In January, the Office of Community & Civic Life — a Portland city bureau long lamented as a catch-all for city services — landed in the lap of an unexpecting Commissioner Jo Ann Hardesty.

Looking to meet her new staff, Hardesty called her first all-staff meeting two weeks ago. All bureau members were invited except one: Director Suk Rhee.

Hardesty, who took on oversight of the office after the mayor reshuffled bureau assignments, said she wanted to create a “safe space” for staff members. Still, no one spoke.

Someone wrote in the chatbox, suggesting staff would be more forthcoming if Hardesty asked managers to leave. She did.

Soon, a torrent of allegations came flooding out: harassment by higher-ups, inexperienced managers, inappropriate hiring practices, and a culture of retaliation.

Portland City Commissioner Jo Ann Hardesty listens to testimony over a proposed ordinance on April 4, 2019.

Kaylee Domzalski / OPB

“The general theme was intimidation,” recalled Hardesty. “I had people say they had been in staff meetings where most of the people left crying in tears. I heard people are bullied. They are just not treated like the professional adults that they should be treated like.”

For years, rank-and-file staff has been sounding alarms about management at the bureau that they allege ranged from sloppy to abusive: filing at least 4 complaints with human resources, 11 union grievances and an estimated 20 complaints with the city’s ombudsman. The bureau’s turnover rate alone, in the words of one labor expert, should have cast a “flashing red light” over management problems: records show an exodus from the bureau since 2018 with at least 31 regular staff members departing from the bureau, one of the smallest in the city. That includes staffers who were fired, retired, quit or transferred out. More than half of those who left were people of color.

In late 2019, citing complaints that “defy categorization,” City Ombudsman Margie Sollinger wrote a memo to city officials, recommending they hire an outside workplace consultant. The findings of that review are expected in mid-March.

But there’s been uncertainty voiced by both the ombudsman and staff over whether the review, carried out by strategic design consultancy firm ASCETA, will be enough to hold higher-ups accountable for the alleged hostility. One staffer worried it would be like “putting a Band-Aid on an open heart surgery.”

OPB interviewed 13 current and former staff members who said the city failed them during their time at the bureau. Now, as the office changes hands, staff hope city officials are ready to reckon with the dysfunction and deep-seated unhappiness that has beset much of the frontline staff for years.

Hardesty hasn’t yet decided what steps she’s going to take to course-correct. She’s said she’s still in the “due diligence” phase.

But, after looking under the hood of her new bureau for a month, she’s seen enough to apologize for what she calls the most hostile workplace she’s ever witnessed.

“I apologized,” she said, “because no one should have to work under a culture of fear.”

The problems

Civic Life staff have been known to refer to their office as the island of misfit toys: a host of distinctly different programs bundled under the same bureau. The workforce has fluctuated in size over the last few years, ranging from a high of about 60 to a recent low of about 45.

Portlanders turn to the office to deal with their noise complaints, regulate their cannabis shops and liquor stores, and scrub off unwanted graffiti. Most notably, the bureau oversees funding for the city’s network of 95 neighborhood associations, local groups responsible for promoting civic engagement.

The disjointed programming has fueled problems for years. When Portland Mayor Ted Wheeler was elected into office in 2016, he tied civic life for first place with the police bureau as the department most in need of reform. An audit around that time described the bureau, then called the Office of Neighborhood Involvement, as a rudderless department in need of fresh leadership.

The new leadership arrived soon after. Commissioner Chloe Eudaly, who left City Hall last December after losing her re-election bid, had inherited the troubled bureau in the wake of the 2016 audit. She promised to deliver a major restructuring to make the bureau more inclusive to renters and people of color. After the longtime director resigned, she appointed Suk Rhee, a vice president at Portland-based charity Northwest Health Foundation, to carry out her vision.

Portland City Commissioner Chloe Eudaly listens to testimony at City Hall in Portland, Ore., on April 4, 2019.

Kaylee Domzalski / OPB

Some staff alleges that change in direction came hand-in-hand with new forms of harassment from higher-ups.

