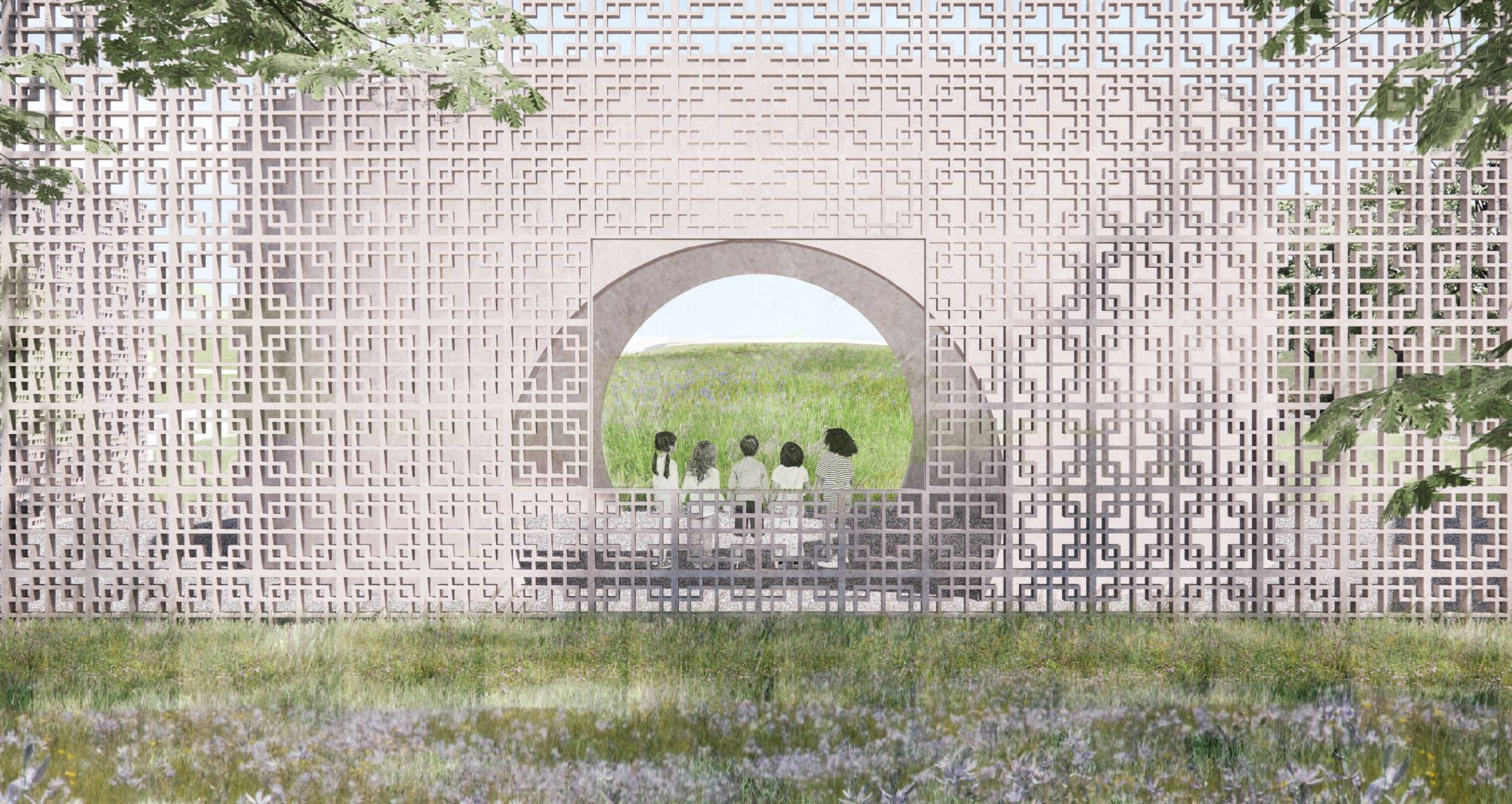

Metro has presented two design options for a memorial to be constructed by 2026 to honor people who were buried at Block 14 of the Lone Fir Cemetery in Portland. This artist rendering provided by Metro shows a panel from one of the designs featuring a moon gate, a circular opening or passageway in a garden wall found in traditional Chinese architecture.

Courtesy Knot Studio/Allied Works Architecture

Lone Fir Cemetery is one of the oldest continuously operating cemeteries in Portland. It also serves as a reminder of the often-forgotten history of Chinese immigrants who first arrived in Oregon in the mid-1800s, working as miners, merchants and general laborers. From the late 1800s to the 1920s, at least 2,800 Chinese immigrants were buried in a section of the cemetery known as Block 14.

