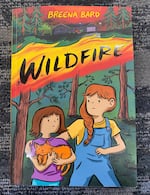

A copy of Breena Bard's "Wildfire" photographed on Sept. 11, 2023. The story follows Julianna, an eighth grader who’s forced to flee her home in rural Oregon and resettle in Portland following a wildfire.

Gemma DiCarlo / OPB

Breena Bard’s new graphic novel “Wildfire” focuses on Julianna, an eighth grader who’s forced to flee her home in rural Oregon and resettle in Portland following a wildfire. Julianna soon joins the conservation club at her new school, though she insists the fires that destroyed her home were caused by local boys with errant fireworks rather than climate change. The story follows Julianna as she processes her grief and learns to engage with climate issues in ways that make sense to her.

Bard joins us in studio to talk about the book and the many ways young people can take action on climate change.

Note: This transcript was computer generated and edited by a volunteer.

Dave Miller: This is Think Out Loud on OPB. I’m Dave Miller. We start today with the Portland graphic novelist Breena Bard. Her new novel is called “Wildfire”. It focuses on Julianna, an eighth grader in rural Oregon, who is forced to flee her home because of a forest fire and then resettle in Portland when her house burns down. The book is written for middle grade readers, but with themes of anxiety, grief, anger, and action, the topics are now sadly universal. Breena Bard, congratulations and welcome.

Breena Bard: Thank you so much for having me.

Miller: What made you want to write a book about climate change and wildfire in particular for a middle grade audience?

Bard: Yeah, well it wasn’t my plan initially. I was getting ready to write another mystery adventure story. That’s more of my wheelhouse normally and the year was 2020. If you remember that year, it was a difficult year and that kind of shifted my thinking to maybe talking about something a little bit more well, serious. And then we had the week, I think it was in August, with the wildfires where we had to stay indoors and tape the doors and windows because the air outside was just off the charts toxic.

Miller: And I still think of that as the worst time during a very bad time. That was still early on in the pandemic. And then there was tear gas in the air and then there was smoke. It was everything at once.

Bard: Yeah, it really felt like we were getting kicked while we were down. And it just so happened, I had a call in the middle of that week. We were also on high alert for a potential evacuation notice. So our family had our bags packed. We weren’t on evacuation notice but that was kind of where my head was at. I had a call with my editor during the middle of that week and I had pitched, like I said, another kind of adventure story to her and my editor, Andrea Colvin, said ‘that’s great. But what about something with a little more environmental focus?’ And she specifically suggested the wildfires. It just clicked in that moment like, yeah, that makes sense because I had already been kind of rethinking the stories I wanted to tell. And this was just inescapably in our lives at the time.So I sat down and the story just kind of tumbled out.

Miller: I gave a sentence or two, a version of the story in my intro. But can you describe what happens early on in the book?

Bard: It’s, I think, in the first 20 pages or so. It happens pretty quickly that Julianna leaves her 4-H Club where she’s happily helping animals and working the land. And she comes across one of her friends who’s playing with fireworks, even though there’s a burn band.

By the time she gets home there’s been a wildfire started and by page 20, I think, her family has evacuated. We don’t see the family’s home on fire at any point and we don’t see those dramatic moments play out in great depth.

Miller: We do see them sorting through that, with their parents saying ‘you got to pack your clothes, we’re leaving.’ We do see that briefly, right?

Bard: Right, it’s definitely an urgent scene and I wanted to really just emphasize the dread that surrounds an event like this. And then it’s over. Well, it’s not over. That particular event has passed and the rest of the story moves on to the aftermath and her grappling with that loss and the role that her friend played in starting the fire and just where she goes, moving forward from there.

Miller: When I read the book, it was impossible for me not to think about the Eagle Creek Fire of 2017, which was started by a teenager or a young person who apparently threw fireworks. The public has never learned the person’s name. But they were largely vilified in print and on social media. Why was that something that you wanted to fictionalize?

