Sam, a student in OPB's Class Of 2025 project, looks down from the balcony outside his family's apartment in Springfield, Ore., June 21, 2022.

Rob Manning / OPB

Sam is starting his sophomore year at Springfield High School. He lives in a quiet old neighborhood in an upstairs apartment with his dad and brother.

Jacob is also starting 10th grade and lives with his dad. He lives in a new subdivision in the small Clackamas County city of Molalla.

A decade ago, Sam and Jacob entered kindergarten together at Earl Boyles Elementary School in Southeast Portland, where they joined OPB’s Class Of 2025 project.

Like thousands of high school students across Oregon, Sam and Jacob have faced difficulties the last few years brought on by school disruptions, health challenges, the shortcomings of distance learning and the discomfort of transitioning back to in-person instruction.

In 2021, more than a quarter of Oregon ninth graders failed to earn the number of credits required to stay on track to graduate on time. Numbers aren’t available yet for 2022, but the failure rate from 2021 shows a troubling 10% increase in the number of freshmen who fell short of the credits needed to stay on track compared with previous years.

Those numbers are not good news, considering the goal Oregon set a decade ago, and clarified in 2018, that all students starting with the Class Of 2025 would complete high school.

Jacob’s quarantines

Jacob was out sick for two weeks early in the last school year. He didn’t test positive for COVID, but he had a fever, and other symptoms. Then, when he went back to school, he was sent right back home.

“I got quarantined,” Jacob remembered. So he was out for several days, following the school’s protocol for students who were potentially exposed to COVID-19 at school.

“Then when I came back [...] I got quarantined again,” Jacob said. “So it’s back to back [...] and then when I tried to get back into it, I just gave up for the first trimester.”

Josh Tompkins, left, sits on a couch at the family home in Molalla, Ore., beside his son, Jacob, a student in OPB's Class Of 2025 project.

Rob Manning / OPB

Jacob says he missed learning some important concepts, particularly in math, though he was able to work his way back in science — a class at which he’s always been good.

The consecutive quarantines were so upsetting to Jacob’s dad, Josh Tompkins, that he called Molalla High School to complain about all the class time Jacob was missing.

“So I told the school, ‘If this happens again, he’s not coming back.’ Because why?” Josh Tompkins said. “He’s missed so much school. It was ridiculous.”

Sam’s disinterest

Down in Springfield, Jacob’s former classmate Sam also missed two weeks of school due to a prolonged illness. But Sam was already struggling with the adjustment to high school and missing class made the difficult transition to a big, unfamiliar school more uncomfortable. He didn’t have many close friends. He was falling behind academically, and he wasn’t feeling motivated to put in the work to catch up.

“I just stopped having more — what’s it called? — the desire to go to school. And I started skipping more instead of going more,” Sam said. “My mindset was like ‘If I don’t even do the work, what’s the point of going?’”

Sam says at times his father would confront him about skipping school. His attendance would improve, briefly.

“He would yell at me about it, and I would like go the day after and then like a day after that and like go the day after that… and then just not go,” Sam said.

Sam said he’d try to focus on his work, but would get distracted. He and his dad say he had some conflicts with classmates that made school a lonely place — especially early in the year.

Sam and Jacob decide on summer school

By the end of the school year, Sam and Jacob were in deep holes. Jacob didn’t pass math, English and history. Sam also needed to repeat those three classes, as well as physics.

The state of Oregon won’t publish data on how many freshmen fell behind the expected number of credits last year, but the most recent state data from 2021 shows the difficulty — with only 73.6% of ninth graders having earned enough credits to be considered on time for graduation.

Oregon has measured “Ninth grade on track” for the last several years, because students who fall behind that first year of high school are far less likely to graduate than freshmen who passed all their classes.

Rodger Kennedy (right) stands next to his son, Sam, a student in OPB's Class Of 2025 project, outside their apartment in Springfield, Ore.

