Everywhere they look, Pacific Northwest scientists find teeny-tiny plastic pollution. Broken down particles are in our water, falling out of the air, in salmon, shellfish and in our own bodies. Scientists, environmental advocates and Democratic lawmakers in Olympia and Salem have seen enough to make them seek more regulations.

Professor Susanne Brander is a toxicologist at Oregon State University. Her lab at the Hatfield Marine Science Center in Newport offers a window into the ubiquity of microscopic bits of plastic in the environment and what that does to animals and fish.

"We're sampling everything and the kitchen sink these days to see if micro- and nanoplastics are accumulating," Brander said while scanning the inventory of the science center's walk-in freezer.

The shelves of the frigid cooler are chock-a-block with rockfish guts, squid, sea otter poop, shellfish, even human sewage – technically known as biosolids, which were sent to the lab from various wastewater treatment plants in the region. When lab techs examine the samples, they pretty much always find some traces of broken down plastic litter, or fibers, or tire particles.

Brander is also running experiments where she intentionally feeds artificial particles to small fish and mysid shrimp. Her team is seeing that ingestion of microplastics and microfibers leads to reduced growth, inability to absorb nutrition, cellular stress or changes in swimming behavior. As a scientist, Brander said she hesitates to be seen as an advocate for political action.

"But the science is there," Brander added. "We may not have all of the answers yet. We may not have a clear picture on what's happening with human health, for example, in terms of microplastic exposure. But there's enough data to support moving forward now rather than waiting."

This decaying plastic litter on the beach at Newport, Ore., is on its way to becoming microplastic pollution.

Tom Banse / NW News Network

"We could wait another couple decades, but are we really going to know that much more at that point?" Brander continued. "And we're going to see more damage occur in the meantime."

Brander co-authored an open letter signed by scientists from leading universities around the world urging swift agreement on a new United Nations treaty to reduce plastic pollution. Rather than acting swiftly though, the treaty negotiation involving 160 countries is proceeding at a snail's pace.

Oregon Democratic state Rep. David Gomberg said in an ideal world, Congress would also pass laws to reduce plastic pollution. Then the rules would be the same for everybody – not where we are now with states and cities legislating in piecemeal fashion.

"The products that we are buying and using here in Oregon don't all come from Oregon," Gomberg pointed out. "So, we can write all kinds of laws about what we do for products that we sell here, but sometimes that makes it more expensive for those products to reach the marketplace. And sometimes that means fewer of them will come into a state the size of Oregon."

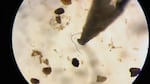

Microplastic fibers are less than 5mm and often show up a vivid color under the microscope.

Todd Sonflieth / OPB

That said, Gomberg and other West Coast lawmakers recognize it could be a long wait before the divided Congress does anything. So, the spotlight for anti-plastic campaigners returns to state capitals, where they've already registered wins.

"They have to start with some states that are working on this and we have to see those solutions work in those states," said Charlie Plybon, who lobbies for plastic pollution policies on behalf of the Surfrider Foundation in Oregon.

"As we advocate, we start to see other states falling in line. As more producers are having to operate in different states under different policies potentially, that drives some more interest for federal solutions that could create consistency for the entire nation," Plybon said.

Plybon and Gomberg spoke on the sidelines of a biannual meeting of the Pacific Northwest Consortium on Plastics in December, where West Coast microplastics researchers discussed their latest findings and spent half a day pondering how to convert science to public policy.

Plybon said he is pretty excited to see multiple efforts to reduce plastic pollution on deck in Salem this year. Democratic state Sen. Janeen Sollman had a passel of bills drafted to tackle everything from banning polystyrene foam takeout boxes and packing peanuts statewide beginning in 2025 to changing the health code to allow consumers to bring refillable containers to restaurants and grocers. Fellow Democratic state Sen. Deb Patterson just sponsored another measure to require new washing machines to be sold with a microfiber filter to prevent filaments from flushing into the sewer and then into waterways.

Related: Hunt For answers shows Oregon rivers not immune to microplastic pollution

In Olympia, several Washington legislators are copying ideas previously passed by Oregon including holding manufacturers responsible for reducing their plastic packaging and increasing recycling over time. A freshman Democrat from Tacoma, state Rep. Sharlett Mena, proposed to ban those little plastic toiletry bottles and wrappers in hotels in favor of refillable bulk dispensers. And there's a new try to pass a bottle bill for Washington, which would entail a 10-cent deposit and redemption system for most plastic, metal and glass beverage containers.

Prospects for passage are by no means a slam dunk. State and national industry lobbyists are lined up to ask for more transition time or pointing out unintended effects. For instance, Peter Godlewski of the Washington Association of Business testified this past week that banning plastic foam used to float boat docks, as proposed, could actually result in more trips to landfills.

"Air-filled docks are much less robust than the foam-filled version and both fail more frequently and have a shorter lifespan. So, they need to be replaced more frequently," Godlewski told the state House Environment and Energy Committee.

Last summer, California passed the nation's strictest law to reduce plastic pollution. The state mandated that two-thirds of all plastic packaging must be recyclable or compostable within the next decade.

In California, industry and environmental groups came to the table to hash out compromise timelines to reduce single-use plastics under the threat of a ballot measure that was subsequently withdrawn. Intense behind-the-scenes negotiations in that vein are now happening in Washington state on the 2023 plastic recycling/producer responsibility/bottle deposit legislation. A previous version died a quick death during the 2022 legislative session in Olympia in the face of broad opposition from the grocery industry, waste haulers and plastics trade groups.

“We share the goal of an effective producer responsibility system that can help achieve a circular economy and reduce plastic waste,” said Washington Beverage Association executive director Brad Boswell in an emailed statement. “We have been working closely and diligently with lawmakers and environmental groups for three years on developing a well-designed system that improves recycling rates in Washington and we look forward to continuing that work.”