Fifty-one years ago, the largest crowd to ever witness a live indoor sporting event made its way to Portland’s Memorial Coliseum. The reason: the Oregon high school boys basketball championship game of March 25, 1972.

It was the first to feature a team of entirely African Americans players — from Portland’s Jefferson High School — versus an all white team — from Baker High School in Eastern Oregon.

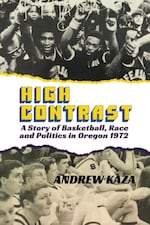

The book “High Contrast” takes a closer look at what the author calls “a battle for the soul of Oregon.”

OPB’s Paul Marshall spoke with author Andrew Kaza, about the game and its lasting impact on the state.

Andrew Kaza's book chronicles the 1972 Oregon Class AAA state championship basketball game between the Baker Bulldogs and the Jefferson Democrats.

Nestucca Spit Press

Paul Marshall: You write that the state championship game between Jefferson and Baker seemed to be a battle for the soul of Oregon. What exactly made this game so different?

Andrew Kaza: It was certainly a product of its time. High school sports was at its zenith in the state of Oregon at that point in time.

The [Portland] Trail Blazers were in their second year. They were pretty lousy. Not many people were going to watch them. The universities, Oregon and Oregon State, weren’t terribly good at basketball at the time. Arguably Portland State had the most entertaining team in the state.

High school basketball just had the state captivated at that point in every corner of the state. So if you went to a place like Klamath Falls down south where they had had a long run of strong performances, it was big down there, or in Medford, you go out to Eastern Oregon, where Baker had many years of success.

Then you come back to Portland and arguably some of the greatest players ever to play in the state of Oregon converged in 1972, including a near 7-footer from Benson High School named Richard Washington, who became an All-American at UCLA and played in the NBA. There were these extraordinary players from Jefferson.

On a basketball level, this particular tournament and this championship just had it all, which is why you had the biggest crowd in the history of the state of Oregon attending an indoor sporting event before the Blazers built their arena. This was the biggest sporting event in terms of attendance ever in the state of Oregon.

It was also about an all Black team playing for the state championship, which would be a first against a bunch of all white farm boys from Eastern Oregon. It seemed to notify what we call today, the urban rural divide. It was clearly a division in the state that people were coming to grips with.

Marshall: Can you set the scene for us? How many people were at the Memorial Coliseum that day?

Kaza: For the championship that night, there was a recorded attendance of 13,395. Although as I point out in the book, there could have been up to several hundred more who attended without a ticket because the Coliseum was fairly porous in terms of security. In those days it was not a difficult building to gatecrash necessarily.

I think you had a number ultimately that was pushing 14,000 people in the building. It was heaving at the seams and part of that was high school basketball. There was just a tremendous amount of interest for this game and it built up all week long.

A lot of people expected it was going to be Jefferson versus Benson for the state championship. They had played two games decided by two points or less during the regular season and they were ranked No. 1 and No. 2 all season long. But then Benson got upset on Thursday night in the quarterfinals which opened the door for another team to take on Jefferson. And ultimately, that was Baker

Marshall: The 1970s were a tumultuous time in the U.S. Can you talk about some of the tumult that played out in the city of Portland, especially in 1972?

Kaza: 1972 was a very interesting time. First of all, an issue that we’ve kind of largely forgotten was front and center in the country and that was busing.

It gripped the city of Portland just like it was gripping cities back East and down South. It was a debate that people were having and Portland kind of took an unusual angle on it.

The superintendent who later left without a lot of accolades tried on a few things, other places didn’t.

There was also a small group of Black Panthers in the city. There had been protests, not quite like what we saw in the last couple of years and there was nothing called Black Lives Matter back at that point in time. Portland certainly had its racial strife and that reflected in some of what went on with the teams.

For example, Jefferson’s home games during this season were all played in the afternoon. They were played on Tuesday afternoons rather than at night because it was deemed too dangerous to have games in the evening. There were concerns about so-called riots breaking out. So they had a home court disadvantage if you will. Some of the players pointed out that their second home game with Benson got moved to the Memorial Coliseum during the regular season.

You might say that was because there was so much interest in the game. There were almost 8,000 people who came to this game on a Tuesday afternoon and only 6,000 or so went to the Blazers game that night. As far as the Jefferson players were concerned, they had a home game taken away from them (even at the Coliseum).

There were also racial incidents if you went to a city like Astoria, where Jefferson played in the preseason. There was open racism on display.

These are some of the things that the Jeff guys had to overcome and, not just the other team on the basketball court for 32 minutes.

Marshall: Can you introduce us to some of the players from each team?

Kaza: In the case of Baker, it’s pretty simple. They have one real stud player who was not quite the Richard Washington element, but he certainly carried them in a lot of games. He was a 6-foot-8 pivot man by the name of Daryl Ross. Ross would go on to play college ball at Montana State. He had a pretty simple game but it suited Baker’s philosophy really well.

They had a couple other guys who could light it up, but they were all about efficiency and they played a very controlled kind of game. This was the other thing about the championship. It was a total contrast in styles.