Bard: Yeah, when I said the story kind of came to me, that event definitely popped in my mind. And I think like most Northwesterners, there was a lot of anger. That something so foolish could cause so much destruction. And I think it was the first draft of my story that was much harsher treatment of that character. And really, he was kind of the punching bag to take all of the brunt of some of the lasting anger that I probably felt. And fortunately, my editor came in and after reading the first draft said, you know what? This character is a child. And this character is a person. And I think it’s important that we treat them with a little bit more grace. And I didn’t like hearing that at first because, well, nobody likes to hear the edits at first. But I think it really did push me to think about things like, should one moment, one mistake, be quite as costly for anyone? And I know that happens…

Miller: It sounds like you’re talking not just about what’s best for the story you’re writing, the graphic novel you’re writing. It seems like you’re talking more broadly about a shift in the way you’re thinking about what actually did happen in 2017. I mean, it seems like you’re talking about both of those things?

Bard: Yeah, there’s definitely a part of me, as angry as I was, I can’t help thinking about that person and the guilt that they must carry. And if their name does get out or if information does come out, and not just that particular person. Any wildfire that’s caused by human activity, that’s a rough road to go. And I didn’t want to center his story because it was Julianna’s story, always. But I do think that taking time to hear more about the fullness of his experience, hopefully brought a little balance there.

Miller: I mean, it did also occur to me that, even though for me there was this unmistakable echo of Eagle Creek, that was six years ago. And I can easily imagine that for, say, a 10-year old reader of your book, they have no knowledge of that, which really changed the way I thought about the book. And in that sense it’s kind of a made up way that the fire started. It’s not an echo of reality, right?

Bard: Right. And I think there are, unfortunately, going to be more instances like this, whether it’s a fire cracker or a campfire or who knows? But, yeah, I think they will become familiar with similar incidents.

Miller: And that gets to part of your character, Julianna’s, progression. It’s this complicated question of blame and complicity and communal responsibility when it comes to climate change. What were you interested in exploring there?

Bard: I think Julianna’s character begins in a place where it’s not that she’s not concerned for the environment but it doesn’t directly affect her. It doesn’t impact her in her day-to-day life, until suddenly it does. And I think I wanted to start from there, to maybe talk to those, including me. I didn’t feel personally affected until the week that, like I said, we were scared. We were ready to run. And I think it felt important for me to start her story there, to give readers a chance to see moving from, not apathy, but maybe just ‘it’s not my concern’ into ‘OK, it is my concern. And it’s the whole planet’s concern. It’s all of humanity’s concern.’ And there’s no more time to wait around. We need to get into action.

Miller: How did you choose the name Julianna for your main character?

Bard: I have no idea. It just popped into my head. I feel like it’s the cliche of a lot of authors to talk about the characters that are waiting in the wings, ready to jump into action.

Miller: And I have to ask because I was curious if it had anything to do with the Juliana of Juliana v US, which is this climate change lawsuit brought by 21 young people in Oregon, in Federal court eight years ago. And so when I heard Julianna and I heard climate change, I thought of that. But it’s just a coincidence?

Bard: Oh, interesting. Maybe that was just out there and that connection was meant to happen. I don’t know.

Miller: So in your character’s progression, she joins a conservation club in her high school, largely at first just because it’s a way to hang out with some new friends. In her new school, she doesn’t really know anybody. But, in the context of that club, she ends up learning a lot about climate change, about pollution, about conservation. And so there are some passages that deal with some of the basics of the science and of what’s happening. How did you think about the balance between that information she’s learning, and that readers take in, and then just propelling the narrative forward?

Bard: Yeah, that was a tricky balance to strike because there’s so much information. And one thing that I kept in mind is that if these are middle grade readers, they’re probably learning a lot of the same information in their science classes. So I didn’t feel like I needed to go too deep. But I did want to give the basics and it was helpful to have the club advisor, one of the teachers at the school, present the information hopefully in a way that didn’t feel too preachy, but more just ‘here’s our lesson today.’

