At their worst, methamphetamine-fueled emergency department visits involve patients who are psychotic, erratic and violent. It can take several people to secure and sedate them.

That’s what happened to one man, now nearly 10 years sober, on one of the worst nights of his life. High on meth and drunk, he attempted suicide under the delusion that he “was the cause of evil to the world,” he said. His family called 911, and first responders secured him to a gurney, gave him a shot of thorazine, and took him to a hospital emergency department. He woke up in the hospital’s psych unit less than 24 hours later. Within three days, he was out and soon using again.

Today, the middle-aged father draws on his experience with meth addiction — and on what he witnesses as a street outreach worker in Portland — to help plan Oregon’s first meth stabilization center. The man spoke about his past with The Lund Report on condition of anonymity to protect his privacy due to the stigma associated with meth use.

Whereas a sobering center typically offers up to a 24-hour stay, stabilization allows more time, which is what people coming down off meth need, according to Robin Henderson, the chief executive of behavioral health at Providence Oregon.

Providence’s Portland-area hospital emergency departments saw 1,852 methamphetamine-related visits last year. Across Multnomah County there were nearly 7,500 meth-related emergency department visits last year. Henderson said these patients could benefit from more time than they receive in emergency rooms.

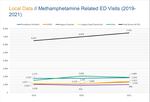

This Multnomah County chart shows a rise emergency department visits in different hospital systems in the region from 2019 to 2021.

Multnomah County

The psychosis that methamphetamine can spark in its users can show up as paranoia and vivid hallucinations. They often believe someone is out to get them, leading to aggression toward people trying to help them, like doctors and nurses. And, busy hospital emergency departments are not set up to provide the time and specialized care that could lead meth users to recovery and treatment.

“It’s hard to use your traditional methods of calming someone down who is really responding to stimuli that there’s no way you would even know existed,” Henderson said. She said emergency room staff were handed “a methamphetamine addiction problem with no playbook.”

A stabilization center would be a place where first responders could take people in the throes of a meth-induced mental health crisis, say the center’s planners. It would be better equipped to treat patients and connect them to resources, using professionals trained in helping people who have a history of trauma.

The location, opening date and funding are still being determined. But nearly $2 million has been spent on planning for a new stabilization center and the effort to open such a facility in the city center is gaining momentum.

Meanwhile, meth has become increasingly deadly. Nearly 1,000 Oregonians died from meth use from 2019 to 2021, according to the most recent data available from Oregon State Police.

The emergency room visits and death toll are symptoms of Oregon’s long-enduring methamphetamine use problem. Since the ‘90s, Oregon has ranked among the states most impacted by the drug, and in 2020, Oregonians had the highest rate of meth use in the country, according to the most recent National Survey on Drug Use and Health data. Nearly 2% of those surveyed over age 12 reported meth use within the past 12 months. And in recent years, meth has become cheaper, more widely available and more toxic.

Henderson has called health systems around the country, asking them what they’re doing about the meth situation, she said, and no one has a good answer.

Meth-related emergency room visits have been rising steadily in Multnomah County in recent years. Last year, they exceeded visits related to alcohol, which typically top the list. And when people suffering from meth psychosis don’t land in the hospital, they’re often taken to jail.

That’s why meth emerged as the focus of the substance use crisis triage center concept that Henderson and other area health care providers have been discussing with Multnomah County and Portland officials.

“I think a meth stabilization center needs to look like a place that you can stay for five to seven days while you get clear,” Henderson told The Lund Report. She said the time it takes for someone coming down off meth to potentially be receptive to treatment is much longer than for someone experiencing a medical crisis related to heroin or alcohol.

“We need a space to buy time,” she said. “Because right now, all we’ve got is, ‘we can get you sober enough to where OK, you’re here, but then we’ve got nothing else for you because nobody’s really quite ready for you yet.’”

Medical support for withdrawal management as well as peer support — mentorship and other services from people who have lived experience with addiction — are also crucial, Henderson said.

“We need a safe place for people to be able to find and inspire hope and understand, really, that this space isn’t to send you back to the street. This space is to connect you — whether it’s intensive outpatient or outpatient or inpatient or residential, or whatever it is,” she said.

The man who landed in the hospital high on meth more than a decade ago said it would have been less traumatic if he’d been treated differently. “A safe place to be able to go through the process of detox, and knowing that I’m safe, and knowing that there’s follow-up, and knowing that there’s support wrapped around it would have been helpful,” he said.

A plan to fill a void

Portland’s only sobering center, run by Central City Concern, closed in late 2019. The nonprofit cited an inability to handle the increase in people intoxicated on drugs like meth.

Central City Concern's sobering center, which closed in 2019. Back in the 1980s, the center helped 20,000 people a year. The year before it closed, the sobering center helped just 3,700 people. Experts say what Portland needs are crisis stabilization centers where people can get treatment, not just somewhere to sleep things off for a few hours.

Kristian Foden-Vencil / OPB

No one was willing to take over the sobering center contract, “and there were a lot of reasons for that,” said Aaron Lones, a consultant hired by the city of Portland. “That old sobering center was not designed around these new street drugs.”

So a small group of people representing various behavioral health providers, Portland city government, and a few others began to look at ways Portland might be able to do a sobering center better.

In the year and half since, the group has swelled to include more than 160 individuals representing more than 80 organizations. They’ve been calling their vision the Behavioral Health Emergency Coordination Network, or the BHECN (“beacon”) project. Organizers have visited other stabilization center models, such as the Crisis Response Center in Tucson, Arizona. They’ve written up draft proposals and explored various approaches to sobering and stabilizing.

