When you think of Portland sports, you probably think of soccer and basketball. But Portland actually has a huge history with boxing.

In Portland’s historic Albina neighborhood, one boxing club produced some of the world’s top boxers and a national championship team: Knott Street Boxing Club.

The new book, “Fighting for Albina,” takes a closer look at Oregon’s historic connection to the sport.

OPB’s Paul Marshall spoke with author Aaron C. Jones about the boxing club and its lasting impact on the community.

The following transcript has been edited for clarity and length.

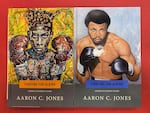

This photo has both versions of the Fighting for Albina book cover. The first image is a Basquiat-inspired boxing photo, and the second is Knott Street Boxer, Ray Lampkin.

Courtesy of Aaron C. Jones

Paul Marshall: What was the Albina neighborhood like when the Knott Street Boxing Club was at its peak? Can you paint us a picture of the neighborhood?

Aaron C. Jones: I lived in Southeast Portland and went to Cleveland High School. I would drive to Knott Street normally in the evenings, and then on weekends work out spar with guys.

It was somewhere between 80-90% of a Black neighborhood. Albina has been known as a boxing community. People know Knott Street. Everybody had somebody in their family history who boxed at Knott Street, because almost every boy in the neighborhood gave it a try. It was a part of growing up in the Knott Street community neighborhood.

They were making so many headlines. They were the trailblazers back in the ‘60s. They won the national championship and got even more headlines.

Marshall: The 1961 team that won the national championship. Can you tell us more about that team?

Jones: The Oregon Golden Gloves team was the third-ranked Golden Gloves in the Northwest.

Seattle was big. Tacoma was big. And then there was Portland. Portland would seldom win.

Starting in the early 1960s, all of a sudden these teams from Knott Street would send 10 boxers to Seattle, and six of them won championships out of the 10. And then they’d go to Tacoma, and five or six of the boxers would win. All of a sudden the limelight had gone off of Seattle, Tacoma and Canada, and it was Portland, Oregon, and basically just Knott Street. It was a huge switch.

This was a big sport because Muhammad Ali had won the prior year. The Amateur Athletic Union national championships were really big.

Most of the big teams sent 10 people, and seven of the 10 from the Oregon team were from Knott Street. They were mostly high school kids — juniors and seniors in high school.

One of the boxers, Johnny Howard, turned out to be a three-time national champion, and he did win the national championship in Pocatello, Idaho. He fought a young man who had just returned with Muhammad Ali from the Olympic Games in Rome, Jerry Armstrong. Armstrong had won his first three bouts in the Olympics and ended up taking fifth place.

Jerry Armstrong and Johnny Howard met up in the third round of the competition semifinals. Johnny Howard beat him hands down.

The seven boys from Knott Street were all fairly old-timers in the boxing ring in the sense that they had started when they were very young. They had already been boxing for 10 years, and their skill level showed up over in Pocatello.

Nine out of the 10 boxers won at least one match. Five of them made it into the finals, and a couple others won two matches. A total of 29 wins out of 35 matches that they had as a team. It was an outstanding and very high record. Twenty-nine points are far more than it normally took to win the national championship.

A very interesting kid was named Pete Gonzalez. Pete had only been boxing for six months at Knott Street. His family had moved into the area from Texas and he went to Knott Street. He just was one of these kids who would never take a backward step. He just was built to box, and he just moved forward and just kept boxing like crazy.

Related: Wall-to-wall soul: A Portland neighborhood’s bittersweet Black music history explored

Another kid on the Oregon team, Richard “Sweet” Sue, was also a featherweight just like Pete Gonzales. They both were in the same bracket in Pocatello, and had already fought each other six times in the amateurs. Each had won three bouts and they ended up in the finals against each other.

Pete Gonzales pulled out a close decision there. He went on almost immediately to the pros. He ended up being ranked number five in the world.

Richard “Sweet” Sue got drafted but didn’t have to go overseas. He got out of the military, and a few months later, he turned pro. He became the number one featherweight in the world.

Two hometown boys from Northeast Portland ended up in the top 10 in the world after competing against each other at the 1961 national AAU championships.

