Activist and photographer Richard Brown has long been on the frontlines of Portland’s evolution. Among other things, he’s worked to bridge the divide between law enforcement and the Black community.

Brown grew up in 1940s Harlem where it wasn’t uncommon to see a famous person walking through the neighborhood. As a youth, he would wondered what life was like outside of the brownstones that he was accustomed to. He would spend time collecting stamps and looking at picture books which helped to fuel his imagination. Later he received his first camera, which gave him a chance to document these experiences himself. At 17, Brown joined the Air Force, which gave him the chance to travel the world. After retirement, Brown made his way to the west coast and Portland became his home.

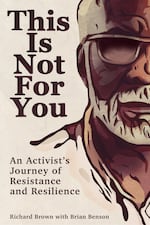

Now Brown has written a memoir: “This Is Not For You: An Activist’s Journey of Resistance and Resilience.” Richard Brown sat down with OPB’s Paul Marshall recently to talk about his own journey.

Paul Marshall: What was your impression of Portland’s Black community when you came here?

Richard Brown: There weren’t very many of us, that was the thing that really stood out. One of the things that I had heard about Portland was how friendly it was, and I guess I didn’t think that when I got here.

When I got here, I was retired and didn’t want to do anything. I was ready for whatever was dumped in my lap. I was ready to be wherever I was.

I had met a lot of people in the service who always were someplace that they hated and never wanted to go back to and couldn’t wait to leave. And I thought well that’s not a very good way to approach life

So I committed to anywhere, I was going to make a good time out of it and I was able to do that. Although it was concentrated the absence of Black folks was real obvious for to me

Marshall: You talk a lot about your work to bridge the divide between the Black community and the police. Was it easier to do that while being a photographer? And were there moments that you were able to find solutions to fix that divide?

Brown: When I came here, I didn’t want to get involved in anything. You go to these rallies, you go to these meetings and pretty soon you find yourself involved working on projects. But the photography allowed me to meet all of these folks because I was a photographer at the Observer. I was all over the city covering little things that time didn’t mean anything. It exposed me to people I probably wouldn’t have met, exposed me to issues I probably wouldn’t have gotten involved in,

It’s only when I sit down and think about the things that I’ve been involved in, that I become overwhelmed. There’s not a lot of places where that could happen. It’s easier, I think, to be an activist here, but it may not be as challenging because stuff is just slow. You know, you’ve got to convince people that things have to change.. Nobody wakes up in the morning and says: “Oh, Black folks aren’t being treated well here. We gotta do something about that.” Nobody thinks about that. You got to keep beating at that door.

Marshall: Being a Black photographer in the space. What power did the camera symbolize to you?

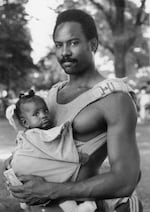

Brown: It allowed me to portray Black folks in a way that you normally don’t see. In the Oregonian, you hardly ever see a Black person in the obituaries. It’s almost like Black folks don’t die here. The image of Black folks has always got some negative connotations attached to it. And the photography allowed me to show Black folks doing positive things, interacting in positive ways, being loving to each other, helping each other, being a community to each other. That’s what I got out of photography.

Richard Brown

Marshall: In addition to your work as a photographer, you are an activist. There was a moment in the book where Portland Public Schools agreed to stop forced busing, but they said that they were going to open a school and community named it after Harriet Tubman. At some point, they decided to not move forward with Tubman. There were meetings where people were speaking out voicing their concerns. During one of the meetings, you were there as a photographer. There was a moment where you did, kind of step off the wall and you did speak, Was that a moment for you that you came to grips with your world as a photographer and an activist - they’ll always merge and it won’t really be separate?

Brown: I’d go to the meetings and I would purposely stay out of things. Stay out of getting involved, But, you know, sometimes you’re in a situation and it’s obvious that something isn’t being said. It could be because people don’t know it could be because somebody forgot, but you think it’s important, and that’s what that moment was.

You meet people and you see how committed people are to these things happening. You feel that you at least got to say something to be a part of that movement. You got to remind people that this is something that impacts me also.

Marshall: You also talk about over the time Black neighborhoods became gentrified and how unsettling it was. So when did you start to see that change more visibly?

