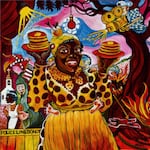

Arvie Smith's "Hands Up, Don't Shoot" illustrates the way the longtime Portland artists uses racial tropes, humor, and discomfort to challenge the way his audience sees the world.

Courtesy of the Portland Art Museum

Portland artist and Pacific Northwest College of Art professor emeritus Arvie Smith has a show opening at Portland Art Museum's APEX Gallery that goes on view on Saturday, July 30.

With all of the recent police shootings of African American men, his vivid, explosive paintings provide a sense of cultural commentary that might make you think they were created last week. Smith recently talked with us about his paintings, being an African American man in Portland and how none of the recent shootings are anything new.

Q&A with Arvie Smith

April Baer: Perhaps the most striking image in the show is one titled “Hands Up, Don’t Shoot.” It’s an intensely colorful portrait of a beaming Aunt Jemima, two plates of pancakes raised high above her head and a movie camera focused on her. How did that image come to you?

Arvie Smith: That was a reaction, partially, to the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. He was gunned down by policeman as he was fleeing. He was left on the street for four hours. That harked back to something my mother told me, she said, 'This used to happen all the time.' They would just kill the people and throw them at your doorstep.

Baer: How have you been affected by watching videos like the death of Alton Sterling?

Smith: It's nothing new. In fairness, I don't think every white person you meet understands or believes that that really happens to black people on a daily basis, and they don't believe that somehow because of those actions they are presented with privilege.

Baer: Are you saying that you have seen things like this happen before and so in that sense it’s not new? Or just that this was so much a part of the truth of African-American life that seeing it on video was not as much of a shock?

Smith: It's happened to me. And I know the rules. I know when the police stop me I better have my hands on the wheel. I know that when I'm stopped by a police officer my life is in danger. I'm totally aware of that. I think every black male is aware of that.

Baer: How often does that still happen to you?

Smith: It happened last year. I complained in a restaurant to the manager that the food that was served was not cooked properly and he told me to get 'Your black ass out of here and don't come back.' And I said 'No, I'm not leaving.' He wanted me to pay for this food and I said, 'No, I won't do that,' and he said, 'I'll call the police,' so I said, 'Sure, call the police.' I thought I would have a chance to confront him and we would talk it out. The police saw me, they ran, grabbed me, rustled me, handcuffed me and held me for about an hour. And all I was trying to do was to have some kind of fairness, some kind of equity, which is sadly missing.

Baer: Do you mind saying how old you are?

Smith: They perceived me as black. I did a project with kids in JDH — a juvenile home. I did a two-year project working on some murals that are now in the courthouse justice department. And what I saw were black children — people of color — of being prosecuted, of being charged with felonies and encouraged to plead down to another felony, but they're going to be ruined for the rest of their lives, but that was the advice that their lawyers were giving them to plead to these things. And what I see happening on Martin Luther King (Boulevard) and other places is that these policeman are just picking the low hanging fruit — the people who can't afford to fight back.

Baer: You have another painting that is a reference to Edvard Munch’s "The Scream," featuring an African-American figure screaming with hair standing on end. The title is “We Be Lovin’ It.” I take it that’s a reference to a McDonalds commercial that was made a few years ago. What brought on the idea of adapting Munch?

Smith: I was driving down Burnside, and I saw this billboard on the McDonald's restaurant, and it just looked so much like the image of Buckwheat.

Baer: Can you describe the image for us?

Smith: The image was a black man, afro, and he's got two white women on the side. One might have been black. These comical images of black people have been around since after the Civil War. We got Buckwheat in the '30s and '40s and to me that obvious reference to Buckwheat talks about the merit of the person they're depicting. I was so infuriated that I had to do something about it. I had to paint about. And with the killing of this young man it just all tied together. You can kill a Buckwheat. You can kill something that you have dehumanized — something that is no longer human to you — it's a lot easier to dispose of.

Baer: What brought on the idea of adapting Munch?

Smith: "The Scream" — I feel that all the time. And I'm sure many black people feel like, you've been put in a compromising position, and what are you going to do about it? You're not going to scream there, but you might go home and let it all hang out.

Baer: Curator Bonnie Laing Malcolmson writes in her curatorial statement, “Arvie Smith’s paintings attract and repel us at the same time; they make us want to laugh and want to cry. We are, at the least, embarrassed; at best, profoundly ashamed. For what is the appropriate response to unmitigated, casual oppression? What is the appropriate response to murder?” How do you think about that?

Smith: The appropriate response is that these people be held accountable. I think the appropriate response is that we agitate, agitate, agitate.

Baer:What do you hope your painting has been able to do?

Smith: I hope very much that it stimulates some dialogue. It's difficult to talk about race relations. Nobody likes to talk about it. I don't like to talk about it. White people don't like to talk about it. It's uncomfortable. I have to bite the bullet and say, 'OK, I'll be uncomfortable, and I'm trying to make you uncomfortable, too, so that we can talk about why it is that we are so uncomfortable.' We can talk about sex but we can't talk about race.

Smith's work will be on view at Portland Art Museum's APEX Gallery July 30–November 13. For more about Smith, check out this Oregon Art Beat profile of the artist.