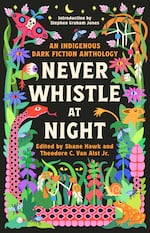

Spooky season might be winding down, but the nights are still long and dark. A new groundbreaking dark fiction anthology aims to illuminate a perspective on horror we may not hear often.

“Never Whistle at Night” is a collection of short stories by Indigenous writers. The co-editor, Theodore Van Alst Jr., is a member of Mackinac Bands of Chippewa and Ottawa Indians, and also the chair of Indigenous Nations Studies at Portland State University. He joined OPB’s “Weekend Edition” host, Lillian Karabaic, to talk about the book, which has spent eight weeks straight on the indie bestsellers list and is going into its 10th printing.

"For folks who have lost, whether it's language or homelands, whatever it happens to be, there's all this, the crude sort of trauma and horror and dark fiction that gives you an arena in which to talk about those things, right?" Theodore Van Alst Jr. co-edited the new anthology of Indigenous dark fiction "Never Whistle At Night."

Courtesy of Amie Van Alst

The following transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

Lillian Karabaic: I love the story of how this book came to be because I feel like it was Twitter for a force for good. So you’re a professor, you’re a novelist, you’ve got a lot of things going on. How did you end up, with your co-editor Shane Hawk, deciding to actually put the time and energy into making this anthology happen?

Theodore Van Alst Jr.: I wanted to do this thing for a while, and had a little folder and a file like you do on your desktop going for these stories.

But one day, one of our readers for this, Bear Lee, put up just a tweet and was like “When are we going to get an Indigenous dark fiction collection? When are we going to get some Indigenous horror collections out there?” So I was like, “okay.” I think I saw it and I was like, “Hey, Shane, what do you think?”

And so we just started talking and then we were like, “maybe we could do this.” Maybe we could do a Kickstarter, but it’s important. We want to get this done. And we talked to Gabino Iglesias and other people, like real powerhouses on the indie scene. How do we get this thing done? And we just started, “okay, well let’s put out a call and see what we get.” And we started asking around for stories. And I know a lot of folks from teaching Native American literature, but we really wanted an open call. So it’s half and half. It’s half new open-call writers and then half established writers. And that was really important. But once we put that out, it was like binging — bing, bing, bing. I’m in, I’m in, I’m in, I’m in. And then it just boom. It was just blazed across Twitter like wild.

Related: Theodore Van Alst’s latest book “Sacred City”

Karabaic: So you said it was really important to make sure you had an open call in there. Why was that important?

Van Alst Jr.: Because there’s so little representation of Native American folks in publishing — it’s less than 1%. And there are some established names and there are some go-to names, but that’s kind of an American thing. They always kind of want one person that they can go to. They always just want one go-to person for this niche group or this marginalized group of folks. And I’m like, “there are way too many voices for this.” There are just so many stories and needs for those stories to get out there that I thought, “let’s do this open call, and let’s hear some new voices. Let’s get some exposure.” If this is our shot to get it out there, let’s get the boat lifted up, and let’s get the tide moving. And man, we just got great stories from everybody.

Karabaic: Yeah, there’s one thing that struck me how much of a diversity of different types of stories there are in this. It’s all kind of in the genre of dark fiction and they all kind of have Native American themes woven through, but they had very different perspectives as far as the tribes, city versus rural… How did you end up deciding what to put in the anthology?

Van Alst Jr.: Yeah, it was important that we had this really broad representation in the stories from Indian country, which is the most diverse place that I can think of. And so you have hundreds and hundreds of tribes and traditions, languages and all of these things. How do we try to represent this in this small book? And the book isn’t this big. When we started out, we’re like, “hey, how about one more? Hey, how about one more?” So we were able to get these stories in there, and for me, it was important. If you look even geographically, we start with “Kushtuka” up north, and then we sort of move our way down and then we go around again and we end up back north at the end with Waubgeshig Rice. So we have this sort of, “let’s take a trip around and see what this looks like.”

But it was really important — two things. One, it’s an Indigenous dark fiction anthology. It’s not an ethnography. And the other thing is that it’s just dark fiction. It’s not necessarily horror. It’s not necessarily crime. And that’s not just for me because I like to write crime and horror together. But we wanted to say to people, “okay, here’s this broad subject. Just give us your best work.” That’s really what we wanted — giving us a story that you’re really excited about.

"Never Whistle at Night" is a groundbreaking anthology of dark fiction centered around Indigenous perspectives.

Courtesy of Penguin Random House

Karabaic: One thing that I really noticed was that a few stories in the anthology weaved together the stresses and fears of modern life with this historical trauma that a lot of Indigenous communities experience. Can you talk about the intersection and how you weave those lines together in picking stories?

Van Alst Jr.: Yeah. I think it’s important that it’s not just “we’ve survived,” but it’s also like “we thrive, we endure.” People are going on about their lives, but there is this big weight in the back. How does this manifest? Does it make for horrific situations? Does it make monsters? Does it make people into monsters? How does that look play out in what we call contemporary life? We’re talking about post-contact or whatever we’re calling about. We’re talking about centuries of just this apocalyptic nature for folks who have lost, whether it’s language or homelands, whatever it happens to be. There’s all this accrued sort of trauma, and how do you maintain, on a daily basis, a life in the face of those things? And so I think the dark fiction gives you an arena to talk about those things without necessarily the consequences you might experience in the physical world, but what does that look like? Does the monster get revenge fully? Is that what happened, or is there more to it? And how are you implicated in that thing? So it’s about creating this space to sort of work through those things, but also to show, “oh yeah, we’re not only here, we’re going to be here for a long time.” So that’s what we wanted to do.

Related: Indigenous writer explores what resilience means in Oregon

Karabaic: Yeah, it does feel like the stories never feel final even when they kind of have a conclusion. It felt like you just kept going in all of these stories. This book had quite a lot of success since it had been published, especially for something that I think a lot of publishers would’ve initially said is kind of niche. Something about this term that gets thrown around a lot in publishing is that these books aren’t marketable, or there’s not enough of an audience for something like a Indigenous dark fiction anthology. It’s had a lot of success. It’s nationally bestselling. What do you hope happens out of the success of “Never Whistle at Night” for other authors?

Van Alst Jr.: Well, I’m starting to see some successes for open-call authors in this book. I’m super excited. It’s sort of doing that thing already. We were really excited and enthusiastic that it was going to be published simultaneously on both sides of the border here and Canada. And so there’s a huge representation for First Nations authors. The audio book is all folks from up north. It’s all First Nations readers that did the audio book for us.

I think it’s about community. It’s about this large, large Native American community and what we are trying to do together, and how we can help boost each other, and how we can support each other and do those things. And so the book, I think, does that. I want to see everybody has great success out of this. And then I want to say, oops, you whistled at night volume two, volume three, on and on and on. Because people have already like, ‘okay, when’s the second volume coming out?’ And there are other writers. We didn’t get everybody in here. And there were a lot of great stories that we just couldn’t fit in here. So there’s definitely ample material for sequels for this here.

Karabaic: Thank you so much for coming in and talking with us. That was Theodore Van Alst Jr., the editor of the bestselling book, “Never Whistle at Night: an Indigenous Dark Fiction Anthology”. It’s available now at booksellers everywhere.

Van Alst Jr.: Thank you. Thanks for having me.