Dave Miller. We’re going to bring you two conversations today about Black liberation. They were recorded at the 2023 Portland Book Festival. We start with OPB’s Prakruti Bhatt. She spoke with journalist Santi Elijah Holley about his book, “An American Family: The Shakurs and the Nation.” From the Black Panthers to hip-hop, the Shakur family have long been leaders of Black political thought and activism in this country. Holley describes a group of people, from Assata to Tupac, committed to resisting the persecution of Black people and creating liberation through activism, care, violence and art.

[Audience applause]

Prakruti Bhatt: This is a very extensive multifaceted book and we have only 30 minutes. So I’m gonna get right to it. Santi, you start the book off with a quote by Manning Marable: “History’s greatest dangers are waiting for those who fail to learn its lessons. Any oppressed people who abandon the knowledge of their own protest history or who fail to analyze its lessons, will only perpetuate their domination by others.”

In part one of your book, you brought this code to life. It felt like you were telling us: “Are you not seeing this, like it’s history repeating itself all over again and again.” Was that your intention?

Santi Elijah Holley: It really wasn’t my intention until I began working on it. I began working on this book in the fall of 2020. Donald Trump was still president. There’s racial uprising movements happening all over the country. We were still with COVID. There’s so much happening. I just felt like the country was really in turmoil. Like we were just sort of trying to figure out what was going on. And I approached this book sort of thinking, it’s a history book. I’m telling this really rich history. But I started to see parallels to what was going on, just in society, with things that we were going through, with police harassment of Black and Brown people.

So that sort of stayed with me as I was writing the book. I mean, I didn’t intend for it to be rooted in the presence so much, but as I kept working on it and writing it, I really started to see more and more parallels.

Bhatt: Let’s go back to the past. During this revolutionary movement towards Black liberation, it seemed like there was a lot in a name. What was the significance at that point in time to take up the surname of Shakur and also choosing an African name in the sixties and seventies?

Holley: Yeah, that’s a great question. Back then, there’s a movement for sort of pan-Africanism. There’s a movement towards people embracing Islam and shedding their birth names, or they would say their slave names, in favor of more pan-Africanist names or Muslim names.

The Shakurs really got their start in the mid-sixties as a patriarch, Saladin Shakur, who took the name for himself and others. His two oldest sons, people that he mentored, took the name Shakur out of respect to Saladin Shakur. And also, it was a way of aligning yourself with this family or this tribe, really, this community of people who are committed to Black liberation, committed to pan-Africanism, Islam. But really just saying we are a member of this tribe now, we’re ready to do this work for the rest of our lives, we are committed.

And it wasn’t something that was taken lightly to take this name, Shakur. It wasn’t just something that you would just take because it sounded cool. It was saying that you’re making a commitment to the struggle, however it looks and whatever it takes.

Bhatt: Can you introduce us to your main characters: Lumumba Shakur, Zayd Shakur and Afeni Shakur?

Holley: I feel like most of us know Tupac Shakur, obviously. A lot of us know Assata Shakur, and then some of us know Afeni Shakur, which is Tupac’s mother. And that’s sort of where it ends. When I was researching this book and sort of diving into this family and this history, I realized just how many more Shakurs there were and how pivotal they were – Black Panthers, Mutulu Shakur, which is Tupac’s stepfather, was pivotal and a pioneer in acupuncture and holistic healing for drug withdrawal symptoms. Lumumba Shakur was Afeni’s first husband, Zayd was Lumumba’s brother and there’s all these like different Shakurs. And I was trying to put them all together and trying to figure out how the pieces [fit] and because it’s such a rich family and they were all very active in their own way, like they all saw ways that they could contribute. So yeah, those are the main characters.

Tupac really is the starting point but he really isn’t the focus of the book. [It] is like he’s growing up as this book proceeds because he’s a young baby, sort of, at the start of the book. And he grows up surrounded by this family and by elders and the Black Liberation Movement veterans, all [who] are sort of raising him and surrounding him as he’s growing up. So even though he’s not the focus of the book, he’s always sort of like this thread that’s running through every once in a while. He’ll pop in and he’ll be running around like little Tupac. And then you sort of see how he became who he was. Towards the end of the book, you sort of see how he became so knowledgeable about this history because he grew up with this history.

Bhatt: You mentioned Islam, earlier. We’ve seen formerly colonized countries like India, where religion played a really important role in forming identity. What was the connection between Islam and the Black Liberation Movement in the sixties?

Holley: In the mid-sixties, people were really like younger generations of Black activists and Black organizers were moving away from the Christianity of their parents and grandparents. And they’re looking towards other continents, other people and something that they resonated better with. They felt like Christianity, as it was being preached during the civil rights movement, they had moved beyond that. So it was a whole sort of rethinking your identity and aligning yourself with African nations, with African countries, with Southeast nations. It sort of just brought in their world view and to connect with a world community.

