On May 27, 1887, a gang of horse thieves gunned down more than 30 Chinese gold miners on the Snake River in Hells Canyon.

Chinese gold miner working on an Idaho River. The gold rush brought tens of thousands of Chinese people to America's West Coast.

Courtesy Historical Museum of St. Gertrude

Former Oregonian journalist R. Gregory Nokes spent years researching the events of 1887 for the book “Massacred for Gold.” He has called it the worst massacre of Chinese people by whites in the United States, “It was really an act of savage racial hatred. The main motive (of the killers) was to go and kill these Chinese.”

Chinese laborers in America

With the 1849 California Gold Rush, tens of thousands of Chinese laborers came to the American West Coast. They mined for gold, worked the railroads, and provided necessary services to newly developed communities.

Chinese people were among the earliest nonnative settlers in Portland. A photograph in the Oregon Historical Society Digital Collections from the 1850s shows the Hop Wo Laundry already established among the first buildings on Front Street.

Hop Wo Washing & Ironing was among the first businesses in early Portland, 1857.

Courtesy Oregon Historical Society Org Lot 1416_F02_002

According to historian and author Marie Rose Wong, at one time, Portland’s Chinatown was the largest in the country.

“When the Chinese started moving into Portland they could literally live anywhere a person was willing to rent them property, and that is exactly what they did. In terms of geography, it was much larger than San Francisco.”

A history of violence and racism

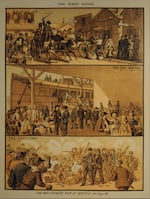

This West Shore Magazine illustration depicts the violence against Chinese residents in the 1880s.

Courtesy Oregon Historical Society

Oregon has a long history of exclusion based on race and nationality. In 1859, it was the only state to enter the Union with an Exclusion Clause in its constitution banning Black people. It also targeted future Chinese residents, “A Chinaman, not a resident of this State at the time of adoption of this Constitution, shall never hold any real estate or mining claim.”

Despite the law, thousands continued to immigrate to Oregon. In 1870, the census recorded over 3,000 Chinese people in the state. Ten years later, in 1880, the number jumped to almost 10,000.

Marcus Lee, board member of the Oregon Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association, says the increasing Chinese population faced hostility among white settlers. “The Chinese were being blamed for taking jobs away from white workers.”

Wong agreed. “The Chinese were looked at as scapegoats. They were really blamed for any kind of economic downfall that was taking place in the United States. You see the Chinese being chased out. And this story is duplicated in Washington, California and Oregon.”

A news article from the Jacksonville Sentinel in Southern Oregon described one incident in 1877: “a cabin occupied by a company of Chinese miners was set fire last evening by a party of armed men … who also began shooting at the cabin, which the Chinese were forced to abandon.”

In 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act barred Chinese laborers from entering the country. It became almost impossible for Chinese residents nationwide to become citizens or legally own property.

Some people thought the Exclusion Act would ease tension, but it didn’t, Wong said. “If you look at the incidents of violence post exclusion, it didn’t stop, in some ways it was even worse. So Chinatowns were burned out. Chinese were shot. They were hung. They were chased.”

Throughout the 1880s, Chinese immigrants watched their communities burned, attacked and sometimes destroyed by racist mobs. In 1885 in Tacoma, the town’s mayor, judge and city counselors took part in the violent removal of 300 Chinese residents, and the burning of two Chinatowns. At least two Chinese men died.

One of the worst events happened in Oregon.

Massacre at Deep Creek

The site of the 1887 massacre of over 30 Chinese miners working in the Deep Creek area of the Snake River in Hells Canyon, 2016.

Kami Horton / OPB

In the fall of 1886, a group of Chinese people set out from Lewiston, Idaho, up the Snake River and set up camp along a small stream known as Deep Creek. They mined the area for fine gold powder that may have netted them a few thousand dollars.

Then in May 1887, locals discovered bodies floating down the river. Other Chinese people in the area identified them as employees of the Sam Yup Company from San Francisco. The company offered a reward and hired a local investigator, while the Chinese consulate officially complained to the U.S. government.

Confessing to murder

Despite these efforts, the investigations didn’t turn up much until March of the following year, when Wallowa County rancher Frank Vaughan turned state’s evidence against six others.

According to a New York Times article from 1888, Vaughn’s statement read, “We entered into an agreement nearly a year ago to murder these Chinese miners for their gold dust…the men went down to the camp and opened fire on the Chinamen, killing them all.”

Nokes says the confession broke the case wide open. “We don’t know what happened, how he confessed, but he did confess, and a grand jury was held in which it implicated the other six members of the group.” Some of the accused white men were known horse thieves.

Without standing trial for the killings, three of the accused men fled the county.

“The others stayed on, were found innocent at the trial, and became ‘respectable’ in the county. Frank Vaughn served on the school board and the road commission, which suggests some respectability” said Nokes. “They were never held accountable for the crime.”

Remembering the victims

In 2012, Nokes and others held a ceremony to add a granite monument to the site engraved in three languages — English, Chinese and Nez Perce. The words on the memorial: “Chinese Massacre Cove — Site of the 1887 massacre of as many as 34 Chinese gold miners — No one was held accountable.”

Nokes says, “Of all the many things I’m proud of in my professional career, my involvement with that monument makes me the proudest.”

“Oregon Experience” — Behind the scenes

“Massacre at Hells Canyon” originally premiered in 2017. Oregon Experience crews spent several days in Eastern Oregon and Idaho the previous year. On a hot August day, we traveled up the Snake River by a sightseeing jet boat, were dropped off at the massacre site on Deep Creek, and spent several hours exploring the area.

OPB crew and gear dropped off for a day of videotaping on the Snake River in Hells Canyon, 2016.

William Ward / OPB

The river cutting through the canyon is breathtakingly beautiful, but the site also holds an eerie stillness. Many remnants of the Chinese gold miners remain. We saw the stone walls they had built, the dug out area used as a camp and cook site, and the monument placed in 2012 in their memory. It was easy to imagine the dozens of men that worked here, hoping for a bit of gold and a better life.

After the program aired, a Chinese-American group contacted OPB requesting a Chinese version of the documentary be made available. With the help of Chinese actors, we were able to provide a Mandarin language version of the program that is available online.