Hannah Erickson, a communications specialist at Metro Parks and Nature, said historical records don’t shed light on how the southwestern corner of Lone Fir became a burial site for Portland’s Chinese community. They do, however, help dispel some of the rumors about its origins.

“There’s a lot of rumors and legends about how it came to be: that it was owned by a railroad company and that they were burying their Chinese employees there. That turned out not to be the case when we dug into the research,” she said.

The Oregon Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association in Portland, which still exists today, used ledgers to record the names of people who were buried at Block 14. But those gravesites were never intended to be a final resting place. Erickson said that “after a period of time, often many years,” the bones would be dug up, cleaned and placed in a metal box with the deceased person’s name and home village indicated on it, for repatriation and reburial in ancestral plots.

This photo from the early 1900s shows offerings left at an altar that once stood at Block 14, a section of the Lone Fir Cemetery in Portland designated for the burial of Chinese immigrants from the late 1800s to the 1920s.

Oregon Historical Society

Many people — including members of Portland’s Chinese American community — are unaware of the history of Block 14. Helen Ying, president of the Lone Fir Cemetery Foundation, grew up in Portland after emigrating with her family from China in the 1960s. She didn’t learn about Block 14 until her husband told her about it decades later, around 2004 or 2005.

“I think this is a prime example of the buried history — literally,” Ying said. “The last period [of burials] was probably like 1927, 1928 … so think about the time of what the society was like for the people living here. And the Oregon Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association was founded like other similar organizations around the country because there is nobody looking after them, right? And so they had to turn to each other because of the discrimination that was going on.”

By the late 1940s, Multnomah County officials claimed that all remains at Block 14 had been repatriated. But they hadn’t, according to an archaeological survey commissioned by the county in 2005 which found evidence of human remains at the site.

“We’re very limited in what we’re allowed to talk about when it comes to archaeological findings,” Erickson said. “However, we do know from those ledgers and from other research that has been done that there are probably still bodies in this site.”

Today, Block 14 is a bare field with no permanent reminder of its history or significance to the Chinese American community. But Metro, the regional government agency which owns Lone Fir, is attempting to change that by using a voter-approved parks bond to build a memorial to honor the memory of people buried at Block 14.

Metro has unveiled two design concepts for the creation of a memorial at the historic burial site, in addition to holding meetings last month with community members and the public online and in person at Lone Fir. Metro has also launched an online survey that is open until Nov. 28 to gather public input on the designs.

The two design concepts for the memorial are called “The Hill” and “The Grove.” The Hill envisions constructing a series of nested rooms at the foot of a hill built at the site. It also features moon gates, an element of traditional Chinese architecture, which open onto a garden path visitors walk along to a monument made of limestone that is inscribed with the names of people buried at Block 14.

The Grove is organized around a stand of gingko trees, which are important in Chinese culture as symbols of hope, memory and resilience. Interconnecting pathways lead visitors under a leafy canopy to a spot where an altar for making offerings once stood at Block 14.

The Grove, seen in this artist rendering, is one of the two design concepts for a memorial at Block 14. It includes an entryway of walls made of traditional Chinese celadon tiles with nested windows opening onto the historic burial site.

Knot Studio/Allied Works Architecture

“When Metro finally had the funding designated for this project, they put out the request for proposal and the Lone Fir Foundation wanted to make sure that we had a voice in helping to choose the designers, and it was like the stars aligned for us,” Ying said. “First of all, Michael Yun, who is the lead designer in this project, he’s Chinese American. He’s from Detroit where Vincent Chin was killed … so he understands the impact of discrimination, the impact of being marginalized.” Vincent Chin was a Chinese American young man who was the victim of a fatal hate crime more than 40 years ago when two white auto workers beat him to death.

Whatever design is ultimately chosen will serve to also honor another segment of the population that was similarly marginalized and dehumanized a century ago. Nearly 200 former patients from the Oregon Hospital for the Insane, the state’s first psychiatric hospital, are buried at Lone Fir — many in unmarked graves.

“We can tell the history of the Chinese and Chinese American people who were buried in Block 14, and we can tell the history of the OHI patients and the history of other marginalized communities because we are aware that with a cemetery as old and as complicated as Lone Fir Cemetery, we are likely to uncover more stories going forward,” Erickson said.

Metro expects the memorial at Block 14 to be completed in 2026. When it opens, Ying hopes it will allow visitors to not only confront a painful chapter of history but to also imagine a future strengthened by illuminating that history at last.

“It’s to honor and pay respect to those who are still buried there, and those who have been buried there and had gone unnoticed,” she said. “And then to be informed of how we could act to make our future even better as a whole, as a people of this country.”

Helen Ying and Hannah Erickson spoke to “Think Out Loud” host Dave Miller. Click play to listen to the full conversation: