A shed sits over the spillway of the J.C. Boyle Dam. It contains a nursery roost for over 100 bats.

Kristian Foden-Vencil / OPB

An old shed stands at the bottom of the J.C. Boyle Dam near Klamath Falls. The building is unremarkable in just about every way — except that it’s home to a colony of bats.

“There’s a data gap on bats in the Pacific Northwest,” said Kaly Adkins, a conservation biologist with the Oregon Department of Fish & Wildlife.

That makes the shed valuable in a couple of bat-friendly ways.

First, the 1950s space is tiny, small enough that Adkins had to stoop to enter on one recent fall day. Bats like to hide away, so prefer these kinds of confined quarters.

Second, it has a corrugated metal roof, so the shed gets nice and warm in the summer, perfect for rearing bat pups.

Kaly Adkins, a conservation biologist with the Oregon Department of Fish & Wildlife, sets up antennas in the J.C. Boyle Dam shed to track bat movements. Sept. 27, 2023

Kristian Foden-Vencil / OPB

And most importantly, the shed stands right above the dam’s spillway, so there’s a constant flow of water underneath.

“There’s almost like an air conditioning factor of the cool water running underneath it,” Adkins said.

The shed has holes in the floor so that cool, moist air can flow in, and the bats can easily swoop out into the bug-laden evening.

While the shed makes a perfect bat roost, its actual purpose is to house machines that lift and lower water gates so that if the dam turbines need to be fixed, water can be diverted around the dam and out the spillway.

The spillway runs directly under the shed, keeping it moist and cool in the summer, and allowing bats to fly in and out. Sept. 27, 2023

Kristian Foden-Vencil / OPB

Next year the whole thing — the dam, the spillway and the shed — are all scheduled to be knocked down to allow salmon to once again swim up the full length of the Klamath River to spawn.

Like salmon, bats are also protected. So when they need to be moved — from a dam shed or someone’s home — the state advises the installation of bat boxes nearby to provide alternative habitat.

As a state biologist, Adkins said she hears a few basic questions again and again: What’s the best kind of bat box? Where should it be placed? And how big should it be?

“I went to the literature to try to understand and give a scientific explanation behind what I was recommending,” Adkins said, “and there just wasn’t a whole lot of information available.”

So she’s using the dam removal as an experiment to figure out what kinds of replacement bat boxes bats actually prefer, and what are the best locations.

“I thought: ‘Oh! This is a natural research question.’”

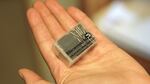

Microchip for tagging bats at Oregon Department of Fish & Wildlife office in Bend. Aug. 2, 2023

Kristian Foden-Vencil / OPB

The experiment’s first step started this summer and involved tracking the bats. She put up nets outside the shed to catch them. Then she injected a microchip under their skin, similar to the process veterinarians do with dogs, so that their movements can be tracked with antennas.

“We captured and tagged over 100 bats,” she said.

Adkins then put up a series of different bat boxes in different locations.

Kaly Adkins installed several different kinds of bat boxes to learn what bats prefer. Sept. 27, 2023

Kristian Foden-Vencil / OPB

The first is 100 yards from the old shed; the second is about a mile and a half away, next to a lake.

At each site she installed several large bat boxes, which she calls “bat condos.” They’re about the size of a carry-on suitcase and can hold a colony of 100 bats. She also installed several smaller cylindrical bat boxes, which mimic the shape of a dead tree — a bat’s natural habitat.

The boxes are on poles 10 feet off the ground, to protect them from predators such as skunks and racoons. And they’re all located in spots that Adkins thinks offer the right temperature and humidity.

“So we’re looking for good morning sunlight but then not a whole lot of midday or afternoon sunlight,” Akins said. “Because we want it to warm up quickly in the morning, but not bake.”

A bat is captured and tagged at the J.C. Boyle Dam in August 2023.

Courtesy of Kaly Adkins

While some people are scared of bats, they can be beneficial in a number of ways: They help keep insect populations, like mosquitos and pine bark beetles, under control. And in some areas, though not the Pacific Northwest, they even pollinate plants.

There’s a note of urgency to the bat box study because of a fungal disease known as White Nose Syndrome. It can cause mass bat die-offs

Bronwyn Hogan, who coordinates the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s response to the disease, says it’s gradually spreading west from the eastern United States and has been found in Washington and Idaho.

“So far the fungus has not been detected in Oregon,” Hogan said. “In California, the fungus has been detected at very low levels.”

The fungus grows on the noses of bats and wakes them out of hibernation early. They then spend scarce energy searching for insects that aren’t around.

Bat numbers are declining for a number of other reasons. Among them: habitat loss, the spread of wind farms, a decline in insect populations. And, bats are simply hard to study.

There’s little funding to pay for research. Unlike elk or salmon, people don’t hunt for bats, so there’s no hunting license fees to help fund research. Bats also carry diseases, which means scientists have to undergo a full series of vaccinations against afflictions like rabies to research them thoroughly. Bats are also very small, so attaching a sizable transmitter is difficult, although that is changing as technology improves.

Kaly Adkins, a conservation biologist with the Oregon Department of Fish & Wildlife, in her Bend office. Aug 2, 2023

Kristian Foden-Vencil / OPB

Adkins said it’s even been difficult to identify which kind of bat she’s studying. Traditionally, recording high frequency bat calls can help differentiate different bats.

But Adkins said she ran into problems.

“The calls that they’re making when they’re in your hand are not necessarily the calls, like ambient calls, that we classify off of,” she said. “We don’t have a specific classifier for a bat that’s being handled.”

Meanwhile, bats are not the only animal that the Klamath River Renewal Corporation is trying to protect as the dams come down. They’re working on everything from raptors to butterflies.

CEO Mark Bransom said crews have moved 500 sucker fish to Upper Klamath Lake and relocated dozens of Western Pond Turtles.

“We’ve been doing biological surveys for aquatic and terrestrial species for a number of years ahead of the project and will continue to monitor during and after the project,” he said.

J.C. Boyle Dam is scheduled to be removed along with three other dams along the Klamath River. Pictured on Sept. 27, 2023

Kristian Foden-Vencil / OPB

Back at J.C. Boyle Dam, the shed isn’t likely to be demolished until next fall. So Adkins is just waiting, in the knowledge that the colony could ignore her bat boxes altogether and disappear into the surrounding forest.

That’s just the nature of scientific experiment.