Rank-and-file staff said they watched as people who disagreed with the bureau leadership got pushed out through harsher than expected performance reviews and changing job requirements. They said they were told not to speak to anyone except their direct supervisor during the workday. Multiple people said they made a conscious decision to stop speaking during meetings.

“From my corner of the world, things were becoming very restrictive, very hostile. We didn’t feel safe,” said Linda Castillo, a former bureau specialist who helped immigrant and refugee communities engage with city projects. “...We’re feeling like, ‘What the heck is going on?’ We don’t know where we’re going, we don’t know who’s running the ship. Nobody’s talking to us.”

In 2019, Castillo said she brought up the changing culture with her supervisor, remarking that she felt debilitated by how directionless the bureau felt. She said her supervisor told her to “get the fuck over that.” She later emailed a lengthy complaint to the city’s human resources bureau. She got a response two months later, critiquing her job performance and saying her allegation of harassment had been found unsubstantiated.

Castillo said she left City Hall last year to protect her mental health. She said her exit interview with Rhee was the first time she ever heard someone within the bureau bring up her complaint. According to Castillo, Rhee asked if she really expected the office to take it seriously.

In an interview, Rhee denied the claim, as well as the larger allegations brought by both staff members and Hardesty that there was a systemic problem with abusive management within the bureau.

“We have growing pain. We have transition. We have actual reform and transformation going on,” she said. “Do I feel that there’s any abuse going on by supervisors in this process? Absolutely not.”

The change

Over the last three years, Rhee has heeded Eudaly’s call to act as a change agent.

Under her watch, the bureau’s name changed to the Office of Community & Civic Life, a rebranding they said was intended to underscore the office’s desire to reach all Portlanders. The bureau transitioned away from supporting neighborhood watch groups and offering a crime prevention program, which leadership said was a fear-based, dated model. Most memorably, the bureau made a doomed attempt to change the city code and reduce the influence of the city’s network of neighborhood associations, where leadership leans white and wealthy.

Internally, Rhee began hiring more people of color in management positions. Demographic data shows the bureau has become increasingly racially diverse under Rhee’s watch with the number of people of color within the bureau roughly doubling since 2017. Rhee said all supervisors are people of color.

“We are becoming a bureau that’s multicultural — and multicultural in a city that is still at the very beginning of its anti-racist practices is going to be challenging and hard to understand for some,” she said.

“In the context of these allegations, they really do deserve to be understood against this backdrop.”

But some have pushed back on the assertion that the bureau’s high volume of complaints can be explained away by the employee’s tenure or by their race. The city ombudsman wrote in her 2019 memo to city officials that the deluge of complaints went far beyond the “expected growing pains associated with change.” They were brought by longtime employees and newer hires, white people and people of color. At least 18 staffers of color have departed since 2018.

While the memo was written over a year ago, the allegations of problematic management have persisted. A staff member in the bureau’s community safety program said their supervisor recently ordered staff to start counting the number of attendees at community meetings who appeared to be people of color. The manager was concerned white people were dominating the meetings. The staff member, who is a person of color, said they felt uncomfortable with the tactic, which found them eyeballing people’s race over video calls.

Nicholas Carroll, a support specialist for the bureau’s noise office who is biracial, said the director typically gave managers wide latitude to manage staff how they saw fit. He met with Rhee once to discuss a workload-related grievance he had filed against his manager.

“She told me three times in our 30-minute conversation that ‘managers have a right to their personal management style and personality,’” Carroll said. “Basically she was saying that they were abusive, get over it.”

Carroll said his supervisor, Kenya Williams, was often unprofessional, publicly disparaging the job performance of his subordinates and discussing them in crude terms. He said Williams asked him to think ‘fuck you’ when on calls with the public.

While under investigation by human resources, Williams took a new job at the Parks bureau as the equity & inclusion manager. He did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

Rob Martineau, the president of the local AFSCME union chapter for city employees, currently represents about 20 employees in the civic life bureau. In the last few years, he has seen at least 11 grievances filed out of the group — a figure he called “by far, the most in the city.” All complaints have been related to issues with management.