Brown: The gentrification is something that I’ve witnessed all over this country. So I knew what the signs were. I learned how it happened here and it mimicked the way it happens everywhere else. The community is allowed to go to pot and nobody cares about it. Then some businessman/ businesswoman decides, it’s time to do something. So they go to the mayor, they go to the police chief, and then there’s this effort to start to clean stuff up. As it gets cleaned up, the people who are there end up having to leave and they’re replaced by people who didn’t have to put up with all the bad politics that went around living in the community.

Marshall: You talk about how you currently do some work or do work with the Oregon Department of Public Safety Standards and Training - the Academy - in Salem. You also talk about how tiring that work can be. So, my question is, what work do you do with the academy and why do you still feel it’s important to make the commute to do the work?

Brown: That’s where every officer in the state goes to be trained prior to being certified. Every time there was an issue, training was always a remedial action. I figured, well, they must not be doing what they need to do down there. So if I go down there, I can find out what that is and maybe begin to have some impact.

The first thing I realized was that what they’re being taught there is basic stuff. The bulk of the training happens when they go to their agencies. I felt some of the things could be changed down there so that when they went to their agencies they had a slightly different perspective on what they were being taught.

Richard Brown

When I went down to the Academy, they were not teaching the history of policing. We were able to get that to happen. Before I went down, I was on the committee that looked at developing training for police and my only reason for being there was to try to ensure that the issue of race was talked about.

When I got down there, that wasn’t happening. There was two or four hours designated to bias. Four hours and 16 weeks doesn’t do anything to get folks ready to come out and deal with people on the street - Black or otherwise. The job is about people so you got to know about the people that you’re providing a service to.

Those are the kinds of discussions I was able to have down there. There were some folks that didn’t want to hear it. There are folks down there who still don’t want to hear it. But there are a lot of folks now that want to hear that want to know what can we do better, That’s because people out here raising Cain. And it always happens. It’s cyclical. If we look at the issues that Black communities have had with police, there will be a time when everybody’s up in arms and they will come together and they’ll have these discussions and the dust will clear and everybody will go back to doing what they did before until it happens again.

For me, I don’t want to see that happen anymore. I don’t want to see us have to address a problem that we thought we addressed before. And the only way you do that is: you sensitize people to what the job is. You change their ideas. You don’t hire some of these folks because you’re just low on people. You’re low on people because it’s not attractive. Nobody wants to be a part of an occupational force.

Marshall: You say often if I don’t, then who will? Why do you say that so frequently in the book?

Brown: Over the years, I’ve been involved with the police, I’ve tried to get other people involved and I tried to get young people involved. You’re young, you have the stamina, you’re bullheaded, you’re not gonna let anyone pull the wool over your eyes. We don’t need to wait until it happens to us. If we get involved in these things, we may be able to head off some of this stuff.

A lot of times I feel like what I do at the Academy in talking to folks there is: I interpret what people are yelling about out here.

Richard Brown

They work together, but people have to be willing to commit to doing this stuff. I volunteered to do it. There is no job for anybody doing what I do and that’s a problem. because I don’t expect anybody to volunteer to do what I do. I do it because I’m retired and I can walk away anytime I want. I’m retired and I don’t have to worry about getting fired for saying something that they may not like down there. I volunteer, so they don’t write a job description so that when I leave, they don’t give that job to somebody that they know that doesn’t have the commitment that I have to what I want to see change.

Nobody wants to be told that they’re a collaborator with the cops. That’s not what I do. I try to let people know what I do so that they may not feel that is such a bad thing to be doing.

As much as we talk about Martin Luther King - we had Martin Luther King that was talking in a calm voice, using the King’s English. We had the Black Panthers, Deacons for Justice, and the Nation of Islam. We had all these folks that were out on the street. They had a choice of who they’re going to deal with.

I think changes that have happened have happened when there are people in both camps, and they’re working together to get this work done. I don’t have to go out on the street and march because there are people that know I’ve been there, and feel like that may have been part of the dues that I had to pay to get where I am. I’m only there because of the community.

Listen to Richard Brown’s full interview with OPB’s Paul Marshall using the audio player above