An Oregon

of the state's Smarter Balanced standardized exams found that the tests aren’t well understood, and that they take up scarce time and resources in schools.

The legislature called for the audit of the Smarter Balanced exam – as teachers raised questions and many parents withdrew their kids from taking it. Secretary of State Jeanne Atkins said state officials value the exams, often more than teachers and parents do.

“The Department of Education needs to take the lead on having good conversations with school districts, with teachers and with parents about ‘why this test, what this test is like, and what accommodations will be made going forward’,” Atkins said.

Oregon started using Smarter Balanced in the spring of 2015, as the federally-required exam for students in grades three through eight, and high school. The exams are intended to track how schools are doing at educating students — but high-level administrators suggest the testing is supposed to have value beyond that. The Secretary of State audit suggested teachers and parents are not clear on the additional value of the test.

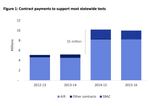

The cost to the Oregon Department of Education of the mandatory state exam nearly doubled from $5.2 million in 2013-14 to $10.2 million in 2014-15, as the state changed to the Smarter Balanced (SBAC) exam. Much of the money went to outside contractor, American Institutes for Research (AIR).

Oregon Secretary of State

The exams are aligned with Common Core State Standards, a controversial set of learning objectives adopted in Oregon several years ago. Those standards have sparked controversy in many states. In Oregon, the tests themselves have been a target of opposition. The U.S. Department of Education has a 95 percent participation requirement. Portland Public Schools achieved only about 90 percent participation; Lake Oswego also fell short of 95 percent. Oregon legislators passed a law in 2015 clarifying that students could opt out of the exams for any reason (the previous law had allowed students to avoid the test only if they had objections based on religion or disability).

The most recent results from Math and English Language Arts exams that students took last spring show virtually the same results as the first round in 2015: 55 percent of students passed the ELA portion of the exam, and 42 percent of students passed the Math. Enormous achievement disparities appeared, based on race and income.

The audit confirmed some of the criticisms teachers and parents have been leveling at the exams since they were introduced last year.

The audit concluded that the results of the test are not used consistently across Oregon's 197 school districts.

"Educators told us that it would be easier to use results if they received them sooner," the audit said. "Many reported that additional guidance on how to use results would be helpful. Some also reported that a more comprehensive assessment system would be useful."

Related: Class Of 2025: Follow Students From 1st Grade To Graduation

Oregon's previous test — the Oregon Assessment of Knowledge and Skills — would give students and educators immediate feedback. Smarter Balanced has sections that need to be graded individually, and take longer to yield results. Couple that with a testing window in the spring, and teachers frequently complain that they don't get results until after the end of the school year.

The Oregon Department of Education responded to that criticism, saying that response times improved considerably from 2015 to 2016.

"ODE made significant improvements in test results delivery time in the second year of administration (2015-16)," said Deputy Superintendent Salam Noor in his response to the audit. "For example, most test results were scored and returned to school districts no later than 14 days from the time a test was completed, with many scores returned within a matter of days. In fact, more than 99 percent of the tests that were started prior to May 15, 2016 were returned to school districts by June 1, 2016."

The audit also found tests demanded time and computer resources that are already in short supply at schools. It also stretched teachers, and forced some administrators to bring in additional staff.

"Coordinating and administering the test takes staff time. This includes supervising students who finish early or opt out of testing," the audit said. "Some principals hired new staff or substitutes, while others said they absorbed increased staffing needs with existing staff. Staff may be taken from other duties, including teachers, administrators, instructional coaches, librarians, counselors and specialists."

To the extent that instructional time is lost to allow time for the lengthy Smarter Balanced exams, the audit suggests struggling students lose the most instructional time.

"We heard concerns from educators about how some student populations may experience the test differently than other students, including concerns about students missing additional services or instruction, students experiencing additional stress, negative impacts to students’ self‐esteem, and concerns about whether Smarter Balanced is fair for all students," the audit said. "Educators told us that they have questions about the fairness and validity of the test."

Among the audit's recommendations is a call for the state to look into a more varied set of assessments - including classroom-level quizzes and midterms that would provide results more useful to educators.

The audit’s release coincides with a report from a state work group emphasizing the need to diversify testing – to include classroom-level assessments more naturally geared toward improving instruction.

ODE agreed with diversifying the approach to assessment in its response to the audit.

"We will provide resources and capacity-building for Oregon schools in using both formative and interim assessment practices as well as statewide summative assessment results," Noor said in his response to the Secretary of State audit. "This will allow local educators to both inform instructional decisions at the individual student level and engage in meaningful evaluation of program effectiveness to drive improved student outcomes for Oregon students."

Noor points to a plan called "A New Path for Oregon: System of Assessment to Empower Meaningful Student Learning," that resulted from a group of education officials and advocates in Oregon, including Oregon's former Chief Education Officer Nancy Golden and the Oregon Education Association.