On the evening of May 29, gunfire echoed across a North Portland shopping plaza.

Around 6:30 p.m, an armed security guard on patrol at Delta Park Center fatally shot Freddy Nelson Jr., 49, four times through the windshield of Nelson’s Nissan Frontier as he sat in the plaza’s parking lot, according to interviews with eyewitnesses and family members.

Records show the shooter, identified by OPB as 28-year-old Logan Gimbel, was one of at least three guards working for Cornerstone Security Group, a company that states it only provides armed security, who did not have a license to carry a gun while on the job.

The bullets pierced Nelson’s head, heart and both of his lungs, according to his father, who has spoken with detectives and a victim advocate from the Multnomah County District Attorney’s office. Witnesses said Nelson’s wife, who was sitting in the passenger seat, jumped out of the vehicle at the last shot with her shirt drenched in blood and pepper spray, screaming at the guard, “You killed my husband.”

In a city plagued with a skyrocketing number of shootings, Nelson’s death — the 37th homicide this year and the second that day — faded almost immediately from public attention. Unlike the two fatal shootings by Portland police officers this year, Nelson’s death has received no media scrutiny and triggered little public outrage.

Yet, his death serves as a case study for another notable law enforcement problem the city is grappling with: powerful business interests turning to private security to do the work of police officers, enabling them to wield force against vulnerable Portlanders with a fraction of the oversight.

TMT Development, one of the city’s biggest real estate companies, had contracted with Cornerstone Security Group to patrol the Delta Park Center for more than a year. In the spring of 2020, Vanessa Sturgeon, CEO of the company and a board member of the influential Portland Business Alliance, asked the guards to police the crowds converging on the plaza’s BottleDrop, one of the few locations open at the time where people could recycle empty bottles and cans for cash. The company said the security was necessary, in part, because the long, sometimes unruly lines weaving across the shopping center posed a public health threat in the middle of the pandemic.

Related: After Campus Murder, Kaylee's Law Would Limit Security Guard Powers

Over objections from BottleDrop management, TMT Development asked the armed guards to bring order to the crowd. The guards kept the line short near the BottleDrop and held the rest of the customers at bay on North Hayden Meadows Drive on the other side of the parking lot, roughly 350 feet away.

It didn’t take long for customers to start chafing against the restrictions imposed by security personnel with Cornerstone. Five patrons interviewed by OPB describe the guards as caustic and callous as they enforced the line regulations on some of the city’s poorest residents. For many Portlanders in dire need of quick cash, the BottleDrop was a lifeline during the pandemic, providing a streamlined way to collect the refund value on discarded bottles and cans.

The Oregon Beverage Recycling Cooperative, which oversees the city’s various BottleDrop locations, also appeared to quickly have problems with Cornerstone’s performance after agreeing to pay for a guard. In May 2020, after two guards detained a man leaving the BottleDrop’s bathroom, the co-op stopped paying for Cornerstone security, according to a complaint they filed with the Oregon Department of Public Safety Standards and Training. (Typically, the hourly cost for these guards can range from $45-$65 per person.)

But TMT Development continued to contract with Cornerstone. The guards kept patrolling the plaza as well as the BottleDrop line — until Gimbel shot Nelson, a BottleDrop regular. Two shopping center workers told OPB that they have not seen Cornerstone guards in the area since soon after the shooting.

Robert Steele, one of the directors of Cornerstone Security Group, declined to comment for this story. Portland police said they’re still investigating and could not update the public beyond a 100-word release pushed out three days after the shooting. The release identified Nelson and his cause of death, but did not provide the security officer’s name. OPB was able to identify Gimbel through records on the shooting kept by DPSST.

Nelson’s family said they are still missing massive chunks of the puzzle as they wait to find out if Gimbel will be charged for the killing: Namely, what caused the guard to approach the car and fire four bullets into a vehicle of a Delta Park regular, who they said was unarmed?

“They just shouldn’t have guns,” said Freddy Nelson Sr., who drove to Portland from his home in Wyoming the day after his son was killed. “Especially these guys when they’ve already had problems over there. ... It was a time bomb waiting to happen.”

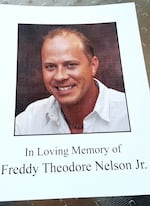

The funeral program for Freddy Nelson, who was fatally shot by an armed guard near the Delta Park Center BottleDrop, May 29, 2021. The guard was an employee of Cornerstone Security Group, a company hired by the real estate company TMT Development to patrol the shopping center.

