OPB senior political reporter Jeff Mapes spent more than a year researching, reporting and producing “Growing Oregon,” a six-part podcast and web series looking at the evolution of Oregon’s unique approach to growth and the impact it has on our lives today. Here’s the story behind the story. Listen to Episode 1:

I’m standing on what feels like a sea of dirt in Oregon’s Willamette Valley.

A half-century ago, this newly plowed field was pretty much the epicenter of the battle over the future of Oregon’s vast landscapes.

Oregon’s population was booming and developers had their eyes on this verdant valley — which also happened to be the home of two-thirds of the state’s population.

I’m here to talk to Mike Bondi. He ran Oregon State University’s 160-acre North Willamette Research and Extension Center, although he retired just before publication of this story. I want to understand what makes the valley so special — and why so many Oregonians fought to save it.

“I always say we can grow everything in the Willamette Valley,” says Bondi, “from asparagus to zucchini.”

Commercial farmers grow more than 200 different crops in the valley. That’s a wider variety than in any state except for California, he adds.

Mike Bondi walks through Oregon State University’s 160-acre North Willamette Research and Extension Center in Aurora, Ore., on July 1, 2022. Bondi, the former director at the center, says the soil in the Willamette Valley is what allows such a variety of crops to be grown.

Kristyna Wentz-Graff / OPB

“It all starts with soil,” Bondi explains as we crumble softball-sized clods of dirt. He describes how prehistoric floods broke the Cascade Mountains tens of thousands of years ago and deposited deep layers of dirt that in essence created the valley.

Bondi and other researchers work closely with farmers to help them figure out the future of agriculture in Oregon.

When hard cider became a thing, they planted apple trees to figure out which ones produced the best fruit. They’re helping kick-start a boutique olive-oil industry in Oregon. And in one field, they put up solar panels to see how best to grow crops under and around them.

Fifty years ago, this agricultural bounty was at risk. The fight to preserve the valley was the biggest factor that led to Oregon’s unique land-use system — one that eventually produced what are arguably the toughest statewide growth management controls in the country.

These restrictions may be the biggest thing we ever did in modern-day Oregon. They put urban growth boundaries around every city. They restrict the building of rural homes, foremost on prime farmlands. They make this place what it is.

But for all their importance, many Oregonians don’t know much about the laws governing our land. I think of them as the hidden operating system of our built environment, most humming away in the background.

Test crops growing at Oregon State University’s 160-acre North Willamette Research and Extension Center in Aurora, Ore., July 1, 2022.

Kristyna Wentz-Graff / OPB

Only a few states ever attempted anything on our scale. And now I’m on a journey to figure out how all this happened. And along the way, I’ll explain why it affects so many things you might not have thought about.

Because we limit where you can build homes, it’s led planners to push for more compact communities. Done right, that can help reduce driving and climate pollution. It affects the size and types of homes we build. It increases the opportunity to bring more racial diversity to neighborhoods. But it may also accelerate a shift away from the single-family homes that have long been seen as the mainstay of the middle class.

When urban sprawl first became an issue

Before we get too deep into this story, I should explain that I’m a child of the ‘60s. I grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area watching the spread of suburbia.

To me, that meant seeing rolling hills of oak and eucalyptus disappear to make room for yet another subdivision.

My father grumbled about it. He grew up south of Oakland in Hayward, which was then a small farming community.

Like many kids then, he’d help out at harvest times in the fruit orchards. From the top of a farm ladder, he could see San Francisco’s elegant 1930s skyline.

But by the ‘60s, the orchards and farms were no longer in Hayward, or pretty much anywhere in the Bay Area. My dad told me stories like this all the time, about the California that no longer was.

My mother thought everything was great. She was in sunny California. She felt lucky to escape a dour childhood in Fort Wayne, Indiana. The people in her new home were interesting, dynamic, living their best lives.

I felt somewhere in between — privileged to grow up in a place so many people wanted to be but also with this innate sense of something lost.

Of course, that feeling isn’t unique.

We’ve always fought over who controls the land in this country, no more so than in the West.