BHECN project members also conducted 26 one-on-one interviews with employees of the police bureau, ambulance service, sheriff’s department and county mental health mobile crisis response team.

“Meth appeared to be a major factor in the disposition of individuals being brought to jail or the ED,” a spokesperson for the mayor’s office, Shuly Wasserstrom, told The Lund Report.

Details of the project, however, have been slow in coming despite planning efforts that have cost nearly $2 million to date. By the end of August, the city will have paid Lones Consulting about $1.2 million, with CareOregon chipping in an additional $80,000, and Legacy Health has spent $486,000 on community engagement.

“This kind of thing has not happened in a long time in Portland,” Lones said. “We’re at a critical time in our history as a community, and we need answers, and the fact that the city and county and many many other organizations in the crisis system are focused [on this] - that doesn’t happen overnight. We’re dealing with a great deal of complexity.”

Contributing to the delay, the pandemic caused a one-year pause on planning. Then discussions stopped again while Portland and Multnomah County leadership hashed out who was going to oversee the project. On May 23, the city and county released a memorandum of understanding. It put Multnomah County in the driver’s seat, but in close consultation with the city, which was leading efforts initially.

“From the beginning of this project, we all set out to tackle a system that, to many on the outside, appears unfixable,” Portland Mayor Ted Wheeler announced with the release of the memorandum. “We are inspired by the power of everyone’s belief that this system is more than fixable, and that in BHECN, we have an opportunity to build an entirely new vision to serve some of the most vulnerable people in our community.”

The team developing the project has come up with a preliminary model and design, Skyler Brocker-Knapp, Senior Policy Advisor to Mayor Ted Wheeler, told The Lund Report. They’re sending the concept to providers in a request for information that will be released in the coming weeks and will start the conversations that lead to final design.

Doctors, people with a history of meth use and city and county officials are working together on the plans for a new "meth stabilization center," which have been delayed due to the pandemic. Some of the team is pictured here, posing while visiting the Tucson Crisis Receiving Center for research.

Photo Courtesy of Lones Consulting

The preliminary model, Brocker-Knapp said, “includes five-day observation, medically assisted treatment and stabilization for meth.”

Judge Nan Waller, who’s been deeply involved in discussions and presides over Multnomah County’s mental health court, said the plan all along has been to include services and resources for people suffering mental health and substance use crises that expand beyond meth.

“Every week I have somebody who’s in a crisis,” she said. “And I think, OK, now what do we do? I do not want to take somebody who’s in the middle of a mental health crisis into custody, but sometimes the behavior’s really concerning.”

She said when first responders take such a person to jail, the criminal justice system “gears up” and charges must be filed to hold them. A stabilization center would be an alternate way of getting people in crisis to safety, and ultimately reduce the criminalization of mental illness and substance use disorder.

“It gives me such hope that (the center) will be a door that is going to be more therapeutic. And, the jail would agree that they are often not the place where people should be when they are really in a mental health crisis,” Waller said.

Pace, focus prompts debate

Multnomah County Commissioner Sharon Meieran told The Lund Report that she supports the investment of time and money to tackle the problem. But things have moved way too slowly given the great need in the community. She became involved in the BHECN project early on.

“We need something yesterday,” Meieran said. “After these 19 months, over $1 million dollars spent by the city on a consultant, and that unquantifiable amount of time spent by so many people on this — we literally can’t answer the most basic of questions. … It is shocking to me that this is where we currently stand.”

Meieran, who also works as a Portland-area emergency room physician, said she knows how volatile these situations can be. Patients deep in a meth-induced psychosis, at their worst, “are scary, they are violent, they are screaming, they’re agitated, they need to be restrained. Sometimes it will take many people to be able to take care of one single individual … People get hurt, including the patients.”

Meieran said the delay over which agency should lead the project amounted to politics.

“The problem really started when this became a political issue and there was an unclear delineation of authority between the city and the county,” she said. “The conversations started happening behind closed doors; that’s when any progress seemed to stop. And that has been really unfortunate for our community, which needs this resource more than ever.”

She questioned the decision to narrow the focus of the center to just helping people on meth, when she said the problem is much bigger.

“When we started this process, we began with a great vision, with more enthusiasm and optimism and alignment than I’ve seen related to any community project — maybe ever,” Meieran said. “Everyone agreed from the get-go: We needed a place that would offer a higher clinical level of care for people undergoing acute detox, especially from meth, but also fentanyl, poly-substance abuse, people who are psychotic, agitated, violent and more.”

Ebony Clarke, who is now overseeing the project as Multnomah County’s Health Department director, said the need to narrow stemmed from the size of the problem.

“Because the effort is so robust, we have to start somewhere,” she said, adding that another reason starting small made sense is the lack of a clear funding source. “In terms of just what’s possible, in terms of funding, and just where we’re at, it was like, ‘OK, we got to narrow it.’”

Funding for planning is carved out in the county’s 2023 budget, but it’s still unknown where the funds to pay for the facility will come from.

Regardless of how the center materializes, it may take a while to see an impact.

For the past three years, Portland area emergency departments have averaged about 22,000 visits a year that were related to substance use, and a third of those were meth related.

“I don’t think we could build a facility large enough to make a huge, gigantic dent in that number immediately,” Henderson of Providence Oregon said. “But you got to pick a place where you’re going to at least start. And right now, the biggest gap that we have in the system is what happens after those first two days when you’re sober.”

This article was originally published by The Lund Report, an independent nonprofit news site covering health in Oregon.