Courtesy of the Nelson family

The shooting

The family of Freddy Nelson Jr. remembers him as a natural entrepreneur. He owned a real estate company in Colorado and a used furniture store in Wyoming. When Nelson returned to the Portland area roughly nine years ago, his family said he made his money as a handyman with a few side hustles to bring in extra cash — including collecting recyclables and selling discarded pallets.

This made Nelson a familiar face within the Delta Park Center. Lowe’s employees knew him on a first-name basis and let him collect old pallets from behind the store, which he sold to companies that wanted the wood. Every so often, Nelson would stop by the BottleDrop next door with bags of empties, his family said.

At the time of the shooting, Nelson lived less than two minutes from Delta Park Center, in one of the 15-or-so recreational vehicles lining North Kerby Avenue.

On the evening of May 29, he drove over with his wife Kari Nelson, who declined to be interviewed for this story through her sister. The couple was shopping that evening for supplies at Lowe’s for a bus they were remodeling, according to the oldest of their three sons, Kiono.

It remains unclear why Gimbel approached the couple in the parking lot. Two current Cornerstone guards, who requested anonymity to speak about their employer, said Nelson was well-known within the company. They believed Gimbel approached the car because Nelson had been “trespassed” from Delta Park for dealing drugs on the property, meaning he was on a list of people banned from the center. One of the guards believed there had been reports of a domestic disturbance. OPB could not independently confirm either of these statements by the Cornerstone guards.

Court records show Kari Nelson filed for a restraining order against her husband in July 2019, though the order was never successfully served on him, according to a state public information analyst. Two-and-a-half weeks after she filed for the order, Nelson Jr. was arraigned on multiple charges, including a felony burglary charge and fourth-degree assault against his wife. A judge then ordered Nelson not to contact his wife. That order expired after the charges were dismissed in July of 2020. Nelson Jr. had other recent run-ins with the law, including misdemeanor assault and menacing charges.

City officials declined to release recordings of the 911 calls from the shooting due to the ongoing investigation. The body camera Gimbel was wearing at the time has been turned over to police, according to records kept by DPSST. The Multnomah County District Attorney’s Office said they are reviewing the investigation, which police turned over Wednesday.

Attorney Tom D’Amore, who has spoken with Kari Nelson and is representing the family as they consider litigation, has the most detailed account offered publicly to date: He said an armed guard approached the couple in the parking lot that night and told Freddy Nelson to put his hands behind his back. D’Amore said Nelson had a strained relationship with the Cornerstone guards, who allegedly followed him when he was on the property. Nelson reportedly refused the order, instead getting inside his truck. According to D’Amore, Gimbel stuck his arm in the rolled-down back window of the vehicle and pepper-sprayed the couple.

Gimbel then reportedly moved in front of the vehicle and fired four shots through the windshield. D’Amore said the couple had not been fighting at the time, and he did not know why the guard approached.

“There was no physical altercation whatsoever on their part,” D’Amore said.

Under Oregon law, private security guards have the same ability to detain a person as any other citizen. If they have probable cause to believe a crime has been committed in their presence, they can make a “citizen’s arrest” and temporarily prevent the person from leaving until law enforcement arrives. They may use force “reasonably believed to be necessary” to defend themselves, protect property, prevent a criminal trespass or make a citizen’s arrest.

According to DPSST records requested by OPB, Gimbel took the training to work as an armed guard around the time he started at Cornerstone in September 2020. But the state never received his application to be licensed to work with a gun.

Gimbel did not respond to repeated requests for comment. According to notes kept by DPSST on the shooting, one of the owners of Cornerstone told the agency that Gimbel had “prior issues with the victim” and acted in self-defense, firing the four shots after Nelson “acted as though he was going to run over Gimbel with his car.”

Two eyewitnesses questioned that account, saying the vehicle never moved out of the parking space.

“As far as I could tell, when the guy was shot through his windshield, the car had not moved out of the parking spot,” said a Lowe’s employee, who estimated he was about 10 to 15 car lengths away from the shooting. “The car was not outside the parking spot. He wasn’t trying to go anywhere. He was just trying to tell the officer, ‘Hey I’m going to leave.’”

The worker, who asked not to be identified because Lowe’s employees are not supposed to speak with reporters, said he came out to the parking lot from inside the store after he heard screaming. He said he made it there in time to hear the guard yell, “If you don’t yield to me, I’m going to shoot,” followed by multiple shots. He said the interaction he overheard lasted less than a minute.