In the 1850s, white settlers were promised free land in Oregon, displacing the Indigenous people who lived here. There were repeated battles for control of the wealth from the great forests and powerful rivers.

The end of World War II was another pivotal moment. That was when the country was really reinventing itself. We started in earnest to build the modern America you see — the landscape dominated by cars, strip malls, freeways and single-family homes.

Adam Rome

Douglas Levere / University at Buffalo

“After the war, there is this population boom,” explained Adam Rome, an environmental historian at the University at Buffalo. “Housing was incredibly scarce, and the ability to mass-produce housing — everyone involved was treated like a hero to be able to make cheap, decent houses.”

Rome authored a book, “The Bulldozer in the Countryside,” that chronicled the rise of a new industry that built houses at a scale no one had ever seen before. Post-war prosperity and the growing ubiquity of the automobile led developers and customers further into the countryside.

Builder William Levitt epitomized this new approach, creating a brand-new city — Levittown — that housed 60,000 people.

Like so many of these communities, including in Oregon, it was white-only. These segregated developments were spurred on by federal agencies that refused to guarantee home loans to Black people trying to buy in mostly white areas.

Developers also used racial covenants and other tactics to restrict sales to anyone who wasn’t white. And speculators fueled block-busting — the tactic of spreading fear among white homeowners in cities that they needed to sell now to avoid catastrophic drops in their home values. We entered an era when segregation would become even more pronounced in much of America.

There was something else people didn’t talk about at first: the environmental cost of progress.

Thanks to new, more powerful earthmoving equipment and building techniques, developers were remaking the landscape. Marshes were filled in, hillsides leveled, trees razed, and streams diverted into culverts.

“They bulldoze the land, whatever was on it,” Rome said. “They leveled high spots and filled in low spots. …That’s this uniform building space. And again, over the course of a generation, people started to realize that that way of thinking caused a lot of problems.”

Runoff from new subdivisions polluted streams and lakes — even bays and oceans.

And then there was, to speak plainly, the problem of poop.

Developers wanted cheap land. So they often jumped beyond city water and sewer systems. As a result, new homeowners relied on wells and septic tanks. A lot of those failed.

“The septic tanks would pollute the wells,” Rome said. “They’d turn on the faucet and crud would come out and not just sewage, but you know, detergent foam from the laundry.”

He said people joked about it, toasting detergent cocktails and brown beer. Humorist Erma Bombeck, who chronicled the suburban lifestyles of my youth, titled one of her books, “The Grass is Always Greener Over the Septic Tank.”

“But it was a horrifying thing,” Rome said of the pollution. “People had their basements flood, or their yard would fill up with sewage.”

Postwar housing development in Levittown, Pennsylvania, circa 1959, one of the first mass-produced suburbs in the country.

Courtesy of the National Archives

Many new suburbanites started to complain about moving to a country-like setting, only to find that they were soon surrounded by even newer subdivisions.

A 1969 documentary, “Multiply and Subdue the Earth,” quoted one new suburbanite saying that she and her family were “looking for some peace and quiet and a lot of people we can relate to in our community.”

And now, she added, “we find that this is all disappearing, with another raping, the raping of our hills.”

Urban sprawl first became a big issue in the late 1950s. By 1964, Interior Secretary Stewart Udall issued a report stating that an area the size of Rhode Island was being converted from country to city and suburb every year. Development “has made a bitter sandwich of much of our land, buttering our soil with concrete and asphalt,” the report concluded.

The loss of so much countryside, the foul air and the stinking water, all helped create the modern environmental movement.

And then there was just the sheer number of people. They called my generation the baby boomers for a reason. There were just so many of us.

We were told the world faced mass starvation if we didn’t stop reproducing so much. The movement to stop population growth became a potent political force.

California was on the leading edge of all of this. Its population grew larger than any other state. Massive housing developments sprouted helter-skelter into the countryside. Its air pollution was the worst in the nation. And its traffic jams were legendary.

And Oregonians felt all of this was heading right toward them.

Quality of life in Oregon

On Nov. 21, 1962, viewers tuned to Portland’s KGW-TV for a documentary, “Pollution in Paradise,” that changed Oregon.