And for them, Islam was a way of embracing the sort of larger world community besides just what they had been taught, which is like turn the other cheek. They were really ready to move on past everything from their parents’ generation, nonviolence, integration, all this stuff. They’re just like we need a different way because this isn’t working. So that also involves, let’s embrace [and] learn about a different religion and different gods. So it really became just a whole way of thinking about identity and purpose.

Bhatt: You also mentioned the term “Black Power” in this book [and it] went through a lot of debate and conflict when it was first introduced by SNCC chairman Stokely Carmichael. How has that term “Black Power” evolved over the years?

Holley: Black Power movement really started Stokely Carmichael, who popularized the term as a way of advocating for self-determination. It really came out of the civil rights movement, which, like I said, they were sort of becoming disillusioned with the incrementalism of that. And they felt like, yeah, voting rights and everything…sitting at an integrated lunch counter is all fine and well, but we really need political power, we need economic power. So that’s kind of really what it means. Like Black Power is political and economic power, self-determination. And that’s where the Black Panther Party really comes out of. The Black Power movement was already rolling. The Black Panther Party said, “Well, OK, this is where we’re going now.” Huey Newton and Bobby Seale in Oakland said the Black Panther Party was for self defense, which is really just police accountability, serving your community any way that you can.

But yeah, Black Power, like you say, was debated a lot as to what it meant. Like, did it mean owning your own business? Did it mean just breaking off from the country and forming your own little independent nation? It was debated, but I think it was all about really just trying to get that sort of confidence back and folks were beaten down so much and just felt like there’s no progress being made. People were really just trying to think about, how can we have a little more self-determination and just self-empowerment?

Bhatt: We know the Lincoln Detox Center, which came in 1970 in the Bronx, and we also see Mutulu Shakur introduce acupuncture as a cure towards addiction. How did that all fit in with the Black Revolution Movement?

Holley: If you’re not familiar with Mutulu, who just passed away this last July, he was Tupac’s stepfather, he was Afeni’s second husband, and he discovered acupuncture. This was back in the early seventies when acupuncture really wasn’t as widely known as it is now. But he happened upon some newspaper article that was talking about what they were doing in China to help people that were withdrawing from opium withdrawal symptoms and using like ear pressure and little needles in the ear. And he’s like, “Well, people in the South Bronx are dying from heroin, maybe we could try this in there.”

So he just taught himself. He read some books. He and the Lincoln Detox Center at the Lincoln Hospital in the South Bronx really taught themselves acupuncture. I mean, then they brought in some people who taught them a little more [about] how to do it and how to administer it. And then they went on to teach other people how to do it and it took off. People were lining up down the street for this treatment. So for them, for folks like Mutulu Shakur, this is part of Black liberation because it is health care, it’s community health care, often free, cheap. It’s just addressing an urgent need, an immediate need. Seeing, like our folks are dying, or just being just wiped away and no one’s here to help us. So we have to help ourselves, we have to help each other.

So they just sort of took that initiative and said, well, we’re not gonna wait to go through all the red tape and everything that we have to do. They weren’t licensed. Mutulu eventually did become a doctor of acupuncture. But that was even a sort of weird roundabout way. He had to go to California to get licensed and then come back to New York. So he was licensed in California, but not New York. But he’s just like, “Well, at least I’m licensed.”

Then opening an acupuncture school to teach others, he didn’t have any permission to open the school, but he was just like, “Well, this is what we need…” And the Shakur family really, that’s kind of like how they just operated with everything. It’s just they saw immediate need and urgent need. How could we serve our people? And they just did it. They’re just like, “Well, let’s just feed hungry people, hungry school children.”We had to organize tenants who are being exploited by landlords. Just things like if you need legal service, you need legal aid. Like that’s what Afeni was doing. It was just all these little things that each Shakur really found their passion and things that they were good at and dived in.

Bhatt: Assata Shakur was also very passionate. Many Americans are familiar with her name. She remains on the FBI’s Most Wanted list, but she was an enigma, basically, her portrayal was manufactured by the police. You had a lot of media inventions. Could you describe her personality to us?

Holley: Unfortunately, I haven’t met her personally. So everything I learned about Assata came second hand. People who knew her and people who have worked with her, people who helped her escape from prison. And everybody and everything I learned about her, was that she became [the] Assata that we know after years of the trials that she was facing because she was being dragged to trial after trial for various alleged crimes - bank robbery, ambush of police officers. But she would be acquitted of charge after charge.