The employee, who said he had not spoken to police, believed that Nelson’s truck was not running at the time of the shooting. Samuel Kisner, who was inside his car parked three or four spaces away from Nelson, said he couldn’t be sure whether the vehicle’s engine was on.

Kisner arrived in the Lowe’s parking lot just as Gimbel was pointing his gun at Nelson’s truck.

He said a security patrol car was blocking Nelson’s vehicle from leaving, parked horizontally six or seven feet away from Nelson’s truck. Kisner said he heard Gimbel warn that he was going to shoot if Nelson moved. He said Nelson’s truck moved slightly toward Gimbel, at most three inches, and Gimbel fired.

Kisner, who said he owned a private security firm in Florida and had himself pulled his gun while on the job, called the killing unjustifiable.

‘It was a matter of time’

The warning signs that Cornerstone guards and BottleDrop patrons could be a combustible mix appeared early.

Jules Bailey, the chief stewardship officer of Oregon Beverage Recycling Cooperative, which operates the BottleDrop location, sounded alarm bells before the guards even arrived. Willamette Week reported in March last year that Bailey protested the proposal for armed guards, predicting “an unintentionally violent confrontation” in an email sent to Sturgeon, the head of TMT Development. Bailey recently joined the board of the Portland Business Alliance.

Sturgeon contended the guards, who she already contracted with to patrol the plaza, were necessary to tame crowds that had grown during the pandemic while many grocery stores closed their bottle return centers due to health concerns. Other businesses in the shopping center had complained about the crowds, per Willamette Week.

In addition to the BottleDrop, Delta Park Center is home to several big box stores including Lowe’s, Dick’s Sporting Goods and Wal-Mart. TMT Development owns the center, as well as a host of prominent properties across the city including two of downtown’s tallest buildings — Park Avenue West and Fox Tower.

Reached by phone, Sturgeon declined to comment on the shooting or elaborate on why she wanted the guards, citing an ongoing police investigation. Sturgeon’s press liaison also did not provide answers to a list of questions, including what backgrounding took place before hiring Cornerstone and whether the guards work at other TMT-owned properties.

A complaint filed with DPSST by the Oregon Beverage Recycling Cooperative shows the BottleDrop ultimately agreed to pay for one guard that TMT Development wanted from Cornerstone — but terminated their contract within a few months.

The impetus came on May 5, 2020. In a DPSST complaint, Bailey alleged that two Cornerstone guards — later identified as John Harris and Robert Steele — followed a man into the BottleDrop, waited until he left the restroom, and then escorted him out, each holding an arm, “in a type of control or escort hold.” Bailey said he believed the guards had no right to detain the man.

“I’m concerned that at minimum, the conduct of the Private Security Professionals and Cornerstone Security Group was excessive and unnecessary, and at most, may have been in violation of ORS 133.225,” wrote Bailey, citing state law around citizen’s arrests.

DPSST found the complaint unsubstantiated, stating the guards followed the man into the store because he had been masturbating outside and he was not a customer of the BottleDrop. TMT Development continued to contract with Cornerstone to manage the lines outside after the incident.

According to its website, Cornerstone Security Group was founded in 2017, “on the principle of reinventing the security industry in the State of Oregon and abroad.” DPSST records show the company employs about 45 security guards, who have worked at various apartment buildings, businesses, shopping centers, and at least one synagogue. Their website states the company “will not do Unarmed Security in any capacity.”

Two former Cornerstone guards, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, said it was hardly a secret that some armed security was performed by guards who were not certified to carry a gun. To find out if a guard is properly licensed to carry a gun, they said, a manager would simply need to plug the name into a state database. The two guards said Cornerstone took a lax approach to certification.

“They basically say that you’re a big boy … saying, ‘we trust you enough to do it yourself and not hassle you down,’” said an employee who quit this spring because he felt his supervisor was behaving inappropriately toward lower-level employees. “I don’t know how DPSST hasn’t caught on yet.”

The state agency did appear to catch on shortly after Nelson was killed. Soon after Cornerstone notified regulators about the shooting, DPSST began the process of revoking Gimbel’s license.

Gimbel told the state that his application for a license to carry a gun got lost in the mail and he forgot to follow up, according to the agency’s case file on Gimbel. A regulator responded that it was Gimbel’s responsibility to make sure the application was processed. Gimbel voluntarily surrendered his security guard license three weeks after the shooting.