“No part of America still retains more of nature’s original work than the state of Oregon, a paradise for those who treasure the unspoiled, in sight, in smell, in sound,” anchorman Richard Ross said at the beginning of the one-hour documentary.

“But who are these foul strangers in Oregon’s paradise?” he added, as indignant music swelled over footage of a heavily polluted river.

Undated image of Tom McCall with his catch of the day.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library

Political reporter and commentator Tom McCall picked up the narrative. In his distinctive accent — the voice of his upper-crust New England upbringing — he called out industrial polluters by name. And he spotlighted local sewage officials who were unable to keep up with growth.

Multnomah County was forced to curtail building permits in the 1950s because of leaky septic tanks. In the Metzger sanitary district in Washington County, one in every five homes “was discharging raw sewage in a manner that threatened an outbreak of polio, typhoid and hepatitis,” McCall said.

It wasn’t just foul water.

“For 50 to 60 days every year,” McCall told viewers, “inversions hold all Portland’s pollutants close to the ground, and give Portlanders more than an inkling of what smog-invested Los Angeles has to endure.”

Watching the documentary recently made me realize how scary it must have felt back then — how surprised people were that their prosperity and modern conveniences threatened things as basic as clean air and water.

“Pollution in Paradise” was a sensation. It forced tougher regulation in Oregon — and revived McCall’s political career.

He’d been the top aide to Republican Gov. Douglas McKay, where he learned how to exercise power, Brent Walth explained in his biography of McCall, “Fire at Eden’s Gate.” In 1954, McCall defeated Portland Congressman Homer Angell in a Republican primary. But McCall was defeated in the general election by Democrat Edith Green.

McCall went back into the news business, his political career seemingly over.

In the wake of the documentary, he made a spectacular return. He was elected secretary of state in 1964 and won the governorship just two years later. McCall was now a leader of the new breed of moderate-to-liberal Republicans who increasingly dominated Oregon politics.

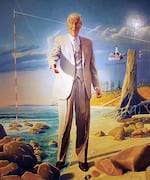

Tom McCall, governor of Oregon from 1967–1975.

Courtesy of the Oregon State Archives

McCall quickly made his top priority clear.

“The umbrella issue of the campaign and of the decade in Oregon is quality, quality of life in Oregon,” he proclaimed in his inaugural address.

McCall often said that the richness of life in Oregon was closely tied to the land. He talked about the state’s stunning beauty and unmatched recreational opportunities.

This resonated with Oregonians. The state had a strong middle class dominated by a still-growing timber industry, explained Norma Paulus, another prominent liberal Republican. She served in the state Legislature and as secretary of state before losing a race for governor.

“It was a very stable society,” Paulus said in a 1999 interview with the Oregon Historical Society. “The average person thought that the beach belonged to him. The average person thought that Mount Hood belonged to him. And, you know, it was part of their heritage, so there was great understanding of the need to protect it.”

This stable society also led both parties to the political middle. At the time, environmental issues were widely seen as a unifying issue, both in Oregon and nationally — unlike, say, the Vietnam War or civil rights.

“Everyone understood — Republican, Democrat, blue state, red state … that our environment in a lot of ways had gotten dramatically worse during this post-war boom,” said Rome, the environmental historian.

Protecting Oregon’s cherished landscapes

Just a few months after taking office, McCall demonstrated how he would protect Oregon’s cherished landscapes. It involves the ocean beaches, and his actions on behalf of coastal protection may be the most celebrated part of his legacy.

A portrait of Tom McCall in the Oregon State Capitol, painted by Henk Pander.

Courtesy of Oregon State Archives

When I think of this chapter in his career, I think of McCall’s official portrait in the state Capitol. Unlike the stodgier portraits of the state’s other governors, the McCall painting almost has the feel of a comic book. At 6-foot-5, he was a tall guy, and this picture plays on that; it shows him bestride the rugged coast like some kind of Marvel superhero.

The story behind the portrait is plenty dramatic. In the 1960s, coastal businesses and developers started claiming part of the beach for their own use.

