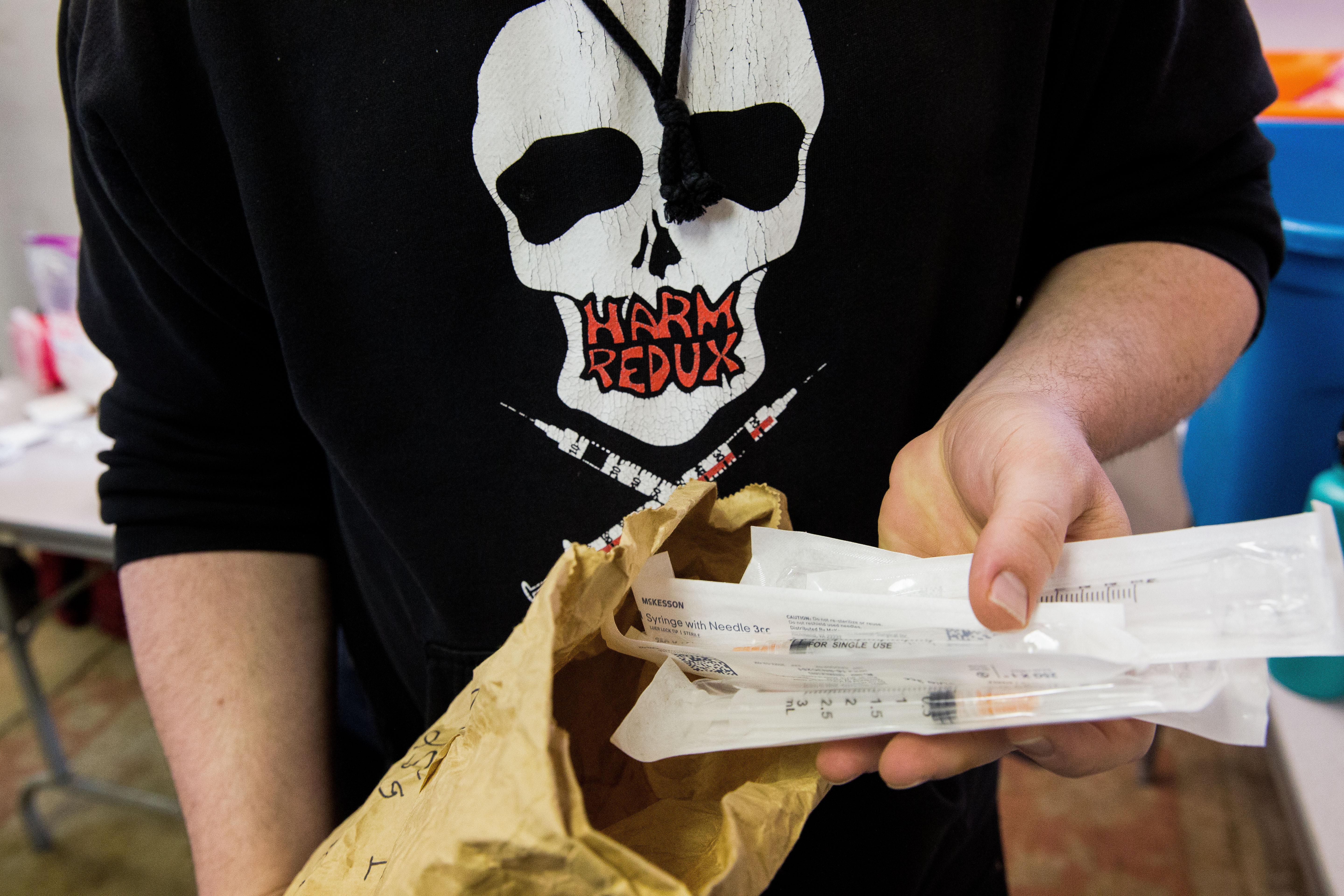

FILE - A volunteer with the Portland People's Outreach Project shows clean needles and other supplies offered to injection drug users in 2018.

Amelia Templeton / OPB

After a shambolic rollout, Oregon lawmakers say the state’s pioneering drug decriminalization measure needs an overhaul.

Democrats who control state government aren’t toying with the idea of reintroducing criminal penalties for low-level drug possession, something many GOP lawmakers have called for this year in response to rises in overdose deaths and property crime.