Then she was writing because people really didn’t know who she was. The media, police sort of built up this sort of larger-than-life character around Assata. So she felt the need to really speak for herself and to sort of say, this is who I am, is what I’m about because everybody is sort of portraying me in different ways. So I need to let folks know who I am and what they’re doing to me. So she was writing letters, just getting the word out and sort of spreading the word about who she was about, about who the Black Liberation Army was, which is what she was mostly affiliated with. She was a Black Panther Party member for a short time before joining the BLA [Black Liberation Army] which was a much more clandestine militant underground organization.

That’s really what she talks about the most, especially in her autobiography, which sort of made her more famous because she wrote that after she’d already escaped from prison, she was exiled in Cuba. The autobiography [was] a really important book and it’s really because she had time to really think about what was happening. She had a little perspective after being away from it.

But yeah, like you say, she was an enigma for most of the early-seventies, mid-seventies. And not really until the “cause celeb” sort of grew around her, people really rallied to her defense. And that’s when she was like, “Well, I need to speak for myself. I need to sort of define who I am for myself because the police are doing it for me, but it’s not accurate.”

Bhatt: In her words, she said, “Until every Black person is free, the Black Liberation Army still exists.” What does that revolutionary force look like today?

Holley: It’s hard to say. I mean, because what folks were doing and what they were fighting against in the sixties and seventies, like I said at the beginning, there’s similarity, but we have our own things today that are separate. We have our own ways of doing things as we should. The world is different, social media is just…we have different ways of addressing the things that we’re facing in society. And so to say, as she wrote, “The Black Liberation Army will always exist,” I don’t know if I agree with her. I mean, I think she was writing from a place that really felt like she believed that that might have happened.

But during the eighties, when she was writing this, her autobiography, the movement was really sort of falling apart and it already sort of started falling apart in the seventies and struggled to find its footing. And I think today, sometimes we often look to the past for, I don’t know, instruction or inspiration, which is good to look at what the folks were doing back then. But we also really have to keep in mind that we are fighting our own battles and we’re fighting different things today.

So it’s good to learn, take lessons from what the BLA did, from what Assata did, from what they all were doing in the sixties and seventies. But also just apply that to what we’re doing now, rather than use them as like, you have to emulate and copy what they’re doing. Just take what they did as inspiration, but also caution, because there’s a lot of mistakes that they made. They were young and impressionable, they didn’t really have much, there was no instruction manual to a revolution. So I think every generation just improves on the last movement or the last people. We learn from their mistakes.

Maybe, until Black people in America are on equal footing and the same equal rights as everybody else in this country, there will always be a fight for Black liberation, always be a fight for liberation. But it’s gonna look differently.

Bhatt: Let’s talk about Tupac.

Holley: Tupac, yeah.

Bhatt: To be Afeni’s son, to be tagged as the Black Prince of Revolution, I think for Tupac that would… like you’re dealing with this heavy weight of expectations. Isn’t it a lot of pressure for a young child at that point in time?

Holley: Yeah, I’d say so. He was raised with, like I said, the movement itself, or the elders, the veterans, people who had survived. A lot of them were incarcerated doing long bids and some of them had been killed by law enforcement. A lot of them were struggling with drug addiction, like Tupac’s mother. Tupac had the expectation, he had the burden, of feeling like all these people were expecting him to take up the mantle and talk to the new generation, get them active again, get them involved. And that’s what he thought of himself. That’s really what he even started to get into entertainment for. Like when started rapping, a lot of his rhymes, a lot of his songs were about the Panthers, about police oppression, about harassment, because he felt like that’s how we could reach people the best. That’s how we could reach his peers. That’s how we reach just the average folks on the street, using hip-hop, so it wasn’t like a contradiction for him.

He was chairman, for a brief time, of the New Afrikan Panthers, which was this organization that was like a youth organization that sort of picked up where the Black liberation movement had fallen off. So he was gonna be the chairman, he was gonna do all that work. But then he got a little bit of success as a rapper. So he said, I can better reach more people with music. And that’s why he got into it. I mean, he felt like he had a burden of responsibility but at the same time, and I’ve talked about this before, he had a lot of trauma from everything that happens in the book, everything that he witnessed or that his parents witnessed or survived. He grew up with this trauma, the whole family did.

And so he’s now like an international celebrity. He’s got money, he’s got fame. He’s in movies. He was a young man. He’s like 19, 20, when he first got started and he never really addressed what it felt like to be a Shakur. I mean, because that was a heavy thing. He was born and raised a Shakur, and to be born and raised a Shakur, to have that name, you’re already kind of a target for law enforcement, for institutional forces, which he carried with him his whole life. I mean, he was a target. It was like this thing where he just wanted to honor his family and the things that they had done. But he also loved to party and he’s a young man, and sometimes he just got knocked around. He couldn’t really just stay focused. He would just get knocked around a lot, which is understandable, but eventually it kind of got the better of him.

Bhatt: And keeping his music in mind, what role did his work play in the whole liberation movement? And how did he face acts of censorship?