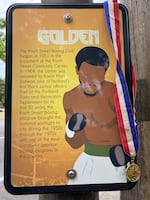

A Knott Street Boxing Club poster that recognizes the club's legacy in Portland's Albina neighborhood.

Courtesy of Aaron C. Jones

Marshall: In the book, you mentioned that there is a Muhammad Ali connection to the Knott Street Boxing Club. Can you explain those connections?

Jones: We had quite a few boxers who turned pro. Ray Lampkin would be a good example.

Paul Brown boxed over at Mount Scott, Oregon. He was a leading light heavyweight amateur back in the ‘80s. He did turn pro for a while, but he met up with Muhammad Ali and a lot of Muhammad Ali’s entourage.

He became a promoter in the Northwest and he got to know Muhammad Ali really well, and he invited him to all of his matches. It became a regular habit as often as he could get Muhammad Ali to come to Portland, and Pocatello, Boise and Coeur d’Alene in Idaho.

Related: Portland’s ‘Lightning Ray’ Lampkin reflects on boxing then and now

When Ali would come to Portland, they would normally rent a limo, and Paul would take Ray Lampkin and other boxers with him in the vehicle. They would pick up Muhammad Ali and his brother and they would hang out for a day or two, or however long Muhammad Ali was gonna be in town. This relationship went on for a long time. Ray Lampkin got to know him. They exchanged a lot of deep discussions about religion and all kinds of things.

The kids from Portland and guys who had boxed at Knott Street got to know Muhammad Ali, and they really loved him. You can tell from their reflections. They really appreciated the guy because he was a lot of fun to be around.

Related: Black-led advocacy group pushes to reclaim Portland’s former Albina Arts Center

Marshall: In the book, I noticed that there were a lot of fighters from different backgrounds, diverse backgrounds. Can you talk about some of the fighters that come from different backgrounds?

Jones: Six of the boys from Knott Street were Black. Pete was Mexican. Richard “Sweet” Sue, we’re not sure if he was Chinese, Korean or mixed perhaps. The family and I tossed that one around for quite a long time.

Two of the boys came from the Paiute Indian reservation near Burns, Oregon, and they had an amazing history behind them. Some of their relatives and ancestors had been Indian chiefs who had dealt with Oliver Howard and governors of Oregon.

They were outstanding boxers and they made it on the Oregon team, and they represented themselves very well at the national championships.

Marshall: You mentioned a lot of the notables earlier. Are there any other ones that kind of jump out to you?

Jones: Thad Spencer, one of the boys who grew up at Knott Street, was scheduled to fight Muhammad Ali. This fight was before Ali refused to go into the military and later had his license to box taken away. They never had the bout, but Thad Spencer was ranked number one in the world.

Amos “Big Train” Lincoln made it up to number five in the world. There were four of the Lincoln boys who were fighters, and three of them went pro and all three did very well. They all had winning records. Amos “Big Train” Lincoln fought Sonny Liston and Ken Norton. He fought Boone Kirkman up in Seattle.

He went to London, England, once and won a couple bouts over there against their top heavyweights.

The heavyweights probably outrank other weight categories coming out of Knott Street.

If you did a detailed study of who won what during that period of time, Knott Street would come out number one nationwide as the best amateur boxing team in America during that era.

Related: As membership declines, Portland churches see money and ministry in affordable housing

Marshall: What is the legacy of the Knott Street Boxing Club?

Jones: The legacy of the Knott Street Boxing Club is eternally linked to the legacy of Albina when it was predominantly a Black community. They chose to allow their boys to compete in a sport that a lot of communities didn’t favor.

For a boy to be involved in boxing for 10 years, which was common there: box when you were 10 and maybe retire when you’re 20, try for the Olympic team and try to win as many Golden Gloves tournaments, and go to as many national tournaments as you can.

The legacy is tied into the legacy of Albina. Fifty years from now, somebody will pick up the book and say, “Wow, look what they were doing here in Albina back in the 1950s and 1960s … that’s kind of interesting!” That’s why I wrote the book. It’s basically recording the legacy of the Albina community and its boxing team.