Rather, a bill that got its first hearing Tuesday evening would retool the process for how hundreds of millions of tax dollars allocated to Measure 110 find their way to addiction service providers around the state. A major change: granting the Oregon Health Authority a more muscular role in soliciting grant proposals, getting funds to providers and evaluating services — and potentially paying the OHA far more to do so than voters approved in 2020.

“It’s clear that in its first years, there were issues with Ballot Measure 110′s implementation,” said state Rep. Rob Nosse, D-Portland, who introduced the proposed changes after meeting with interested parties for months. “We owe it to Oregonians to make sure that the voters that passed Ballot Measure 110 are getting what they ask for.”

Passed with more than 58% of the vote, Measure 110 was sold as a way to rethink drug addiction, treating it as a health problem rather than a crime. The measure eliminated criminal penalties for possessing small amounts of illegal drugs. It still grants police the ability to issue violations akin to traffic tickets for possession, though few do.

Measure 110 steered the bulk of taxes the state gets from recreational cannabis toward expanding and bolstering addiction services throughout the state. To date, the measure has sent more than $150 million to organizations throughout Oregon. Advocates say it has already helped tens of thousands of people access services that can steer them toward treatment.

But the process for getting that money out has been plagued by delays. An Oversight and Accountability Council that, under Measure 110, is responsible for approving grants, found itself swamped by applications as it looked to set up service networks in every county. The Oregon Health Authority has acknowledged not giving the group the level of attention and staffing it needs to be successful.

The bill Nosse is floating would change that. Under an amendment introduced this week, House Bill 2513 would expand the OHA’s responsibilities under Measure 110, giving the agency authority to tackle administrative tasks currently assigned to the council, which is made up of many people who’ve been addicted to substances.

Nosse said the law, as initially implemented, didn’t offer enough structure or staff support.

“We treated it a little bit more like the Parent Teacher Association that’s running the school auction than we treated it like a government oversight body that really has responsibility for implementing a government program with a lot of money,” he said.

In exchange for its stepped-up responsibilities, the OHA would have no shortage of funding at its disposal. Voters approved administrative costs for Measure 110 that would total no more than 4% of the tax dollars allocated for services. As things sit today, that amounts to $10.5 million just to administer the measure.

But Nosse said the cap should be removed.

“I don’t think we should set an arbitrary 4% cap,” he said Tuesday. “I have no idea if that was enough, but what I do know is that it was covered well in the media that it wasn’t a great administrative process.”

Nosse’s proposal would also:

- Stagger terms of members of the Oversight and Accountability Council to ensure there is not massive turnover on the 22-member body all at once.

- Clarify that people with both mental health issues and an addiction qualify for services under Measure 110.

- Delay a performance audit by the secretary of state by a year to late 2025, to account for delays in distributing money to providers, and require that audit to look into the impact Measure 110 has had on overdose rates, as well as whether tickets currently handed out under the law are successful in steering people toward help. (Early numbers suggest they are not.)

- Authorize the Oregon Health Authority to pay for an ad campaign informing Oregonians about services offered under Measure 110.

Nosse’s bill is the second major legislative proposal for altering Measure 110 since it won approval, and has backing from service providers and their allies, who say the changes will allow Oregon to be more nimble as it expands addiction services.

“When you have a community-led process, you need to have really strong staffing,” said Tera Hurst, executive director of the Oregon Health Justice Recovery Alliance, which advocates for Measure 110′s approach. “This is intended to make sure the health authority does what they know how to do … but still optimize and ensure that the lived experience that this council has, which is huge, is being reflected in the services on the ground.”

The bill is likely to see criticism from Republican lawmakers, who do not believe it goes far enough to alter Measure 110′s impacts.

On Thursday, state Rep. Lily Morgan, R-Grants Pass, asked Nosse whether the kinds of programs Measure 110 is funding — which include harm reduction, housing and peer support services — could effectively get priority over expanded residential treatment and detox facilities that Morgan argued are needed more.

“I’m wondering if we put a bow in the hair before we had the haircut,” Morgan said. “It’s kind of one of those things of: which order do we do it in to make sure that we have the life saved before we have the support services?”

Nosse responded that there are also bills in process to pour more money into community mental health, residential treatment facilities, better pay for mental health workers, and more. Those bills might be competing for a relatively small pool of cash state budget writers say is available in the next two-year budget that begins in July, but Nosse suggested they have a chance.

“It’s not even April yet,” he said. “I would just say: Stay tuned.”