When Brian Grant retired from the NBA, he sunk into a deep depression. The life that he had fought so hard for seemed to evaporate and his marriage started to crumble. Also, he noticed a strange twitch in his hand. Eventually Grant was diagnosed with Young Onset Parkinson’s disease. He tells the story of his life and struggles in his new memoir “Rebound: Soaring in the NBA, Battling Parkinson’s and Finding What Really Matters.”

The interview below has been edited for clarity.

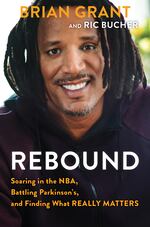

Grant's new memoir, from Triumph books, details his life and struggles with Parkinson's disease.

Courtesy of Triumph Books

You credit your uncle with helping you get better at basketball in a kind of sneaky way. What did your uncle do?

I didn’t realize it until I started writing this story, getting this book together, and I started talking to the cats that used to rock me up on the court. I’d go to these courts called the Ripley courts and there were a lot of other individuals that I’ve grown up around. They were four or five years older than me, and for the first three weeks, I couldn’t understand why they were beating me up.

Like, literally, I got home with bloody nose, busted lip, you know, bruises and cuts and scrapes from getting slammed on on the concrete court. And it wasn’t until I was working on the book and I spoke to them and, first thing they told me, to my disbelief, the one person I kept telling them I was gonna run home and tell was my uncle John and they go: “We weren’t worried about it because he’s the one that told us to do it.” He saw something in me. I don’t know how or why other than the fact that I was taller than everybody, he was like: “If he’s gonna go out there, we got tough him up. He’s too soft right now.” And that’s what they did. I think it was after that that I started going down and I started roughing them up, you know, started just dunking and the beast came out and that was it. It didn’t go back to sleep.

You were the eighth pick overall in the first round of the 1994 NBA draft. What do you what do you remember about that moment? A kid from rural Ohio who had only been playing basketball for a handful of years to make it to the NBA.

All the way up until after my last college game against Northwestern that we lost, I didn’t think I was going to the league. I thought basketball was over for me. I thought: I have a degree and I don’t have to live in my little small town anymore. I can branch out and be in Cincinnati and maybe save some money and move down to Florida, move out west to California but I had options available to me. Basketball just wasn’t one of them.

You write in the book that you played that entire first season with a torn labrum, a serious shoulder injury after trainers and doctors said you couldn’t play. What was that that first Portland season like for you physically?

Pain, just pure pain. When I arrived in Portland, you got to remember that this is when everybody was either traded away or left. The beloved Blazers, you know, gone. And I just knew that if I didn’t play, it really didn’t matter what kind of season I had the following year or any year from there, I’m always gonna be that person that got the good guys kicked out or moved on. I just didn’t think they would ever respect me. That that meant more to me than whether they liked me.

You are known for being super physical, a tenacious rebounder, relentless presence. Even though you were often matched up with people over the course of your career who were bigger than you. I mean, just for one example, what was it like to go head to head against Shaquille O’Neal for most of a game?

I mean, it was a challenge. I kind of like to live for the battle. The game was important, but the battle was even more important to me. If you ask Shaq, he’s gonna say: “He stepped to me like a man.” When he’s on, he’s unstoppable, but you just try your best and you just keep banging and hitting and getting hit, taking elbows to the head, you just keep on fighting.

Let’s turn to Parkinson’s. One of the first times when you really knew that something was wrong wasn’t in a game, it was in a practice when you went up for a dunk. Can you tell us about that moment?

I knew something was wrong even before that, I just knew that I wasn’t able to jump off my left leg. It felt uncoordinated and that was my strong leg. But I was playing pickup games with Kurt Thomas and I blew past him and went up and it just, I guess it looked pretty ugly and awkward and uncoordinated. And he was like: “What’s wrong with you?” And so after that I went and saw the neurologist and I had a little skin twitch in my wrist and he said: “You know what? You’ve been in the league 12 years. Your body is worn down. You’re gonna have little twinges and twitches. It’s nothing to worry about.” And so I didn’t think anything of it.

A Parkinson’s diagnosis can be devastating for anybody, but the way you describe this as a professional athlete, it seems like you were dealing with an extra level of of your body’s betrayal because your body had been able to do things that very few people on earth could do: moving with speed and strength and agility night after night, at just at the highest level. What was that particular loss like for you?

I was injured a lot. And you’re used to being able to get a prescription, get a surgery or you get some type of rehab to correct it and you’ve been doing that for years and all of sudden there was this thing that starts up and you’re told there’s no cure and you’re slowly going to start to lose different abilities and different faculties of your of your body. ... At first you’re just like: “But I don’t feel that bad other than this twitch!” And then you go through depression. The deep dark depression lasted nine months. It’s a hard pill for anybody to swallow, not just Brian Grant or any athlete, but I think the thing that makes it tougher for me is because I’ve seen so many things corrected and fixed with surgeries and medications that it’s hard to believe that this one can’t be fixed.

The way you dealt with with both getting to the highest level of professional basketball, but also coming back from injuries was by hustling. By working as hard as you could and harder than a lot of people around you. But in this case you can’t work out your way out out of Parkinson’s. What has helped you over the last 10 years? What’s given you solace?

The friends that I’ve made who share this disease with me, they give me solace. They give me hope that I’m not alone and here is someone who really understands what I’m going through.

Contact “Think Out Loud®”

If you’d like to comment on any of the topics in this show, or suggest a topic of your own, please get in touch with us on Facebook or Twitter, send an email to thinkoutloud@opb.org, or you can leave a voicemail for us at 503-293-1983. The call-in phone number during the noon hour is 888-665-5865.