“There hasn’t been a willingness to recognize that the rank and file that are doing the feet on the groundwork have a say and have an opinion,” Martineau said. “It felt very much like a top-down structure where it’s my way or the highway.”

The systems that failed employees

In May 2019, the bureau’s leadership team went on a one-day retreat at the Kenton Firehouse, a historic firehouse turned event venue in North Portland. A mediator handed out markers and paper and asked the team to draw where they felt the bureau was headed.

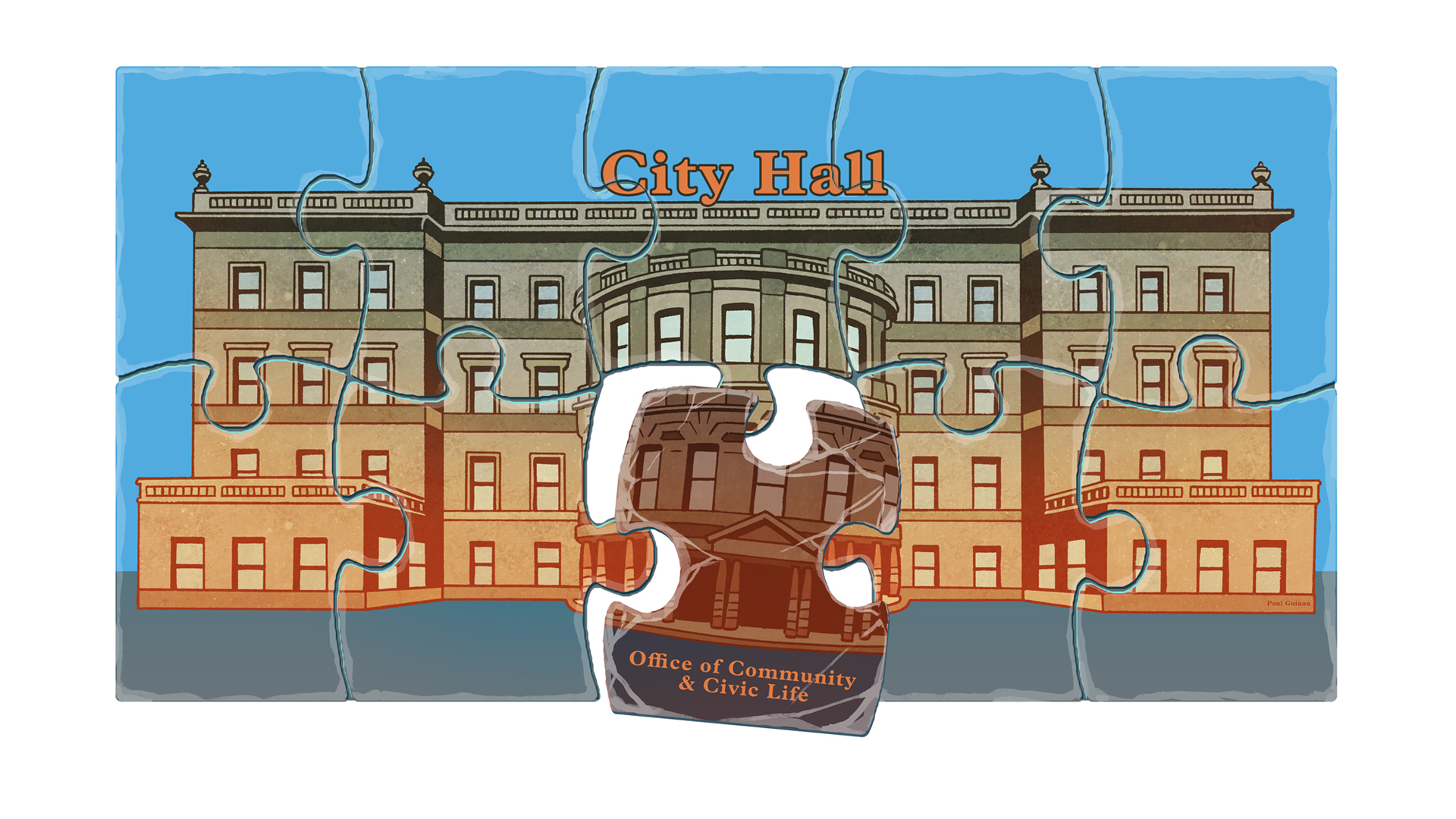

All the images gave off a sense of discord and chaos, according to three people in attendance that day. One person drew stick figures repeatedly climbing and slipping off mountain ranges. Someone else drew the director trying to put together pieces of a puzzle in disarray. Another recalled seeing a drawing of scribbles on top of scribbles that resembled a whirlpool or maybe a black hole.