They said the public only owned the sands below high tide. Oregonians were outraged. They thought the entire beach had been public since Gov. Oswald West got the Legislature to declare them a public highway in 1913. At the time, the beaches often provided transportation along parts of the coast. But West also saw the value of securing them for a broad variety of public uses and enjoyment.

In 1967, the Legislature stalled action on McCall-supported bills to make it clear that the entire beach belonged to the public. McCall stormed out to the coast one weekend by helicopter. He invited the press and university researchers to join him while he visited several beaches.

In Cannon Beach, the researchers drove stakes up and down the beach to show what parts would be protected under different standards. McCall narrated the action for reporters and glowered at a motel where the owner had blockaded part of the beach for his own customers.

Governor Tom McCall standing outside log barricade on beach in front of Surfsand Motel at Cannon Beach, Ore., May 1967.

Leonard Bacon / Oregon Historical Society Research Library

McCall concluded that the state should claim all of the sand up to 16 feet above sea level. Not so coincidentally, that’s where the line of vegetation tended to start. The logjam broke as key legislators worked out a deal that protected the beaches, as well as access to them. And McCall won his first big victory in office.

Next, he took on land use.

‘Come visit us again and again. But for heaven’s sake, don’t come here to live’

Everyone could see what was happening in the Willamette Valley. The valley was both the heart of the state’s agricultural industry and home to two-thirds of Oregon’s population.

The Willamette Valley watershed is home to three of Oregon's largest cities. Data Source: USGS

MacGregor Campbell / OPB

Booming auto ownership made it easier for people to live farther from their jobs. And many people wanted to live a few miles out of town without necessarily being farmers.

Oregon farmers were normally a conservative bunch. But they began demanding protection from unchecked growth.

Hector Macpherson, a dairyman near Corvallis, recalled all the homes going up near him in a 1992 interview with the Oregon Historical Society:

“[I] thought they were coming toward me, and that I would be surrounded,” he said. “We needed rural zoning to keep them out.”

The problem, he said, was that “some counties were doing a pretty good job of it — and other counties were doing absolutely nothing.”

Macpherson said Oregonians just had to look south to see what could happen.

California was already losing many of its agricultural areas, from the Santa Clara Valley in the Bay Area to the orange groves of greater Los Angeles.

Macpherson was one of those farmer-intellectuals, a well-read guy always thinking about where agriculture was headed. He didn’t have McCall’s flamboyance. But he had the temperament for painstaking detail. And eventually, he would become McCall’s most important partner in the fight for growth management.

McCall first tested the Legislature’s appetite for controls in 1969. He sent state legislators a dire message warning that sprawl is “introducing little cancerous cells of unmentionable ugliness into our rural landscape, whose cumulative effect threaten to turn this state of scenic excitement into a land of aesthetic boredom.”

At first, it seemed he had a good head of steam, thanks to strong support from the agricultural community.

Rep. Joe Rogers, a Republican farmer from Independence, told his colleagues that “helter-skelter developments” led him to support new land controls to protect valley agriculture.

“If you’d had said 10 years ago that a committee predominantly made up of farmers would come in sponsoring a zoning bill, I would have said you were crazy,” he said at one hearing. “But times have changed.”

However, only one of the four land planning bills supported by McCall that year passed.

Many feared that McCall and company wanted to take away their private property rights. Conspiracy theorists pushed a lurid trope that a communist-inspired conspiracy was being run out of a Chicago office building — and it was trying to destroy local control. In reality, the building housed several rather humdrum associations, such as the National Legislative Conference and the Council of State Governments.

McCall’s one win in 1969 — Senate Bill 10 — required counties to zone all of their land. They were supposed to meet several goals, such as preserving open space and farmland. If they didn’t do the job, the governor could do it for them.

But the bill turned out to be toothless. McCall didn’t have the money or the tools to enforce the law.

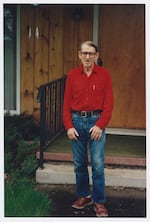

Hector Macpherson, Jr., 1992, at his home in Oakville, Oregon.

