Embrace Oregon encourages people to become foster parents.

A couple of weeks ago, the group's Facebook page contained the following post: “10 year old boy… spent the night in the office with two staff last night. For the past two days he’s been sitting in a DHS office waiting to find out where he’ll go next.”

Oregon Department of Health and Human Services

Embrace Oregon director Brooke Gray, a foster parent herself, said such stories are increasingly common.

“You know, as a community we want to speak dignity and worth and value over our children," she said. "Frankly, this isn’t sending a message of love and value.”

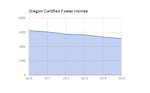

Over the last two years, Oregon’s foster care system has lost the equivalent of 400 beds in family homes and 100 beds in residential facilities.

Reginald Richardson of the Oregon Department of Human Services calls it a crisis.

"As a last resort, we have been forced to place children in hotels with supervision of at lest two DHS staff people," he said.

The problem isn't just what to do with children at night. During the day, the agency tries to get kids to school. But when that's not possible, Richardson says, they sometimes hang out in state offices.

"Our workers are very creative and entertaining in keeping those young folks occupied," he said.

Still, Richardson says, having children in state offices or hotel rooms isn't appropriate. And it's expensive.

A quick DHS survey one day last week found nine children in that position.

Richardson said children may stay in a hotel room for a night or two, but he hasn't heard of it happening for more than five nights in a row.

He said it also doesn't happen as much to kids who have been removed from their biological parents. In those cases, relatives can usually be found to care for the children. The more likely scenario for a child caught without a foster home to go to involves one who has, in Richardson's words, "blown out" of their placement — meaning their behavior has been so challenging that foster parents can no longer deal with them.

Still, why are so many foster families leaving the system?

"Foster parents have told me that they don't feel taken care of," Richardson said.

"They don't feel like they're part of our team. They have concerns about to what degree do we listen to them in terms of information about the children that are in their homes."

Richardson said the agency's focus on safety has increased the number of regulations that foster families have to follow. And some families have simply given up rather than meet all those new requirements.

He said the DHS is trying to reverse the trend by making staff available after hours — so families can get help during a crisis.

He said the agency is also talking to legislators about increasing the stipend foster families are paid and providing other financial assistance to help foster parents pay for child care. The state stipend starts at about $575 a month.

But money is not the reason most families get into foster care says Brooke Gray of Embrace Oregon; they do it to help children in need.

The placement crisis is now compounding itself.

"Because there are so few foster homes right now, the homes that do exist are overextended," she said. "They’re asked to take in kids who maybe wouldn’t have fit within their boundaries.”

She said one foster mom recently summed-up the situation perfectly:

"She said, 'You know, if there was a natural disaster in our community and there were hundreds of kids that were wandering around the streets… all of us would be opening our doors saying yes, come in,'" Gray said. "'... And yet, no one is opening their doors because they just don’t know. It’s like the silent disaster that’s happening on the outskirts.'”

About 11,000 Oregon children, or a little more than 1 percent of the state's youth population, pent at least one day in some kind of foster care last year.

Embrace Oregon and other organizations are looking for new foster care homes, but they also need volunteers to drive kids around or just sit with them for a few hours.