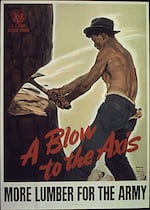

Two-man chainsaws only enjoyed a brief window of popularity before lighter, easier-to-use one-man models came along.

Courtesy of the U.S. Forest Service

Growing up, Paul Skirvin milked a lot of cows.

"Dad went and borrowed the money," he says. "And before we was through milking cows, we was milking about 60 head."

This was outside of Portland in the 1930s and '40s. Skirvin was too young to fight in World War II. Soon after it ended he received a quick lesson in economics when he and his brother were hired to log off their neighbor's land.

“We milked those cows all month and [made] about the same as we’d make in a week logging.” he says.

WATCH: Battle Ready - The Digital Documentary

That was the end of the dairy but the beginning of a 50-year career in the woods.

There couldn’t have been a better time for the Skirvins to get started in the industry. World War II had set the country on a new prosperous course – not only economically but technologically as well.

Tree cutting became far quicker and easier because the war helped push the most iconic symbol of modern logging — the chainsaw — into the hands of the Northwest logger.

It changed the industry forever.

Two-Man Monstrosities

Chainsaws were around before the war, but they were two-man monstrosities.

“If you are talking the chainsaws prior to the war, you would be some place where they had typically an electric machine,” Wayne Sutton says. “They had big generators mounted on crawlers or tractors of some sort … and the chords were the size of a garden hose.”

Sutton would know. His museum in Amboy, Washington, has one of the most extensive collections of antique chainsaws in the world.

The pre-WWII chainsaw wasn’t exactly a grab-and-go piece of machinery. It took two men to use one. One man would grab the engine, and the other would take a hold of a handle attached to the chain end.

The early versions were designed to saw vertically for bucking — cutting the fallen tree to the proper length for the mill. Tipping the saws would disrupt the fuel flow and kill the engine.

Wayne Sutton displays hundreds of saws in his Chainsaw Museum in Amboy, Washington. It’s one of the largest collections of antique chainsaws in the world.

Jes Burns, OPB / EarthFix

Loggers were wary about taking them on, University of Oregon historian Steven Beda says. One reason was fear the chainsaws would reduce the number of men needed to work in the woods. There were more practical unpleasantries as well.

“The early chainsaws were loud, they were nasty, they spit oil, they spit gas,” Beda says.

But World War II’s demand for raw materials changed the dynamic.

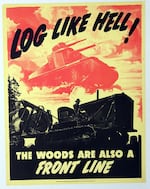

‘The Woods Are Also A Front Line’

The United States needed an enormous amount of natural resources to fight World War II. Crude oil for fuel, rubber for tires, and iron ore and other metals for everything from submarines and torpedoes to airplanes and aerial bombs. In the Pacific Northwest, the raw material of greatest value to the war grew tall and green.

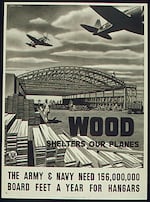

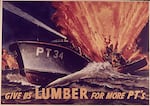

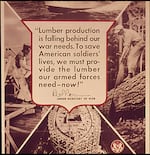

The U.S. wartime need for timber was great, and labor shortages forced the government to exempt loggers from the draft.

National Archive

Wood was needed to build hangars, barracks, ships, trucks, planes, bridges and crates for shipping supplies and ammunition to Europe and the Pacific.

It was a jolt to a timber industry hit hard by the Great Depression.

“Then there is a big resurgence in World War II — such a demand for timber,” Beda says.

A propaganda poster of the time captured the get-out-the-cut urgency: “Lumber production is falling behind our war needs. To save American soldiers’ lives, we must provide the lumber our armed forces need – now!”

Related: How Nazi POWs Almost Became Loggers In Oregon And Washington

A once-idled timber industry workforce suddenly had more work than it could handle. When the war started, chainsaws still weren’t common in the forests of Washington and Oregon. But in their desperation to meet the wartime need, more and more crews turned to the technology to speed up the cut.

The rhythmic thump of the ax and the sweet song of the hand saw gradually faded as Northwest forests filled with the harsh buzz of the two-man chainsaw.

