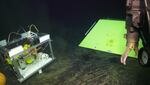

A spider crab decides that seismometer deployed by scientists on board the research vessel Thompson is the place to be on the ocean floor.

ROV Jason, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

Reporter’s notebook: OPB science reporter Jes Burns shares a strange tale of “crabotage” that emerged as scientists aboard the research vessel Thompson tried to answer complicated questions about the Axial Seamount.

Being out on the research vessel Thompson in the middle of the ocean means never really hearing the ocean at all. There’s engine noise and exhaust blowers and climate control and winches and wind — but very few actual waves.

Being out on a research ship 250 miles away from land means the science never stops. It’s a 24-7 buzz of prepping, deploying and recovering geologic sensors trying to understand complicated questions about what makes volcanos tick — specifically the undersea Axial Seamount, which is about 250 miles west of Cannon Beach.

Being out on the research vessel Thompson also means witnessing firsthand a drama beneath the waves. It’s a story of human against nature, a battle of attrition, on the top of the Pacific Northwest’s most active volcano.

It’s a story I’ve come to call “The Spider Crab and the Seismometer.”

“We expect sabotage, crab sabotage. Because there’s obviously a battle going on between Jason and the crabs at Axial Seamount,” said Oregon State University volcanologist Bill Chadwick, the head scientist on the ship.

The saga starts on a Tuesday, our second day out at sea, and the ROV — which stands for “remotely operated vehicle” — called Jason is cruising along the ocean floor. It’s got these titanium arms with pincher hands that can pick up things off the bottom, move sensors around, maybe even play the violin if given the opportunity. It’s pretty impressive.

“It looks kind of easy, but it’s actually really hard. Moving the vehicle just right. Using the arm to do really delicate tasks,” Chadwick said.

ROV Jason and its arms are controlled by a pilot in a tricked-out shipping container that acts as a control room up on deck — everyone just calls this space “the van.” The van is dark and cold and serene. There are video feeds from Jason’s cameras covering one wall. They show the parts of the ocean floor as Jason glides over them — lava flows, pillars, cliffs, hydrothermal vents — some which no human has ever seen before.

We spent a lot of time in the van.

The research team had just dropped overboard a specialized seismometer designed to reveal things like the shape of the magma chamber under the volcano. That seismometer is so sensitive to vibration, engineer Ted Koczynski said it needs a Smart Car-sized plastic dome over the top to protect it.

“The whole idea of that shield is to stop any currents from getting in and tweaking that seismometer,” said Koczynski, who, when not at sea, is based at Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory in New York.

It was Jason’s job to pick up the dome from the seafloor with those titanium claws and drop it down over the seismometer. A group of us were in the van behind the pilot watching Jason work.

The ROV was just about to place the dome over the instrument. Then we saw it.

Expedition leader Akel Kevis-Stirling prepares to deploy the remotely operated vehicle Jason to explore the Axial Seamount, a sub-sea volcano about 250 miles off Oregon's coast.

Jes Burns / OPB

While Jason had its back turned, a big orange spider crab — probably about two feet across — crawled into the instrument and took up residence on top of the seismometer.

“I didn’t put the crab into my dive plan,” deadpanned Bill Chadwick, because he knew this was going to be a problem.

A seismometer sensitive enough to respond to a slight current is definitely sensitive enough to feel the tippy taps of little crabby feet.

After some discussion of strategy, Operation: Crab Extraction began.

Because the crab was so far into the sensor housing, there was worry that Jason’s claw could damage the instruments. So, they decided to try the “Slurp,” Jason’s powerful vacuum hose.

This prompted Jason’s pilot, Tito Collasius, to utter the best sentence on the cruise so far: “Stand by to slurp.”

Collasius manipulated the claw to grab the Slurp’s vacuum nozzle.

“That’s for you buddy,” he says, as he moves it towards the crab.

“We’re coming after you. This is your last warning,” Chadwick added from Collasius’ elbow.

In the moment, it appeared as if the mere threat of slurpification would be enough. The crab saw, or somehow sensed, its impending doom and started to move away.

But then, showing John Wayne levels of grit, the spider crab stopped short of leaving all the way.

“His name is Moriarty,” Collasius said, referring to the criminal nemesis of Sherlock Holmes.

At this point, it was claw time. And in a battle between Jason claw and crab claw, Jason had the advantage.

A cheer erupted in the van as the claw made contact and slowly pulled the crab out.

”They ended up grabbing it by the legs and flying away with it. It was so funny,” recalled Kelly Chadwick, the data logger on duty at the time.

The pilot deposited the crab about 65 feet back, and the crab scurries away.

ROV Jason smoothly pulls a spider crab from its hiding place on top of the seismometer.

ROV Jason, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

The tale of the spider crab and the seismometer made its way around the ship for a few days to the enjoyment of all. When you’re stuck on a boat in the middle of the ocean, this is A+ entertainment.

And that could have been it for the story. But as time wore on, suspicious things started happening below the waves.

First, one of Jason’s propulsion thrusters went out, causing it to have to move sideways across the ocean floor, which got Chadwick speculating.

“We had to remove the crab forcefully from one of the instruments. And then one of Jason’s thrusters goes out, so we have to move around like a crab. That was a point for crab. And so it’s kind of even,” he said.

But the score wasn’t even for long. As the scientists were pulling in the seismometer and shield to check the data collected, the shield part mysteriously vanished. We saw it leave the seafloor when Jason strapped a float to it, but when Pete Liljegren, another Lamont-Doherty engineer, recovered the float on the surface, the shield was gone.

“I think that was the same instrument where Tito got in the altercation with the crab before he put the shield on. The motive is there,” he said.

Of course, on a boat full of scientists and engineers, not everyone was susceptible to such outlandish crab-based speculation.

I posed the prevailing crustacean-centered theory to Kocynski: “There’s a theory going around that the loss of your hood is crab-related, that it may have been an orchestrated effort by the crabs.”

“Nah,” he said.

He paused, shaking his head dismissively.

“It had to be the seal. Crabs are good – but they don’t have any strength. The seal, now, is a clever animal,” he replied.

But for Chadwick, all the proof he needed was at his instrument sites scattered underwater on the volcano.

“At the last benchmark, there was a crab waiting for us there…taunting us,” he said.

And listen all y’all: For this reporter’s money — it’s crabotage.