Rob Manning/OPB / OPB

“[A] preliminary ODE study showed that on-track students were more than twice as likely to graduate within 4 years as their off-track peers, after adjusting for demographic factors,” according to the Oregon Child Integrated Dataset, a state-funded research project launched in 2019.

At Sam’s high school — Springfield — the percentage of freshmen on-track fell from 92% before the pandemic down to 78% in 2021. At Molalla High, where Jacob goes to school, the on-track percentage was also in the 90s before the pandemic — and plummeted to 58% in 2021.

When Jacob learned he’d have to make up three core classes, he and his dad had a frank conversation. Jacob had a choice.

“So my dad gave me an opportunity, said yes or no if you want to go to summer school and I said yes,” Jacob recalls. “Stuff happens. I’m not really frustrated about it. Just I want to graduate, and I want this to be behind me.”

Sam and his dad, Rodger Kennedy, talked it over, too. And they also reached an agreement, which also involved summer school.

“He will have to make those credits up,” Rodger Kennedy said. “So we’ve worked out a game plan for some summer school, a little night school, to get himself caught back up, so he can still graduate on time.”

Just as the pandemic caused many high schoolers to fall behind on credits, big increases in state and federal funding led many school districts to expand summer offerings the last two years.

The result was a big jump in the number of students taking classes the last two summers. At Jacob’s high school, Molalla High, summer school enrollment for high schoolers quadrupled from 27 in 2019 to 109 this past summer. Sam’s school district, Springfield, noted that summer offerings were new at the high school, and that interest was high, but officials didn’t provide numbers.

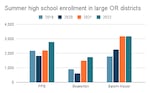

Summer enrollment among high school students has gone up substantially over the last few years at Oregon's three largest school districts.

Rob Manning / OPB

Oregon’s three largest districts all saw big increases. Enrollment in summer high school classes for Portland Public Schools has gone up 22% since before the pandemic, according to numbers the district provided. The number of summer high schoolers in Beaverton and Salem-Keizer went up even more, nearly doubling since 2019.

School administrators are quick to point out that not every student going to summer school is attending to make up a class they didn’t pass. Some want to get ahead, or take courses that might be hard to schedule during the regular school year.

What Jacob and Sam are looking forward to

With 10th grade about to start for Jacob and Sam, both see something they’re interested in on the horizon. It’s the same thing, actually: welding.

Sam found welding partway through the year, and the class gave him a reason not to skip school.

“Because I went to welding I like made new friends,” Sam said. “I found this teacher I really liked so I just like kept going, and it was OK, I guess.”

Sam is excited to take another welding class and other hands-on courses, such as ceramics and wood shop. His father, Rodger, sees a broader benefit from Sam finding a class he liked.

“That kind of piqued his interest and gave him a reason to want to go and you know follow through all the other aspects of school, not just the electives but you know to be able to graduate,” Rodger Kennedy said.

Jacob’s interest in welding is more strategic. He sees it as part of a life plan he’s had for himself for a while — to one day run his own auto repair shop. He sees welding as a “good thing to start” as he prepares for a future as a mechanic and possible business owner.

His dad, Jacob Tompkins, sees other areas where Jacob may need to apply himself, if he’s going to be able to work on the technologically advanced “supercars” as the older Tompkins calls them. Jacob is skeptical.

“I’ll have even more work,” Jacob tells his dad.

“That’s what school is for,” his dad responds.

“Older cars are way better and easier to work on, and they look way better too,” Jacob argues.

“OK,” Josh Tompkins responds with a laugh. “Then we’ll have to re-evaluate this.”

But Jacob and Sam still have a climb ahead of them.

Jacob made up some of his credits in summer school, but not all of them. Sam didn’t end up taking the summer classes he signed up for. The families are adjusting their plans, with the same goal in mind: that both boys will graduate on time in 2025.

The dads say their sophomore sons understand what’s ahead of them and are willing to put in the work to get through high school successfully.

Editor’s Note: This story has been updated with information received from the families after the story initially published.