The Chuck Close Exhibit at Pendleton Center for the Arts runs through April 29

courtesy of Pendleton Center for the Arts

Big cities aren’t the only places to see works by major artists. Sometimes you have to head to a small town.

On a Tuesday morning, three classes of sixth-graders crowd into the Pendleton Center for the Arts to face down a selection of Chuck Close’s portraits, on view through April 29.

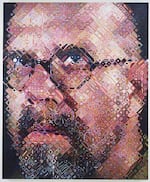

“Come on in, crowd around,” said Bonnie Day, the center’s coordinator of education and outreach, as she invited the students to cross the room towards an 111-color, screen-printed self-portrait, complete with the preeminent artist's trademark glasses and goatee.

“Especially you guys who are the very closest: What did you notice as you got closer?”

“It just looks like a random mess,” said 12-year-old Caleb Picken.

Like much of Close’s work in the past few decades, this portrait is made up of a grid of squares, each filled with concentric squiggly circles of contrasting colors. So while it has an incredible likeness of Close from across the room, it devolves into what looks like a bunch of Easter eggs flattened into a grid up close.

Spread throughout the gallery are 13 such portraits: Philip Glass, Brad Pitt, the artist Lucas Samaras, Close’s niece and several of Close himself. All are prints.

Chuck Close (American (b. 1940)) Self-Portrait, edition 18/80, 2000 111-color silk screen

Courtesy of the Jordan Schnitzer Family Foundation

“We chose a wide range of printmaking processes,” said Executive Director Roberta Lavadour, “so people would be able to kind of get acquainted with the difference between, you know, how does a Ukiyo-e Japanese woodblock sit on the paper versus an 111-color silkscreen with oil-based ink? How does that sit on the page? And the same thing with the etchings and the woodburytypes and the spitbite pieces.”

It’s not every day that a small-town art center gets to select works from a blue-chip artist like it’s checking out library books, but that’s basically how this show came to be. Lavadour saw information on a number of touring exhibitions drawn from the collection of the Portland arts patron Jordan Schnitzer. On a whim, she emailed him to see if she might borrow a couple of works, too.

“And the phone rang within three minutes, and it was Jordan on the line saying, ‘I love this. Let’s do it,’” she said.

Lavadour traveled to Schnitzer’s Portland office to go through binders documenting his 11,000 prints. Then his family foundation covered the costs to ship and install the art and to send instructors into local sixth-grade classrooms to do an art project inspired by Close's process.

Out of all the artists in Schnitzer’s collection, Lavadour chose to feature the works of Close because they are so recognizable, and yet there’s still a lot of things people don’t know about the artist.

“His personal story is really fantastic,” she said. “To be able to talk to kids in the gallery about the fact that he overcame so many obstacles, some of the things that they face — you know, learning disabilities and physical limitations — and how he worked with that to really find what he was good at.”

Close struggles with dyslexia and a disorder called prosopagnosia, or face blindness, which means he has incredible difficulty recognizing and remembering faces. He has said he focuses on portraits in part because there’s something about flattening the faces of friends and family into two-dimensions that helps him to remember them.

Then later in life, he suffered a spinal artery collapse that left him a quadriplegic. Lacking fine finger dexterity, he now straps a brush into his hand, which is part of the reason he abandoned the photo realism that made him famous for the looser style that appears abstract up close.

The art center has partnered with the schools to teach students his process.

“We did a unit a couple weeks back where we made a big grid, and we would color each square in,” said 12-year-old Molly Reeves. “We basically did the exact same that Chuck Close is doing.”

“Except we did cartoon characters,” Picken chimed in. “It was kind of weird: If you did just one square and then another, it was like putting a puzzle together.”

“At first it didn’t make much sense,” Reeves continued, “but then once you put it all together, you were just sort of blown away by how it made this picture, and it was really cool.”

Schnitzer said it’s moments like these that fuel him to send his works into smaller communities.

“I cannot tell you — there’s no room left in my heart — the joy it brings me to get this work out to these audiences,” he said.

His foundation has at least a dozen shows touring this year, including the recent Andy Warhol exhibition that showed at the Portland Art Museum and exhibitions by Kara Walker and Richard Serra.

Lavadour said she hopes "Chuck Close: Selections from the Collections of Jordan D. Schnitzer and His Family Foundation" is just the first in a series of annual blockbuster shows the Pendleton Center for the Arts can host from his collection.

Related: 100 Years Of Cowboys And Indians Pageantry In Pendleton

Schnitzer is no stranger to Pendleton. He’s been going to the Pendleton Round-Up for 35 years and has helped fund projects in town, including the art center and his most recent purchase, an old bank building.

“They shut down main street for the Round-Up, and there are two or three country western bands and all the little pop-up restaurants and shops,” he said. “And there was a building on the corner that was always closed, and it just looked terrible to me.”

So when it went up for auction last May, he bought it. Then he invited Crow’s Shadow Institute of the Arts to do a pop-up store to sell their prints in it during last year’s Round-Up.

“Now we’re working with OMSI, seeing if OMSI might want to develop a satellite in Pendleton,” he said. “They also talk about wanting a smaller grocery store downtown. If it’s a business and commercial thing, that’s fine. If it’s a nonprofit thing, there’s no rent, and they can just use it. I just want to see that community continue to become all that it can be.”

Schnitzer is also funding $5 million of the $11 million price tag for the new Museum of Art at Washington State University in Pullman that will bear his name. It's set to be completed in spring 2018. And he said he has more big news coming.

Of course, the Pendleton Center for the Arts and the bank building aren't the only arts stories brewing in downtown Pendleton. The Rivoli Restoration Coalition just got its architectural plans approved to transform the derelict historic theater into a cutting-edge performing arts center. They're breaking the project into three phases — general structural work, the meat and bones of the performing arts center, and finally the details.

Their plan is to take their time and raise the money as they go so that they won’t have to carry any debt when the project is finished, as that’s the kind of thing that can tank a nonprofit. Coalition member Andrew Pickens (who also happens to be Caleb Pickens father, because, you know, small towns) said he’s optimistic they can raise enough of the $560,000 first phase to begin construction in June.

“Pendleton is the kind of place,” Pickens said, “where if you love it, it will love you back.”