Clark Hansen / Oregon Historical Society

Macpherson said McCall threatened a takeover “knowing it was really a paper tiger. He really couldn’t step in and do anything.”

Still, the passage of the law did show that people wanted action. In fact, voters rejected a ballot measure that would have overturned the law in 1970. At that point, it was still unclear if the new policy would have a major impact.

That year, voters also gave McCall a second term.

Macpherson won election to the state Senate the same year. He began working behind the scenes with McCall’s aides to draft tougher legislation.

McCall entered his new term making a big public splash about his commitment to Oregon’s livability. McCall told CBS News that he didn’t intend to allow Oregon to become overrun with sprawling unplanned growth as California had. McCall said his message to newcomers was:

“Come visit us again and again. This is a state of excitement. But for heaven’s sake, don’t come here to live.”

Nothing McCall ever said or did attracted more attention than that statement. And yet the sentiment didn’t dissuade people from moving here. Oregon’s population grew faster in the 1970s than it did in the 1960s.

Today, McCall’s comment makes me flinch. It strikes me as nativist. After all, Oregon was around 97% white at the time.

In fairness, McCall had been a strong supporter of civil rights since the beginning of his career. But that was an era in which many Oregonians didn’t think much about diversity. And many found in his remarks a badge of state pride and uniqueness.

More than a few businesspeople criticized his visit-but-don’t-stay remarks out of fear the sentiment would hurt economic growth.

For his part, McCall repeatedly insisted he didn’t want to stop growth. He just wanted to make the point that Oregon didn’t have to sell its soul — its livability — to prosper.

“Forget about adding smokestacks. Forget about adding jobs,” McCall later said. “And maybe we won’t have as much bread on our tables, so to speak, right now. But if you want industry, you’re going to have so much clean industry that it’s going to be lined up in a long queue, waiting to get into Oregon, because we’ll have the things that enlightened industry wants … when everybody else has destroyed them.”

‘The system hasn’t failed, there is no system’

Back at that research farm near Wilsonville, Mike Bondi points to a line of rooftops across the road.

He’s looking at Charbonneau, a planned development built in the early 1970s.

Lynn Gearhart, left, tends to her garden at her home in Charbonneau, a planned development built in the 1970s in Wilsonville, Ore., June 14, 2022. The community was built on active farmland, and farming continues today on the east side of the development, right.

Kristyna Wentz-Graff / OPB

“Great neighbors. We all cooperate together,” Bondi says. “Everybody wants to live next to the farm, but they don’t necessarily appreciate it when we’re spreading manure.”

Charbonneau is a pleasant place. Winding roads and a wide variety of homes surround a golf course. Most residents are seniors. Life here feels laid back.

But Charbonneau was once a dagger pointed at the heart of agriculture in the Willamette Valley.

Developers first announced their plan to build a community for 2,000 people in 1971. The banner headline in The Oregonian appeared just as bulldozers were clearing the farmland for construction.

Portland’s business elite put up the money, some $100 million. It quickly attracted opposition, being so large and so far from the existing spread of suburbia. (Wilsonville then was just a small town of 1,000.)

McCall formed a task force to look into the development. The resulting report warned that Charbonneau threatened to raise farmland prices and set off a gold rush by urban developers.

Farm fields back a manicured lawn at Charbonneau, a planned development built in the 1970s in Wilsonville, Ore., June 14, 2022. It was built on 477 acres of active farmland and farming continues east of the homes.

Kristyna Wentz-Graff / OPB

“Clearly, if Charbonneau is a success,” the report said, “adjacent farmlands will be sold to other developers hoping to capitalize on the high-quality image this development projects.”

The report also noted that plenty of other smaller developments were also in the works — and that more than a quarter of the valley’s agricultural land had already been paved over.

On top of that, the report said there was nothing the state could do to stop Charbonneau or other similar developments.

The builders weren’t breaking any rules meant to stop unchecked sprawl. There simply were no rules.

“The system hasn’t failed,” the report concluded. “There is no system.”

Coming on July 22: Part 2, the battle to create a system.

The Growing Oregon audio story is available through the OPB Politics Now podcast feed.

OPB Politics Now

OPB Sta