Holley: He ran into trouble a lot with the police. I mean, there’s a whole list of things. Like he was always getting in trouble - sometimes it was justified, sometimes it was not justified. But a lot of the times, his lyrics, when you look at especially his first couple of records, sprinkled throughout and interviews, he didn’t shy away from calling out crooked police officers, crooked judges, income inequality…things that the community was facing at the time, he didn’t shy away from it.

And I think he attracted a lot of heat because of it, because he was very outspoken. I mean, not a lot of folks were doing it. There’s people, other entertainers, like Public Enemy, Ice Cube, who had that sort of… but Tupac lived that life. I mean, he was out there calling out police officers to their face, mouthing off. But when he actually had a quiet moment, and you can see in a lot of interviews, he would give it perspective and context, he’s not just a wild and out dude. He just thinks he’s invincible. He did, but when you got him to kind of quiet down and talk to an interviewer, then he would really explain like why he was doing this or what we’re up against, who he was, what his family expects of him.

He was surrounded by movement elders who tried to keep him focused. You know, sometimes you get called in on emergency meetings, like, “We gotta bring it back, we gotta bring in.” So like a lot of times throughout his life, up until the end of his life, people were still trying to keep him on track.

Bhatt: That takes me back to the whole “Thug Life” tattoo that you mentioned in the book. And that’s really interesting.

Holley: Yeah. “Thug Life.” When he got that tattoo - Tupac has [it] tattooed across his abdomen - he got it sort of on a whim. I mean, he didn’t really put a lot of thought into it. He really wanted to just portray himself as being hard because he was a sensitive theater kid, and he really wanted to just to try to fit in with this new crew that he’s running around with. And so he just was overcompensating a lot of times. He got “Thug Life,” thought that’d be hard.

But an old family friend, a movement veteran, Watani Tyehimba, brought him in. So at this point, Mutulu was still locked up and they had an emergency kind of meeting. They brought in Tupac to go talk to Mutulu at the federal penitentiary. And she was like, “What is this ‘Thug Life?’ You’re not a thug.” And Tupac was like, “I know, I know, I know,” and Mutulu was like, “Well, now you have this. So we have to figure it out. You have a lot of people [who] look up to you. So they’re gonna wanna know what ‘Thug Life’ is.”

So together, Mutulu and Tupac came up with a Code of Thug Life, and “Thug Life,” Tupac retroactively defined as, “The Hate U Give Little Infants F— Everyone.” Which like, how we treat children in society, has long-reaching effects on us, on society. And then they came up with the Code of Thug Life, which is basically just kind of similar to the Panthers’ Ten-Point Program. But for people in the nineties, who are living in the projects or whatever, just to abide by some sort of rules to keep us from killing each other all the time. So he used Thug Life to sort of become a platform like, a political platform in a sense.

Bhatt: Thank you. Finally, what does Tupac mean to you personally?

Holley: Wow. How much time do we have?

So I’m an old hip-hop fan. I was a fan of Tupac back when he was still alive in the nineties. I really didn’t think all that deeply about his music, about what he was talking about, until I got a little older and I was like, “Oh, this guy was deep.”

Then learning about his family and where he came out of, and what he was doing and was attempting to do with his life [during] his brief time here. He means a lot of things - really just embrace like how wild and crazy you are, but be willing to make mistakes and move on and admit your mistakes. I mean, Tupac made a lot of mistakes. He’s a very imperfect messenger. He made a lot of mistakes, he owned up to them.

I used to think he was contradictory, and the more I thought about it, the more I realized it doesn’t need to be a contradiction. You can have these two sides within you. You can be politically active, you can be committed to the movement, and you can also want to party and get drunk and smoke blunts and run around with your boys. And that’s who he was and both sides were equal in him. And I feel like some people want him to be one thing or the other. I think his brilliance was that he was both and he was both equally passionate about each side of his personality.

Bhatt: Thank you so much for these very knowledgeable 30 minutes, Santi. This is fantastic. I’m pretty sure we don’t have enough time in the world to cover the Shakurs and the Black Liberation Movement. But thank you.

Holley: Thank you so much.

Miller [narration]: That was OPB’s Prakruti Bhatt, in conversation with journalist Santi Elijah Holley at the 2023 Portland Book Festival. Holley’s new book is an “American Family: the Shakurs and the Nation.”

From Dennis Rodman’s hair color to Michael Jordan’s sneakers to Lebron James’ Tom Brown suits, The NBA has long been a place where players’ style off the courts is sometimes talked about as much as their style on the courts. Mitchell S. Jackson grew up in Portland and has since become a national literary name. His latest book is “Fly: The Big Book of Basketball Fashion.” It chronicles the relationship between basketball, fashion, politics and hip hop. OPB’s Paul Marshall spoke with Jackson at the 2023 Portland Book Festival.

