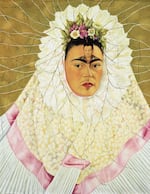

"Diego on my mind (Self-portrait as a Tehuana)," is one of the paintings in the exhibition, "Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera and Mexican Modernism," at the Portland Art Museum.

Portland Art Museum

The exhibition, “Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera and Mexican Modernism” launched last weekend at the Portland Art Museum. While Kahlo is a beloved icon for many, there has recently been growing criticism of the Mexican artist’s appropriation of indigenous cultures. Josie Lopez, head curator at the Albuquerque Museum, and Alberto McKelligan Hernandez, assistant professor of art history at Portland State University, join us to talk about artistic appropriation in the creation of a personal and national identity.

Note: This transcript was computer generated and edited by a volunteer:

Dave Miller: This is Think Out Loud on OPB, I’m Dave Miller. Fridamania continues. The Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera, and Mexican Modernism exhibit opened recently at the Portland Art Museum. It features over 150 paintings, photographs, and works on paper. The idea is to resituate Frida Kahlo, whose carefully curated identity has become almost omnipresent in contemporary culture, back into the artistic, social, and political world of post-revolution Mexico. And this traveling exhibit offers a great opportunity to talk about how personal and even national identities are crafted in the first place.

Joining me now are Josie Lopez, head curator at the Albuquerque Museum in New Mexico where this exhibit used to be, and Alberto McKelligan Hernandez joins us as well, assistant professor of Art History at Portland State University. It’s great to have both of you on Think Out Loud.

Josie Lopez: Thank you for having us.

Alberto McKelligan Hernandez: Thank you.

Miller: Alberto McKelligan Hernandez first, I thought we could start with questions of cultural appropriation, a very contemporary question, and we can talk about the challenges of applying it to something from 100 years ago. But in one of Frida Kahlo’s famous paintings, “Self Portrait as a Tehuana”, Kahlo painted herself as an indigenous woman from Tehuantepec. She said this to a magazine once: “I’ve never been to Tehuantepec, nor do I have any connection to the town, but of all Mexican dresses, it’s the one I liked the most, and that’s why I wear it.” If a non-native artist posted a similar photograph of themselves with similar reasoning on instagram today, they would be “canceled” immediately. We would call it cultural appropriation. How would it have been seen 100 years ago by people from Tehuantepec at that time?

McKelligan Hernandez: Well, first of all, thank you for having me, very happy to be here. I think what you mentioned, in terms of how it’s important to consider the specific historical/national context in which the imagery developed is of crucial importance here. When Kahlo was creating that painting, in which she presented herself wearing the traditional attire of the Tehuana, this was part of a larger national push to reevaluate the meaning and significance of indigenous culture in Mexico after the revolution, as a way to transcend the larger history of colonialism in the region. A lot of intellectuals, writers, visual artists were trying to insert indigenous imagery into their work as a way to celebrate that heritage, which had long been marginalized in Mexican culture and Mexican art. So, in terms of the original audience for those paintings, no one in post-revolutionary Mexico would have read the image as Kahlo presenting herself as a Tehuana. It would have immediately been understood as part of that political celebration of indigenous culture to transform the national identity of Mexico. So I think it’s important not to lose track of the larger structural conditions in which that imagery emerges. It’s very different from this kind of discourse of appropriation that makes it all about the individual choosing to profit, exploit imagery. An important part of the conversation loses track of that social context.

Miller: But it’s at least as interesting if not more that it’s not personal. And it still does seem though that, in this case, aspects of indigenous culture were being used by non-native people, non indigenous people, for their own ends. So what were the ends? What was the national identity that was partly being forged with aspects of indigenous culture?

McKelligan Hernandez: I think that’s a great question. An important part of this conversation is how racial difference, ethnic difference works in Mexico. It’s very different from the historical example of colonialism in the United States. Since the colonial period, during the colonial era in Mexico, there was this notion of mixtures or different racial types that were emerging, with the commingling of indigenous culture, Spanish culture, African culture. So there was a lot more fluidity in a way, in terms of how race, ethnicity was understood. After the revolution, as a way to unite all of these different racial groups, ethnic groups in Mexico, the rhetoric of mestizaje became the dominant framework in the country. The idea was that everyone in Mexico was part of the Mestizo race, everyone in Mexico had indigenous, Spanish, African culture within them. So we have the emergence of indigenous culture, but it’s really filtered or understood as part of the national heritage of mestizaje that was celebrated after the revolution.

Miller: That we’re all mixed, and we’re all in this together, and we’re all a part of this new country.

McKelligan Hernandez: That is correct. And of course, that’s part of the rhetoric of the post-revolutionary government as a way to unify the country, which was ravaged after the battles and violence of the revolution. And the egalitarian rhetoric and the celebratory narratives of the government did not quite match the day-to-day reality of indigenous people living in the country. But that was part of the cultural artistic push that was taking place at the time.

Kahlo’s image was part of that. In fact, she was not the only artist that was using the Tehuana as the symbol of Mexican identity, Mexican culture. Many intellectuals were specifically identifying the Tehuana women as the perfect symbol of Mexican national identity, because they were celebrated as a so-called matriarchal, female driven part of the country. There was this idea of how the Tehuana embodied everything that was powerful, important, even “magical” or “mystical” about traditional Mexican culture.

Miller: Josie Lopez, would Frida Kahlo have seen herself as being explicitly trying to create this new Mexican identity? Or would she have said “No, what I’m doing is more about my own understanding of my own identity, and I just so happened to be using the trappings of this new nationalist movement”?