Miller: A lot of the book is about the slow and uneven process of Julianna processing her grief, even just admitting what happened. She doesn’t tell her classmates and her friends in Portland that her house burned down, for a very long time, not to give anything away to the people listening. So this is about processing grief and trauma. What were you interested in exploring?

Bard: I think the thing about grief that’s been so interesting for me to learn about is just how nonlinear it is. And if you take that and apply it to a child, whose logic and reasoning tends to be more linear and more concrete, the confusion that would result. When you don’t have that clear path to ‘everything’s OK now.’ I think, hopefully, parents and teachers that read along can relate to some of that too.

Miller: It doesn’t seem like the parents…they’re very well meaning [and] kind people. But you didn’t create characters that do a great job, at the beginning, of helping her through her grief. They’re muddling through also. Why?

Bard: Well, as a parent, it seems important to me to represent just reality, like parents aren’t perfect. And I think to have examples of that and, like you said, they’re well meaning, they want the best for their daughters, but they’re doing it the best way they know how and things have changed so much, in what we know about grief and mental health in general. We do need to have room for conversations. And her parents are much more ‘let’s just move on.’

Miller: Right. What they basically say is that ‘we thought that by not really talking about this, by putting on brave faces ourselves, and not even showing that we are grieving or sad or angry or confused that we will help you by not showing you what we’re going through.’

Bard: Yeah, which I think would be my impulse too. As a parent, you want to protect your children. But I think being able to see that even these imperfect characters still do take action. Her parents are the ones that are going to the climate protests, before she’s even comfortable doing that. And they’re the ones that are very encouraging of her joining the conservation club, and always kind of suggesting activism as a way to process some of her grief. I think that’s helpful. That’s pretty good advice, in the mix. But it isn’t all she needs.

Miller: I don’t mean to say that they’re bad parents.

Bard: Oh no, no, of course.

Miller: What do you like about the age that you’re writing for, middle grade readers?

Bard: I think it’s such a fun age because they’re getting to the point where they really understand story and they really understand complex characters. And you can take things a little farther with them than early readers. And, you know, this isn’t a short book. It’s asking for a decent amount of attention and energy from young readers. But, yeah, there’s still an innocence, I guess. Maybe that’s not the right word but there’s still room for hope. Maybe the stories that I write for this age group, [who are] just getting started with their lives, they can take these stories into the rest of their lives. And that’s pretty, pretty amazing.

Miller: It is. But it’s so dispiriting even just because, I guess maybe you didn’t say this. But when you said that ‘they’re still capable of hope,’ I guess I just can’t help but think that the implication is that by high school or soon after, we lose that. Do you believe that?

Bard: I think it’s hard not to. I think we can learn from them though and we can hold on to that. The hope, I don’t think, happens by just sitting around and hoping for things to get better. I think it has to be hand in hand with taking action and whatever that looks like for any individual.

Miller: One of the big messages of the book, that you were saying earlier, is two things. One is that engagement and action and activism can look different for everyone. But the act of doing something can be beneficial for us all, especially if we’re talking about something like climate grief. Do you consider yourself an activist at this point?

Bard: I am a big introvert. So I think the part of Julianna’s character that feels overwhelmed by getting out in the crowd and being loud and doing a lot of that stuff, is difficult for me. So I haven’t labeled myself as an activist. But then one of my friends recently said, ‘yeah, but you did write a book that handles climate change and that’s a kind of activism on its own.’ And I think that’s what I want to lean into. Just like the characters in the book have to learn. We all have to find our own, really specific to us, our own way of engaging in activism. And I guess I maybe have found that.

Miller: Breena Bard, congratulations and thanks very much.

Bard: Thank you.

Miller: Breena Bard is a Portland cartoonist and graphic novelist. Her new novel is called “Wildfire.” She’ll be talking about the book at Powell’s on Saturday, September 30th.

Contact “Think Out Loud®”

If you’d like to comment on any of the topics in this show or suggest a topic of your own, please get in touch with us on Facebook, send an email to thinkoutloud@opb.org, or you can leave a voicemail for us at 503-293-1983. The call-in phone number during the noon hour is 888-665-5865.