Audience applauding…

Paul Marshall: Love the book. I’m not gonna lie. The pictures did all that work.

Mitchell Jackson: Yeah, well I hope so…

Marshall: I was like I say less, the pictures. But I am curious how it came about. You do have a basketball background, that’s fair to say…

Jackson: Yeah, yes.

Marshall: …and you do have an interest in fashion. So was this your idea? Did someone lobbed up to you? How do we get to “Fly?”

Jackson: I wish I could claim it as my idea. I never have any good ideas, but I know a good idea when I hear one, and that’s what happened. But I will say the very first piece of published journalism that I wrote was in the Portland Tribune in 2001 ‒ “Almost Famous” ‒ about some local guys who I thought should have went pro ‒ one of who was Orlando Williams, used to work for the Trailblazers, who was a guy I went to high school with. So all these years later, it does make sense that I would write about basketball and fashion, I think.

Marshall: It flows. I totally get it. But the title, “Fly”, like, there’s so many different ways you could go with that. I’m curious, was that a hard struggle to come up with the title, or was it…

Jackson: Man, I was in Savannah, Georgia. I was with my editor because I was doing a story on Clarence Thomas ‒ which is about as far away from “Fly” as you can get ‒ and he was like, ‘Man, the, the publishers want a title.’ And I was like, ‘Man, you wanna do it now? Like, what about Clarence?’

So we sat there, drinking tea and just kept going back and forth. And then I said, ‘well, you know, you gotta be fly.’ He was like ‘fly.’

I was like ‘fly.’

[Audience laughter]

I said, man, that’s it. Then he had the subtitle, ‘The Big Book of Basketball Fashion,’ because Esquire does ‘The Big Black Book’ of something like that. And I was resistant to ‘The Big Book of Basketball Fashion’, because I thought it was derivative. So I’m gonna claim ‘Fly.’ I’m gonna give him ‘The Big Book of Basketball Fashion.’

Marshall: One of the things I like about the book is it’s broken up by eras and not decades. When you were coming up and defining what is an era, what was the criteria you were looking for? What defined an era for you?

Jackson: The eras were marked by aesthetics. So I would take a look at a span of years in the league. I would say, ‘okay,’... I would either research or know who were the prominent players of that era. And then I would just look at as many photos as I could. And then I would say, ‘Where do I see a shift?’ Like a really explicit shift in the way that these players are dressing. And then I say, ‘OK, well, it looked like it happened in 60-something,’ I’ll say, ‘OK, well, what was happening in the culture in 1960 that might have informed the way that these players were dressing.’

And I would do that again and I would say, ‘Ok, well, if this was 60, where do I see another significant shift?’ I say, ‘Oh, well, this is 1980.’ Ok, well, what’s happened in 1980?’ And it got easier when I got into the eighties obviously because I was alive for some of that. But, but still it was finding the players, finding enough of them to be able to see if there were some shifts and then trying to investigate what might be their shifts. And sometimes it was something social, sometimes it was something political, sometimes it was something that was happening with the economy ‒ like the Reagan years ‒ but it was really fun looking back, especially at the players who I didn’t really have a familiarity with.

So if you go anything pre-1976, I didn’t really… like, you hear George Mikan, and like, I ain’t seen no George Mikan photos. So it was really interesting, and harder to find those photos as well.

Marshall: You did a lot of George Mikan drills when you played basketball though, right?

Jackson: Yeah.

Marshall: The flamboyance era is like… it’s really where we start to see a cut through in fashion or a distinctive style, and enter sixties and seventies and you see Walt Clyde Frazier, you see Willis Reed, you see even Pistol Pete, pretty fly for a white guy.

But talk about the flamboyance era and how people started to… that perception started to cut through and their image changed. That era seemed to be where it started.

Jackson: Yeah, I mean, I think you have to, in order to look at any era, you gotta look at the era that preceded it. And so for me, the era that comes before flamboyance is conformist. And so the NBA started in 1946, which we know was pre-civil rights. And so what happens if you are so lucky to be a Black person that is allowed into this league, that is really a white man’s league at the time. What does that mean for you in your community? How do you have to dress to be perceived as serious, right?

You know, I’ve said this, but I’ve never heard a white person being described as a credit to their race. But in the 1950s, Black people all the time were like, ‘oh, this guy is a credit to his race,’ right? Which also means you can discredit your race, right? By not dressing right, by being seen as fair weather. All these different things that can make you harm this kind of insidious, collective stereotyping.

