An emaciated sea lion pup in California's Channel Islands.

NOAA Fisheries/Alaska Fisheries Science Center

It’s a double-whammy kind of year for the Pacific.

An unusually warm winter in Alaska failed to chill ocean waters. Then this winter’s El Nino is keeping tropical ocean temperatures high. Combine these and scientists are recording ocean temperatures up to 7 degrees Fahrenheit warmer than average off the coasts of Oregon and Washington.

“This is a situation with how the climate is going, or the weather is going, that we just haven’t really seen before and don’t know where it’s headed,” says National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration fisheries biologist Chris Harvey.

Harvey is a lead scientist on the California Current Integrated Ecosystem Assessment, which was recently presented to Northwest fisheries managers.

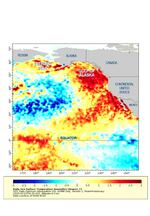

This map shows sea surface temperatures off the West Coast. The darker the red, the farther the temperatures are above average.

NOAA Fisheries

Pacific Ocean temperatures regularly swing along a temperature spectrum. In fact, scientists have identified multi-decade cycles of warmer and cooler water.

“But right now, in the last couple of decades, we feel like we’ve seen maybe a little bit less stability in those regimes,” Harvey says.

This year, the temperatures are particularly high. The effects already appear to be rippling up and down the food chain.

When the ocean is warmer, it is less nutrient rich.

The humble copepod is a good illustration of this phenomenon. Copepods are small, crab-like organisms that swim in the upper part of the water column. They’re basically fish food for young salmon, sardines and other species.

But NOAA scientists have described the difference between cold-water copepods and warm-water copepods as the difference between a bacon-double cheeseburger with all the fixin's and a celery stick.

Cold-water copepods are fattier and more nutrient-rich, making them a higher-value food for fish.

This warm-water copepod collected off Oregon this winter. They provided provide less energy to salmon and other fish than cool-water species.

NOAA Fisheries/Northwest Fisheries Science Center

“The copepods that we associate with warmer water, which is what we’re seeing develop off the West Coast right now, tend to have lower energy content,” Harvey says. “There’s going to be probably an abundance of copepods out there, just not the high-energy ones we associate with higher fish production.”

Scientists are already making connections between these lower-nutrient waters and seabird die-offs in the Northwest and the widespread starvation of California sea lion pups, as well.

The warm water isn’t all bad news for Northwest fisheries. Some fish that like warm water, like albacore tuna, may be more abundant this year in waters off the Oregon and Washington coasts.

Harvey says the science suggests fisheries managers might want to take a more cautious approach when setting harvest rates in the coming years. But what these record-high temperatures say about the longer-term health of Northwest fisheries and other coastal wildlife is still unclear.

“For me the jury is out on this,” Harvey says. “We’re going to have to wait a couple years before we know if this was just a really, really bizarre bump in the road or if there’s more to it.”