That helped Northwest loggers cut so much lumber for the war effort that — had it not been required for barracks, crates, and the like — it could have framed 3.5 million modern houses.

Cheaper, Lighter, More Powerful

But the two-man saw wasn’t long for the woods.

Manufacturing had improved rapidly during the war. Within a few years of V-J Day, the one-man chainsaws started to show up.

“The fact that a chainsaw now becomes a lot cheaper and a lot more easy to manufacture has to do with this new industrial infrastructure created as a consequence of the war,” Beda says.

Paul Skirvin remembers when the one-man chainsaw appeared at retailers in the Northwest.

Retired Oregon logging company founder Paul Skirvin's career spanned the post-war expansion of the late 1940s to the Timber Wars of the early 1990s.

Kerin Sharma, OPB / EarthFix

“We got our first power saw then, from Monkey Ward, I think it was,” he remembers, referring to the department store Montgomery Ward.

The 60-pound one-man chainsaw meant Skirvin and his brother could work much faster.

“After you got a power saw, man, [you] just zip it a lot faster. Ten, five, eight times faster,” Skirvin says.

The historic wartime demand for timber was quickly eclipsed by what came next: the post-war construction boom.

Suburban developments sprang up around the country. Businesses followed the migration to lower-cost outskirts as well.

The Northwest and its comparatively untapped timber resources answered the call.

“They kept building more houses. You had to keep producing more because they was building more houses,” Skirvin says.

The mills in Oregon and Washington would take all the timber the Skirvins and other logging outfits — and their chainsaws — could get them.

“If you live in a house made in the 1950s, 1960s, I can almost guarantee that it is Washington and Oregon lumber that built that house,” Beda says.

Legacy Of The Chainsaw

Northwest forests have paid an ecological price for the heavy harvest of the post-war era. Fish and wildlife habitat was decimated. By the mid-1990s, as much as 90 percent of old growth forests were gone.

Source: Oregon Department of Forestry, Washington Department of Natural Resources

During World War II, the timber industry in Oregon really took off. Before the war, most of the cut was coming from Washington, but as demand increased, the relatively untapped woods of Oregon became the primary source for Northwest timber. Credit: Tony Schick, OPB/EarthFix

Now the cut is lower and much more regulated — especially on public lands. There’s a high premium put on treading lightly, selective logging and avoiding soil compaction.

As a result, an industry that transformed itself after World War II with the chainsaw is once again looking to technology to adapt to these new environmental expectations.

Because of this, there’s still room for newcomers to make their mark. Matt Hegerberg of Hood River, Oregon, is part of the newest generation of logger.

“Essentially what we do are the more sensitive and more difficult jobs, [rather] than a lot of clear cuts and easy jobs,” Hegerberg says.

Hegerberg’s family has been connected to the timber industry for four generations. But when Hegerberg first decided to get into the business, his family had reservations.

“My mom hated it. Hated it! She was worried about me getting hurt or that persona that loggers are — whatever persona you want to believe about loggers,” he says “So she didn’t want part of me being out here and wasting my college education.”

But Hegerberg’s company, WyEast Timber Services, has been a successful small business.

“I think she is OK with it,” he says of his mother’s current feelings about his choice of career.

In the new era of forestry, companies like Hegerberg’s take on jobs like thinning, restoration and fire treatment. Innovative equipment is the key to making this kind of work profitable.

“We aren’t dealing with great, big trees with no limbs on them. It takes a lot of work to get the volume that we would get if we [were] doing clearcuts, or old-growth cuts,” he says.

With equipment like the feller buncher and the dangle-head processor, one logger can cut a tree down in just a few seconds. Then it only takes a few more to shear off the limbs and cut it to length. The relatively small and light back-hoe type vehicles can maneuver in dense forests, target specific trees and control their fall.

But this equipment doesn’t solve all of Hegerberg’s problems on the job site. And he still turns to a tree faller with a chainsaw when the ground is too steep, the brush is too thick or the ecosystem too fragile for large machines.

“It plays a very important role in what we do. We keep one in every single one of our pickups. We use them almost daily,” he says.

And even today, when logging is more hands-off than ever before, no self-respecting logger would go to a jobsite without a chainsaw in tow.

WWII lumber poster

Courtesy of the National Archives