“This seems like a failure on both our parts. Mine for failing to check the status and yours for failing to notify members that forms sent the ass end of 2020 could be lost,” Gimbel told the state in a hand-written note processed June 22 giving up his license. “Have a nice day.”

After the shooting, one of the company’s owners, Matthew Cady, called a compliance specialist with DPSST and said he had discovered two additional employees who were working without a license. He did not give the state their names, but told the agency he was working on getting them certified to work with a gun.

The Delta Park Center BottleDrop location nearwhere an armed guard fatally shot Freddy Nelson, a bottle drop regular, on May 29, 2021. The guard was an employee of Cornerstone Security Group, a company hired by the real estate company TMT Development to manage the crowd of folks lining up to recycle empty bottles and cans for cash.

Rebecca Ellis / OPB

Cornerstone culture

A deeper dive into the company reveals other warning signs that the guards may have been ill-prepared to safely manage a crowd that included some of the city’s most vulnerable and impoverished people.

BottleDrop patrons said tensions often ran high during the pandemic, as customers, heavy with garbage bags and shopping carts of empties, sometimes had to wait for the better part of a day in a line hundreds of people long. Three former guards said the company offered no de-escalation training, and banked on the guards, many of whom had military or law enforcement backgrounds, to know from prior experience how to defuse a tense encounter.

“There was no actual tactical communications training,” said a former employee, who left this summer. “They just expect people to know how to do it when they got there.”

Some BottleDrop customers said this was clear to anyone who spent time in the line.

“It was a matter of time, I felt. These guys all have ego complexes, and they love to add to the strife of this already fucked up situation,” said Skylarr Thomas-Miller, 35, who does landscaping and roofing work and said he stops by the BottleDrop two or three times a week.

One instance stuck out to Thomas-Miller. Last winter, he said he believed the guards were messing with an older Black man out of boredom, first telling the man to head toward the BottleDrop, and then, when he got there, telling him to turn back to the line on Hayden Meadows Drive. Thomas-Miller said he stepped in and asked why the man, bogged down with two black contractor bags brimming with containers, couldn’t wait by the BottleDrop and avoid lugging the bags across the parking lot. He said the security guards told him he was creating a conflict.

“These guys don’t seem like any of them have ever had mental illness training or dealings with at-risk populations,” Thomas-Miller said.

Cornerstone Security did not respond to emailed inquiries into what training their guards receive and if they’ve taken steps to ensure guards are properly licensed to carry firearms. Reached by phone, Robert Steele, a director at Cornerstone, declined to comment for the story due to the ongoing police investigation and politely warned he would be disconnecting the call.

Six former and one current employee said they felt upper-level management at Cornerstone tolerated a toxic workplace, where managers routinely made offensive jokes and sexual harassment was a regular occurrence against the few female employees.

Andrew Grabhorn, one of Cornerstone’s first employees, said he felt the culture at the company, which he described as violent and unprofessional, descended from the top.

Grabhorn, who said he was with Cornerstone for three years starting as a patrol guard and ending as an on-shift supervisor, said he quit in February 2020, in part, because he felt the co-owner, Cady, glorified violence. Grabhorn said he remembers sitting in the passenger seat of Cady’s patrol car sometime in early 2019 when the owner turned to him and asked if he knew what a “K-party” was. Grabhorn said he did not.

“He said, ‘It’s a party your buddies throw you after you get your first kill — I can’t wait for mine,’” Grabhorn recalled.

Cady, one of three men listed on Cornerstone’s business registry, did not respond to an email, text, two phone calls, and a Facebook message. Within half-an-hour of OPB reaching out, he made his account private.

On social media, Cady often espouses radical far-right political views. In the last few months, Cady, has taken to Facebook to refute that President Joe Biden won the presidential election, deride trans and homeless people, compare vaccine requirements to the Holocaust, and reject the idea that masks prevent the spread of COVID-19.

Another co-owner, Jeffrey James, currently has a professional standards case against him with DPSST, initiated four days before Nelson was killed. The agency opens these cases when they receive information indicating an officer violated their standards — this could mean the officer had a complaint filed against them, provided false information or received a criminal citation, among other reasons. It’s unclear why the agency initiated a case against James.