And so I think that we get into the 1960s, thanks to what the Shakurs were doing, and King was doing, and all these people, and we get to legislation that makes us, at least on the books, we’re free. And I think that freedom shows up in the era of flamboyance, right? Like think about Blaxploitation and what was happening there. Like y’all, I don’t know if y’all watch some Blaxploitation movies, but they was big bell bottoms and shoes…, I mean, in your heel and all that. Yeah. So I mean, that’s freedom, or at least I guess it feels like freedom. And so I think that that era of flamboyance is really a response to what do we do when we feel free? When we finally receive a modicum of freedom?

Marshall: And those guys were heroes and it’s like, how does a hero look? How do they dress? You know, the Afro is a statement. Like that’s… it’s a statement.

Jackson: Man, I think if you are a basketball player, you got 82 game ‒ that if you don’t make the playoffs ‒ when you make the playoffs, you got 100 games… a hundred and I don’t know, something games. You got all those opportunities and every game is an opportunity for you to be a hero. Every single game, you can be a hero. What other profession could you be a hero a hundred and something times in a year? Really, in six months, right? Like, you write a book, you write the great novel, you took 10 years to write the novel ‒ unless you’re Jonathan ‒ and then you’re like, you got a year, maybe, that people are talking about it and then you gotta go back into your, you know… You didn’t get 175 times to be a hero in a year.

So I really do think that that’s important to how we view fashion and why these guys are so impactful because they have all of these opportunities. And not just that we see them walking down the tunnel. It’s that we see them walking down the tunnel to be heroic, right? Like, yeah, I can get fly, but I’m not no hero.

Marshall: We go from that to the Jordan era, and for better or for worse, there were a lot of things that were included. But one thing you note is, if you’re going to talk about the Jordan era, you have to talk about Reaganomics.

Jackson: Yes!

Marshall: They are tied together. You cannot separate them. Can you explain more about why they’re so,...

Jackson: I mean, there’s the famous Jordan quote, ‘Republicans buy Nikes, too.’ Or Republicans buy sneakers. I think that’s what he said. Which obviously didn’t hold up very well. Yeah, I think, in order to understand Reaganomics, you would have to understand the…

Okay, so what happened when Black people got their freedom in the 1970s? They gave us crack, right? And crack destroyed my community here for certain, and so many other depressed communities. So, we also get Willie Horton at that time. They’re trying to make the Black man, again, a danger like they did when they legalize cocaine, or make cocaine illegal, right? There were Black men raping women. So the same thing happened with this white backlash to Black freedom. And Reagan is really a part of that with his ‘make America great again.’ With his ‘how are we going to institute this restabilizing of our economy?’

So, all of these things are happening also at the same time that celebrity is hitting its apex, right? I don’t think that we can look at Michael Jordan without looking at Michael Jackson. And I don’t think that we’ve ever had had a bigger celebrity in the world than those two people. I think that that celebrity is also a celebrity that, it’s unlike the celebrity we have now, right? Where you can see what they’re doing every day, and they got Instagram and they’re making TikTok videos and like, we didn’t know what Mike was doing in between Thriller and Off the Wall. And I think all of those things, like the height of celebrity, the crack cocaine and the dehumanizing of Black people, was happening.

Then Michael Jordan takes the league in that era up to its apex, right? Magic Johnson and Larry Bird resuscitate the league. They have a drug problem in the 1970s. The league is faltering, their games are on tape delay. Magic and Bird, their rivalry ‒ Celtics and Lakers ‒ boosts the league. Now we watching games when they’re happening. And then Jordan takes the league to it’s apex. At Jordan’s height, he is the most famous person on the planet. Second only to Jesus.

Marshall: One thing also, too, is the money starts growing and the bags are getting bigger and the contracts are starting to get a little bit out there. And that impacts a lot of players because when you get money, it changes a lot of things. And during that era, we get the ‘Iverson effect.’ And that’s an era I started getting into basketball a little bit more. I remember that a little bit more fondly. But can you talk about AI’s impact? [Allen] Iverson’s, not… Just to be clear.

Jackson: I heard someone say this ‒ I wish I could claim it, but I’m not one of them dudes that’s gonna claim something that somebody else said ‒ but I heard it. Again, like a good idea, I knew it when I heard it. They said, ‘Iverson was the Tupac of basketball.’ And I agree with that, in the way that Iverson was a mythology before he ever stepped foot in the league. He gets in this big brawl when he’s in high school. First of all, he’s a legend in high school. He plays football ‒ as small as Iverson was, he was a great quarterback ‒ and basketball. So he’s already legendary. Then he gets into the brawl. He goes to jail. He needs a pardon to get out. He gets a pardon to get out. Like, you know you poppin’ when you get a pardon in high school to get out of jail, right? Then he goes and plays in Georgetown for the most famous Black coach in the history of college basketball. Can we agree on this?

Marshall: Ok, yes.