Jefferson had a bunch of racehorses and they had guys that just could take it up and down the court and fly. They were quick and talented at several positions.

Their biggest player was a guy named Carl Bird who went on to play at University of California, Berkeley and his son, Jabari Bird, played in the NBA for a while as well and also at Cal.

They had a guy named Charles Channel who was the lifeblood of this team. He comes from a well-known family In Portland. His younger sister Lisa wound up becoming an All-American, one of the first female All-Americans from Oregon State for basketball. In the backcourt, a couple of guys who were real close during their high school years, Ray Leary and Tony Hopson. They were the best two guards in the state.

The fifth guy who was the only junior in the starting lineup, wound up having probably the biggest career of all post-Jefferson. That was Ron Cole who went on to play at the University of San Diego. He held several records there for a long time and then ended up playing for the Harlem Globetrotters for a number of years.

When that’s your fifth man and he goes on to play for the Harlem Globetrotters, that tells you what kind of talent Jefferson had across the board. They had a couple of really good players off the bench also. They were deep and you couldn’t just focus on one player.

Marshall: You also write in the book that at this time there was a shift going on in Baker City. Can you explain what happened?

Kaza: Like in a lot of Oregon, Baker was transitioning in that time both from the economy which had been based around timber and being a transportation hub for northeastern Oregon, to sort of a post-industrial economy.

That shift was starting to happen in the early ‘70s.

Politically, there was quite a shift going on. Strangely enough, the bastion of Democratic politics in Oregon back in 1970 was Eastern Oregon, not Western Oregon. Oregon had two Republican senators at the time and most of the congressional delegation was Republican. The two exceptions were Edith Green, who was the congresswoman from Portland and Al Ulman who was the congressman from Baker City and he was in Congress until 1980

The sort of politics in Eastern Oregon at that time were agrarian, but they were pretty strongly middle class, working class, Democratic politics.

You could almost see a foreshadowing with what was gonna happen eight years later with Reagan, with the politics at the time. In Baker, people began to get a little more conservative, concerned or fed up with what was going on with the country at large with the Vietnam War and protesters. There was kind of a shift underway going on at Baker.

Marshall: Former Portland Public School Superintendent Robert Blanchard had his Portland schools for the ‘70s plan. Can you explain what the plan was and how that impacted Jefferson?

Kaza: It impacted Jefferson in a huge way, probably more than any other school.

In the Portland school district, they were trying to wrestle with a couple of different issues. The busing issue being one of them, but mostly of course, the overriding issue was the disparity of performance with students at various schools in the district.

Although they didn’t really recognize it at the time, there was also going to be a big issue with declining enrollment throughout the ‘70s because the baby boomer era was peaking.

Jefferson in 1972 had an enrollment well over 1,000 and within a handful of years, it would be half of that. The district made a decision to turn Jefferson into a magnet school.

Jefferson became a magnet school for things like performing arts and people from all over the city started going there. Blanchard’s blueprint was to try to do a limited amount of busing in the city and kind of cover his backside with that without it being mandated.

Eventually they would end up closing a bunch of schools starting on his watch. Schools like Jackson and Washington ended up closing in the early ‘80s.

So the Portland School District kind of went into retreat. A lot of people think that his aims were not successful, to put it bluntly.

Marshall: Jefferson would go on to defeat Baker 59-52. After the game, what was the aftermath for each school? What path did it put Jefferson on? And where did Baker end up afterwards?

Kaza: Having talked to some of the Jefferson guys, one of the reflections they’ve had is that the game was a turning point for them in their lives. It wasn’t the greatest moment in their lives — that might have been when they were married, had kids or other things. They all recognize it as a huge turning point that spurred them on to greater things later on.

In the community, it was a huge deal in the Northeast Portland/Albina community when Jefferson won. They were treated for many months as kings in that community for bringing home the trophy. It was just a tremendous source of pride within the Black community in Portland.

In Baker, there was equal amounts of pride even though they had not won the championship.

A ton of their fans came over to watch the games in Portland and they came back with a new, renewed sense of pride in their community for having come so close.

Baker’s grown up a lot. One of the Baker players was a guy named Fred Warner who went on to become a mayor of Baker City and served on their council. He has a lot of perspective about it and he readily acknowledges that their history wasn’t so great and that maybe this game helped change at least a few attitudes. You put these guys on a basketball court and there was nothing but respect between the Baker and Jefferson players.

Marshall: Where does this game rank in Oregon sports history for you?

Kaza: I think it’s definitely in the top 10, maybe even in the top five.

When you think of significant events in the state of Oregon and achievements, the Blazers championship in 1977 probably ranks the highest of anything for most folks. You might put a couple of the Timbers (and Thorns) championships up there if you’re a soccer fan. Then you’re probably looking at things like Oregon winning the first NCAA (men’s basketball) championship in 1939 — that’s ancient history to most of us. Maybe a few of the football exploits of OSU or Oregon.

As a high school game, I think this particular game is completely unmatched. I do think in terms of overall sporting events in the history of the state, it’s got to be in your top 10 if you know about it and, if you know it well enough, then I put it in the top five.