Lopez: I think it’s a combination of both. One of the components that I really loved about being able to engage with and work on reorganizing this exhibition at the Albuquerque museum, because it has traveled to quite a few museums at this point, but one of the elements that I loved is putting Frida back into the context of Mexican modernism, which does incorporate many of the topics that Alberto was just talking about, whether you’re talking about national identity or the way that we think about race and the way that we think about colonialism, and specifically in Mexico’s colonial history and the way that it’s different in the United States. Also concepts of liberalism are very different in the United States than they are in Mexico. So, I think that putting Frida back into that context allows for a broader conversation about what it was that she was actually hoping to accomplish.

Her engagement with modernism at that time was very political. She was very much well known to be a communist. She and Diego Rivera were part of many artists in Mexico who were engaging with an international political discourse. One of the things that struck me in this process was really the dialogue between Frida creating her own identity, and make no mistake about it, that’s absolutely what she was doing. If you look at the way that she was photographed, the way that she was dressed, the way that she chose to present herself within the cultures of Mexico are very much intentional. But whether or not that identity that she was constructing within the context of Mexican modernism is ultimately what shapes the way that we see the commodification of Frida today all over the world, I think is a broader, bigger question, that maybe allows for a little bit of a nuanced approach to thinking about those contemporary discussions about cultural appropriation.

And obviously, I agree with Roberto that that having an understanding of the context of the indigenous figure in the post-revolutionary Mexican period, I do think there’s room there to also think about how identity was looking to a quintessentially Mexican antiquity as it was embedded in an indigenous culture, but it wasn’t necessarily acknowledging the everyday lives of the indigenous people in Mexico. And so I think there’s definitely room for discussion of how Frida was both creating, but also benefiting from, that broader view of what it meant to be Mexican.

Miller: I’m curious, Josie Lopez, how you make sense of the ways in which Frida Kahlo has become such a marketable commodity, on lunch boxes and pillows and coffee mugs and face masks, so people can sort of almost embody Frida Kahlo’s face as they try not to get COVID walking around? What is it about Frida, you think, that has so many different people feel such a deep connection to her, and also want to show it commercially?

Lopez: It’s fascinating because, as I said in the exhibition, there are other artists like María Izquierdo for example, who at the time was actually much more famous than Frida. If you look at old newspaper articles that were written in the 1930s, she was referred to as Mrs. Rivera. And so the difference in the way that Frida is looked at I think has a lot to do with her personal story. And in talking with other Latinos in particular, people connect to this personal struggle that she had to endure for much of her life, whether it was her relationship with Diego, or whether it was her own physical ailments, and really having to grapple with with her body failing her for much of her life. And so I think it’s that personal story that people connect to, that really makes our own stories relate to her in a different way.

I think that that’s very different though from what the identity was that existed for Frida at the time, because as I said, she was engaged in these incredible activist political examinations of capitalism and communism, and what was happening in the world, and all of that was embedded in an artistic practice that, for her, as well as the other Mexican artists at the time, actually provided them a sense of agency. As the Mexican government ultimately co-ops essentially the Mexican mural movement to become this sort of nationalized message of Mexican national identity, it’s fascinating to see that that level of discourse was happening. So there’s just this incredible juxtaposition between the moment in which Frida was living, and how that has become romanticized. And I think for many of us, it’s that kind of universal and specific that allows her image, her artwork, and her personal story to have resonance over time.

Miller: Alberto, let’s turn to the people who aren’t named Frida Kahlo for a second, because because Josie was making an important point there, and actually Josie, I heard you say in an earlier podcast interview that it was almost as if you could use the fact that people are going to see an exhibit about Frida Kahlo, to get them to see other works from other artists they may not have been aware of.

So Alberto first, who are the artists you think have gotten short shrift because people like Frida Kahlo, or maybe Frida Kahlo in particular, has gotten so much attention? Who do you want folks to also know about?

McKelligan Hernandez: I think that’s a great question that I grapple with on my day-to-day work, actually. I teach a class on Latin American women artists at Portland State University. And the first day of class, I show an image of Kahlo’s work, and I go on this long discussion of “you all know this one artist, we’re going to spend the rest of the quarter talking about all of these other amazing artists that were in Mexico and Cuba and Argentina.” There were other women artists, I think specifically Josie already mentioned one of the artists that I find more interesting to think about, Maria Izquierdo, also a woman artist working in post-revolutionary Mexico. Like Kahlo, she used very personal imagery at times. She used traditional Mexican iconography to create these really elaborate and dense allusions to politics, women’s social position in Mexico after the revolution. Another artist that I think viewers should definitely look for during the exhibition as they walk through it is the work of Lola Alvarez Bravo. She has a similar history to Frida Kahlo in that during her lifetime, or even now, she is commonly referred as the companion, one-time wife of Manuel Alvarez Bravo, who is considered the father of Mexican photography. But her work is a really interesting exploration of indigenous identity. She made these amazing photo montages that were very much inspired by the Soviet avant-garde. She employed this format that was known as a photo mural for private buildings, government buildings, that really considered the ways in which Mexico was becoming a modern, industrialized nation after the revolution. And there’s a few interesting examples of that in the exhibition.

I think even just the title of the exhibition points to how it wasn’t just Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo that were working, but it was really a large-scale, aesthetic, political, social revolution that was happening in Mexico. And even it wasn’t just one modernism that was developing, it was really several competing, contentious modernisms that we’re developing in Mexico after the revolution.

Contact “Think Out Loud®”

If you’d like to comment on any of the topics in this show, or suggest a topic of your own, please get in touch with us on Facebook or Twitter, send an email to thinkoutloud@opb.org, or you can leave a voicemail for us at 503-293-1983. The call-in phone number during the noon hour is 888-665-5865.