Jackson: There’s maybe some argument with Temple and all that, but really, it’s John Thompson. So all of that, then he’s the number one pick, right? So, if you look at Iverson, that mythology is running almost alongside Pac, and what’s happening in Pac’s life, and him getting in trouble. So they’re taking cues from each other. Pac is ‘71. Iverson and I are ‘75. So he’s not that much older than us. And certainly, you know, tattoos, the kind of resistance to authority. Like, that’s really Iverson. And I think again, in order to look at what we have now ‒ the Iverson effect ‒ we have to look at Jordan, which Jordan was corporate America. He’s a pitch man. He ain’t gonna say the wrong thing (unless it’s the sneaker thing), but Jordan really wasn’t caught out of pocket. He was not resisting David Stern’s mandates, Iverson is.

So, Iverson very quickly establishes himself as the future of the league, as the most iconic, and I don’t wanna say necessarily important, but the one that the league is patterning itself. All the young guns wanna be Iverson in some way. And so he’s also the antithesis of Michael Jordan. Iverson is getting his hair braided on the bench. He got lollipops. He wearing his shorts all big. Like, he’s everything Mike is not. And he’s also the future.

So, you gotta get a hold on that if you don’t want your league to look like a bunch of Iversons. And I think that that, coupled with the prevalence of hip hop… Hip hop is also hitting its apex. We got Jay Z’s ‘Big Pimpin’, releases in the early 2000s. All of these things, I think, and David Stern is a man of a certain era who has helped the league, ushered the league up to his apex. And he looking at this young dude like, ‘Man, if I get about five or six more Irversons in here…’ ‒ which he did ‒ ‘this could go south.’ And he recognized that and gave them a dress code.

Marshall: And that’s where it shifts, and there was a lot of pushback and it created a schism because you are telling Black and Brown people simply how to dress and, in another way, how to act. And with that dress code, how did the players react, and where did that land with some and some with others?

Jackson: So, when I hear people talk about Black liberation and Black self determination, they talk about them as if they are the same thing. But I actually think they’re different. Because if you say Black liberation, there is a liberator. And if you say ‘self determination,’ you’re saying, ‘no, I’m gonna do this no matter who is on the other side of this.’ And I think that you can look at the mandates of the dress code in terms of liberation, or in terms of self determination. I mean, either one can get us to here.

Marshall: I always felt that there was, like, a Kobe, who…

Jackson: He wanted to be Jordan! To be following that model.

Marshall: And you have those who, they acknowledge the dress code, but kind of tweaked as much of the margins as they could. And I wonder, now we’re post dress code, do we even have this IG walkway era if the dress code doesn’t… ? Because it swings again.

Jackson: I don’t think so. I don’t think we get to the dress code.

So again, David Stern, I don’t think he could have predicted this, but he really did set it in motion. I don’t think that we can get to the runway or the tunnel without the dress code mandates and the players trying to…

Remember, these guys are creatives. You can think of an athlete as someone who is physically gifted, but also it’s wizardry. It’s actually jazz on the court, right? If you practice, you do skills training, you practice the same move every time so that in the game you can maneuver in a way that it doesn’t feel that way, or you’re actually doing something that’s a riff on what you’ve done. So, it is actually art within. You look at Kyrie. Kyrie is art on the basketball court. And so if you give someone strictures and they’re artists, what are they going to do but figure out a way to be artful in that. And I think that’s what birthed these guys who are really ‒ fashion-forward guys who are really artists. Like they’re making themselves into visual art every time out in the tunnel.

Marshall: Is there an outfit that you feel best describes… I know one that you talked about is the night Lebron is gonna break the record. He’s about that. It’s gonna happen tonight.

Jackson: I think there are two. I’ll say that the Lebron outfit the night that he won, or he surpassed Kareem Abdul-Jabbar for the scoring title. I don’t know if y’all seen that, but go back and look. Man, that black suit was slick. He had all the diamond necklaces on. He had a pin that say, ‘stay present.’ His inseam was hitting him right there so you can see the socks and the shoes. Everything, it was beautiful and he knew that. I mean, when I saw that, I was like, ‘Oh, homie breaking a record tonight.’ Like, you can’t dress like that and not break the record, right?

[Audience laughter]

And he needed 30-something points. It wasn’t like he needed seven points to break. He needed a great game to break that record that night, and he put on that fit. It was like Superman’s outfit. Like, tonight’s the night.

And I think the other outfit I would say is Russell Westbrook ‒ I believe it might have been Paris, but I I’m not sure if it was New York or Paris Fashion Week ‒ in the Tom Brown outfit. And I say that because he was considered the most fashionable player, or one of the... I actually don’t think he’s the most fashionable player, but he was considered that. And he had on the skirt and I think that that was… For him to be in that position and to make that kind of a fashion statement ‒ which is really a cultural statement ‒ that that was a really important shift. Because then you get Jordan Clarkson doing it. Then you get Kyle Kuzma. But then you get the guys painting their nails, and you get a whole new crop of young dudes who are really pushing the boundaries against what masculinity looks like in the league. So, I think Westbrook really kind of set the tone for that to happen.

