An artist’s depiction of the Machairodus lahayishupup eating Hemiauchenia, a camel relative. The image is part of a mural of the Rattlesnake Formation of Central Oregon, where fossils of the newly identified feline species have been found. The mural is exhibited at John Day Fossil Beds National Monument, part of the National Park Service.

Roger Witter

The recent naming of a saber-toothed cat species in the words of Oregon’s Cayuse people shows how languages considered extinct remain relevant today, and highlights the role that Indigenous cultures can play in paleontology.

There are no longer any fluent Cayuse speakers and only a few records that document the language. But using Cayuse words to label the giant feline — one of the largest ever discovered — shows that the life of a language is not limited to its inclusion in a large dictionary or volume of text, said linguist Phillip Cash Cash, Cayuse-Nez Perce.

Naming the big cat in the language of the Cayuse people, who are now part of the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, “gives the community an identity and recognizes the contributions of early generations of Cayuse people,” said Cash Cash, who works as a consultant for the tribal government. “It’s a way to honor those ancestors who originally spoke the language.”

Fossils of the massive feline were found in the 1950s on ancestral Weyíiletpuu (the name for Cayuse people in the Nez Perce language they later adopted) lands in today’s eastern Oregon, where the cat shared the earth with giant camels and giant sloths five to nine million years ago. Scientists only recently identified the fossils as a new species.

The full name of the new cat is Machairodus lahayishupup.

Cash Cash, who taught linguistics for 10 years at the University of Arizona, took on the task of finding a Cayuse name for the cat, searching through documents of the original language, looking for “any correlation to cat or cat species.”

He was able to compare Cayuse words from the earliest Smithsonian records in 1829 with later documents from 1888 containing similarities that allowed him to reconstruct a name.

The genus Machairodus comes from the Greek and Latin words for “dagger tooth.” The Cayuse words Lahayis Hupup (pronounced Leh-HIGH-ees-hoop-oop), translate to “ancient wild cat” or “old wild cat.” Taken together the full species name roughly translates to “ancient wild cat with dagger teeth.”

A ceremonial naming, a common tribal celebration in which a name in the Native/Indigenous language is given to an eligible tribal member, will be scheduled when COVID-19 protocols are eased for the community.

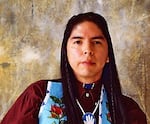

Phillip Cash Cash, an enrolled member of the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, is a linguist who taught for 10 years at the University of Arizona.

Alyce Sadongel

“A cat species, as an elder would think of it, is not without purpose,” said Cash Cash. “It’s almost as if a new kind of being has appeared in our land. A naming ceremony would grant it an identity and validate the name in a cultural way.”

Decades in the Making

The first Machairodus lahayishupup fossils were found in 1959 near McKay Reservoir between Pendleton and Pilot Rock. But it would be decades before anyone realized the fossils came from a previously unnamed species of prehistoric cat. John Orcutt, now an assistant professor of biology at Gonzaga University, came across them in 2008 at the Museum of Natural and Cultural History in Eugene, while working on his doctorate at the University of Oregon. Orcutt, whose focus was on climate change and mammal evolution, said he kept the unusually large arm bone “on the back burner” as he finished his doctorate. He eventually collaborated with Jonathan Calede, assistant professor of evolution, ecology, and organismal biology at Ohio State University, to identify the cat. Their study was published in May in the Journal of Mammalian Evolution.

The largest of the seven Machairodus lahayishupup arm fossils available for the analysis was more than 18 inches long and nearly two inches in diameter. By comparison, the average modern adult male lion’s arm is about 13 inches long. In adulthood, the Machairodus lahayishupup probably weighed between 600 and 900 pounds, more than four times the size of a mountain lion.

The scientists believe the cat was an ambush predator and a relative of the celebrated saber-toothed cat Smilodon, the famous fossil found in the La Brea Tar Pits in California. Smilodon went extinct about 10,000 years ago.

Orcutt and Calede determined that Machairodus lahayishupup lived in North America, as well as Europe, Asia, and Africa, but the largest concentration of those fossils, as well as the best preserved and most impressive, are from northeast Oregon on traditional Cayuse lands.

In March, having determined that a new species had indeed been found, Calede and Orcutt reached out to staff at Tamastslikt (Tah-MAHST-slickt) Cultural Institute on the Umatilla Indian Reservation in Eastern Oregon.

Since the 18th century, the norm has been to name new species using Greek or Latin, “but this cat didn’t live in Italy or Greece, and we wanted to give it a name in a language indigenous to the landscape in which it did live,” Orcutt said.

Working with Indigenous institutions like the Tamastslikt Cultural Institute, he said, is a way for paleontologists “to recognize the importance of that context and of including Indigenous voices in our field.”

“It means a lot to me to be able to collaborate with the tribes on whose traditional lands I do my field work and to be able to give this amazing animal a name with real local significance, rather than some phrase from the dead European language,” Orcutt wrote in an email. “On a larger scale, I think and certainly hope that this name is just one part of a larger pattern in our field of recognizing that the fossils we study come — unless you’re working in Antarctica — from someone’s native land.”

“Science names the world,” Cash Cash said. “Indigenous knowledge can make a contribution, even when it isn’t cataloged or documented, and that is profound. I think the opportunity exists for Indigenous groups to make contributions in this way. … It provides a rare opportunity not just for paleontology, but for the world of tribal people as well. To name it in the way we did allows us to express ourselves and be who we are.”

‘Extinct’ or ‘dormant’?

The Cayuse language was an isolate that had no words and speech patterns in common with other Northwest languages. Its last fluent speakers died in the 1940s. Over time, the Cayuse people started speaking Nez Perce.

Tribal dictionaries contain no more than 400 Cayuse words, said Bobbie Conner, director at Tamastslikt. However, some old Cayuse words are still used to describe places, and tribal members still carry Cayuse names.

“Naming the cat is an opportunity for us to keep the Cayuse language alive, but it also recognizes fossils collected from our homeland over six decades ago still have stories to be discovered,” Conner said.

Cash Cash, who prefers the term “dormant” to “extinct,” said the language will never be revived, but it also hasn’t faded away.

“The ability to use what is in these sparse records really is astonishing when you think about it, because Cayuse language has been classified as extinct for quite a long time,” Cash Cash said.

Connecting the Cayuse language to ancient history “is its own kind of blessing” because it sustains the language and “also ties us to the ancientness and the landscape of our past,” Conner said.

“This is a unique opportunity to make the world aware of not only the fossil, but of the language,” she added.

Said Cash Cash, “Even if you are alone and speaking without another person present, the words still have meaning and the words still are heard by the world around us. It’s kind of like the elders tell us that names echo across the earth and when they echo across the earth, the earth receives that and recognizes that those names are being spoken. So, the land and earth hears when we speak the language.”

“It comes down to a speaker uttering the words of a language,” he added. “The real value, at least in the perspective of our community, is that the cat species found and identified is in and of itself saying the language is alive in some way. It isn’t extinct. As our elders say, ‘The language hasn’t faded away.’”