The retreat sticks out in the minds of some of these employees as the first major should-have-been reckoning moments for top leadership: an entire team staring at a wall of disconcerting doodles.

Two years later, these staff members say the inflection point has yet to arrive.

To understand how a toxic work environment was able to fester for so long, staff say you have to look beyond the bureau to more foundational flaws within City Hall. They point to two structural problems: an ineffective human resources department and a commission form of government.

Some members speculated in a more typical form of government — where an entire city government shares responsibility for a bureau-in-distress — another council member might have intervened. But under Portland’s unique form of government, these members allege they were siloed under a commissioner who was slow to see the wave of grievances building.

Hardesty said civic life staff told her they never met Eudaly face-to-face as a group during her time overseeing the bureau. Multiple staff members told OPB they reached out to members of Eudaly’s staff to discuss issues with the work environment, but nothing ever came of it.

“The concerns were certainly heard,” said Martineau, the AFSCME president, who also had conversations with her chief of staff. “But being heard, and seeing changes — that’s where the disconnect was. We just really haven’t seen the changes.”

In an email to OPB, Eudaly adamantly rejected the assertion that her office was unresponsive, saying her staff spent copious amounts of time working with bureau employees who were failing to perform basic duties.

She also said she believed that the flood of complaints over to the ombudsman’s office was politically motivated, taking place in the midst of her re-election campaign. Her opponent Mingus Mapps, who ultimately took her seat on the council, had been fired from the civic life bureau and regularly discussed the bureau’s issues on the campaign trail.

“The group complaint to the ombudsman was very obviously politically timed to pressure me into taking action to satisfy some of the complainants or risk having it negatively impact my re-election campaign,” wrote Eudaly. “I chose the latter.”

Eudaly said she had made it a personal rule to not meet with disgruntled employees but trusted her leadership team, as well as human resources to deal with personnel issues.

Some staff says that’s where the most glaring structural problem is.

Jeri Jimenez, a former diversity and civic leadership coordinator, said she filed a complaint with human resources in 2018 about a manager she alleged was abusive. Jimenez said her manager repeatedly yelled at her with expletives and ordered her not to talk with her colleagues. She said she went on medical leave, after going into work began triggering her PTSD.

Jimenez said her statement got routed back to the bureau director to decide whether to act on, a move she felt put a target on her back and doomed the complaint.

“HR said, ‘Oh, we’re not the ones making the decision. The director’s going to make the decision,’ Jimenez said. “Well, the director hired the person to do this. Do you really think that the director’s going to say anything was wrong?”

Human resources reported four complaints that have been filed by bureau staff since 2018. Two remain open, and two were not investigated because the allegations didn’t violate city rules, according to Heather Hafer, a city spokesperson.

Many interviewed by OPB expressed distrust of the human resources process, which they said often ended up with their grievances lingering too long with their human resources representative or hitting a dead end on the director’s desk. One current employee, who called OPB from a blocked number, said she was too scared to put her name on a complaint.

The bureau’s human resources representative recently stopped representing the bureau. Hafer said the human resources director decided “it was in the best interest of both the bureau and the bureau’s Human Resources representative.”

Hardesty said she expects to look into how human resources handled civic life complaints, in addition to the outside review the city ombudsman requested. Hardesty said she plans for that document to be the final piece before deciding how to change the bureau’s course —though she’s settled on one new policy.

“We have to be sure that there’s a clear set of expectations that employees will not be bullied, intimidated or treated disrespectfully in any way,” she said. “That’s the culture that will be the new culture of civic life moving forward.”