A police report shows James was involved in an incident in 2019 in which an ambulance was called to the Tigard Plaza Shopping Center after James and Cady approached a homeless woman who had been recently barred from the property. According to the report, on April 29, 2019, James told Tigard police he pushed a woman that the guards were physically escorting off the property after she lunged at him and he felt “an imminent threat of being stabbed.” An eyewitness told police the guards “tackled” the woman, who the report stated was lying on the sidewalk in handcuffs when the police arrived, “volatile, upset and screaming.” An ambulance from Metro West was dispatched, though it’s not clear from the report what her injuries were. The medical information in the report was redacted.

At least one other Cornerstone manager has extremist affiliations. Harris, the Cornerstone director who restrained the man exiting the BottleDrop bathroom, confirmed he was near Sugar Pine Mine in Southern Oregon in 2015, when heavily armed anti-government extremists flocked to the mine near Merlin, Oregon, to defend the mine from an alleged incursion by the Bureau of Land Management.

Harris said he had been hired as an instructor by the people at the mine many times and asked to consult on their operations, but emphasized he does not participate in militia activity and viewed the training purely as a business transaction.

Grabhorn said he believed that the killing of Nelson, who he remembered as reasonable as long as the guard didn’t act like an “egotistical asshole,” could be traced back to a hyper-masculine, overly-aggressive workplace culture created by Cornerstone’s leaders.

“The whole way this shooting occurred, I just can’t fathom,” he said. “I believe it all happened from a point of ego. Our industry’s not meant to be ego. You’re supposed to conduct yourself with honor and integrity, and Cornerstone always fell short of that.”

A sign at the Delta Park Center BottleDrop location where an armed guard fatally shot Freddy Nelson, a bottle drop regular, on May 29, 2021. The guard was an employee of Cornerstone Security Group, a company hired by the real estate company TMT Development to manage the crowd of folks lining up to recycle empty bottles and cans for cash.

Rebecca Ellis / OPB

Bigger picture

Benjamin Donlon, a member of the homeless advocacy group the Western Regional Advocacy Project, can easily rattle off the various private security companies that patrol different sections of Portland. His list includes G4S Secure Solutions, which guards Portland City Hall; Portland Patrol Inc, which contracts with the Portland Business Alliance; and Echelon Protective Services, which does private security for hotels and businesses downtown. As of October 2020, Echelon was working with 25 downtown locations, according to a “notice of exclusion” Donlon sent to OPB that includes a map of Echelon’s contracted properties.

Donlon has been tracking the use of private security in Portland for years, watching as a fast-growing, under-regulated industry increasingly encroaches on semi-public spaces.

He said he believes these guards are a threat to the city’s homeless population, able to displace people from semi-public spaces such as parking lots and doorways with little oversight from city officials.

“Unleashing hordes of unaccountable privatized forces that work for specific interests to patrol public space — it just doesn’t seem like a great idea in the long run,” he said.

Donlon helped spearhead a city audit last year of Portland’s own “enhanced services districts.” In these districts, businesses pay for extra services, including additional security and policing services. The oldest and largest, Downtown Clean & Safe, contracts with the Portland Police and Portland Patrol Inc. for guards, some of whom are armed, to secure 213 blocks downtown. That district is run by the Portland Business Alliance.

The audit was highly critical of the city’s hands-off approach to these business districts and found private security officers were regularly circumventing city oversight as a result. According to the audit, the city had not reviewed the reports the Downtown Clean & Safe district was supposed to keep on complaints initiated against guards by the public. Auditors warned of “disparate law enforcement outcomes” if the city didn’t change its tack.

The downtown guards are making their way onto the radar of the Portland City Council.

The city is in the middle of negotiating a new contract with Downtown Clean & Safe as the old one expires at the end of September. One of the potential sticking points: Will the city continue to allow its wealthiest business district to pay for armed guards?

At this point, the City Council hasn’t decided. Commissioner Jo Ann Hardesty has been outspoken that she does not want guards with guns patrolling downtown, and Commissioner Carmen Rubio said she “has concerns.” Commissioner Mingus Mapps said he’d “advise against” it, but doesn’t think it’s council’s place to prohibit armed security. Commissioner Dan Ryan’s office also did not take a stance, but noted many Portlanders want to see private security companies cut back on the use of firearms. Portland Mayor Ted Wheeler did not respond to the inquiry.

At least one private security company is seeing its footprint in Portland shrink. According to multiple guards, TMT Development no longer contracts with Cornerstone. Workers at the shopping center said Cornerstone guards did not show up the morning after Nelson was killed.

A new private security company, Talon, now patrols Delta Park Center and the line outside the BottleDrop.

All are armed.