Marshall: There’s a term in the book, ‘accoutrement’, and you note that that’s an important distinction. If you have that in your gear, it puts you a step above. Like, there’s levels to it, but that puts you…

Jackson: Yes. I mean, I don’t know if you saw, but I think… I’m just going to venture to guess that you can go to the rest of the panels in Portland Book Festival and you won’t see nobody wear ring games like me and Elijah. That’s accoutrement. Now I’m a little biased, and I know this is the first one ‒ I’m making a very bold statement. But, you know, go ahead and look at some other panels and see what you see and bring it back to me. Let me know. That’s accoutrements.

And I do think it’s a different level. Because you can give a person the same suit, right? And then how are you going to distinguish your individuality if we all got to wear the same suit? It’s almost like the uniform, right? There’s some guys who wear the arm sleeve. Some some guys who wear something on their shin. Some guys like P.J. Tucker will wear a different pair of sneakers every time. There are different ways, but to me it’s all, ‘I’m an individual. How am I going to express my individuality inside of these strictures?’

Marshall: Everywhere you go, you rep Portland.

Jackson: To the fullest.

Marshall: Are there any Blazers ‒ past, present ‒ whose fashion that like… I know you’ve talked about Jeremy Grant. Are there any of that jump out to you?

Jackson: I would shout out to Jeremy Grant, who’s on the Blazers now. I think he’s one of the most fashionable players in the league. And you know, I never get my homie…

OK, so Damon Stoudamire is a good friend of mine and I think this was like… He was in the league, so he been out the league for maybe a decade now. Is that… am I right? I can’t remember who he was playing for. But he called me up one summer and he was like ‘Mitch, man, I need you to give me some fits. So I’m gonna send you some money.’ I was living in New York. He’s like, ‘Man, I’m gonna send you some money, man. Give me some summer fits.’

So, he sent me some money and I went and bought him a summer wardrobe, and took the pictures and sent them back and I had the stud fly. He wasn’t known for dressing, but I do think I’m gonna give him credit as a Blazer who actually has an outlook and a perspective on how he wants to be presented in the world.

I think also, not fashionable, but a POV, Rasheed Wallace. Which is, like, slouchy Blazer. You know, like, he gonna wear sweatpants, headband like he don’t give a….. Now, when you get to the Blazers that were around when I was young, I never saw Clyde. I guess he must have spent all his time in Lake Oswego. I’m gonna keep 100. Clyde never came to the gym when we was hooping. You know, Kevin Duckworth was there. I actually never saw TP either. I saw Jerome Kersey and I saw Kevin Duckworth and we would see Cliff Robinson would play. Those guys would come to the hood and play with us.

Drexler, nada. Terry Porter… never saw him. So, I don’t know what those dudes was wearing. But those guys were stars and they were here for a decade and we never saw them in the hood. Y’all take that and do what you will.

Marshall: I’m curious about your personal fashion. Has it evolved over the years? Are there eras that maybe like you rock a little bit more than you do now? Like, do you seek comfort? What are things that you look for now,

Jackson: Man, I’ve been jumping off the bridge a long time, man. I think you gotta cross the line to know where the line is. And I often cross the line. Every year I get out and I’m like, ‘Oh, Mitch, we shouldn’t have did this. Yeah, this wasn’t it, man.’

And you know my friends will be on my head about it. But I do think as an artist, I do treat fashion in the same way I think about a sentence. Like, have you ever wrote a sentence that’s a page long? Have you ever wrote a sentence that’s two pages long? Have you ever put so much onomatopoeia in something that it made your ear feel like it was blowing up? I’ve done all of that, and I will continue to do it, because I gotta know, not even necessarily where the boundaries are, where the opportunities are, how far I can really go. So you will see me, maybe this is today, maybe this is one of them... I’m gonna go home and, like, ah, ‘Mitch, I should have… maybe the proportions weren’t right on that.’ But also, I’m self critical. So by the time someone else says something to me, I already probably had that conversation to myself and it’s the same way with the work.

Marshall: Well, it looks like we are running up against the clock and I don’t want to get a shot clock violation. So we will go ahead and table it here. Mitchell S. Jackson, thank you for taking the time.

Jackson: All right, man. Thank you.

Dave Miller: That was the author Mitchell Jackson in conversation with OPB’s Paul Marshall from the 2023 Portland Book Festival.

Contact “Think Out Loud®”

If you’d like to comment on any of the topics in this show or suggest a topic of your own, please get in touch with us on Facebook, send an email to thinkoutloud@opb.org, or you can leave a voicemail for us at 503-293-1983. The call-in phone number during the noon hour is 888-665-5865.