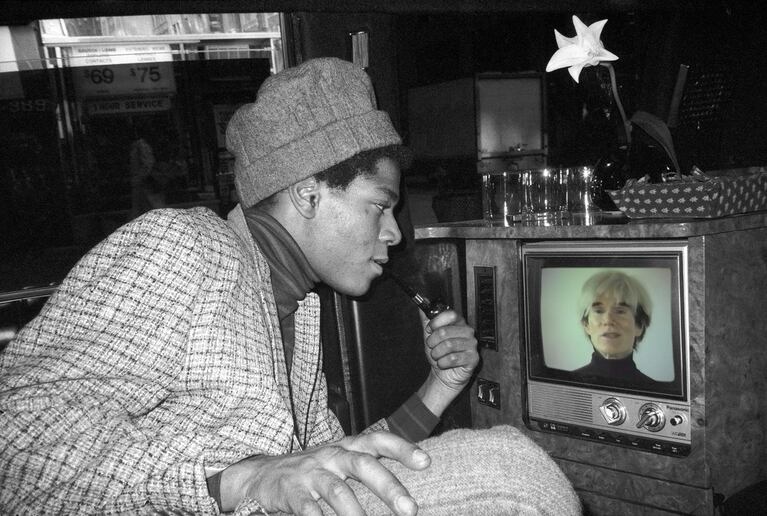

Jean-Michel Basquiat appears to watch a video of Andy Warhol in IPaige Powell's installation "The Ride" at the Portland Art Museum.

Paige Powell / Portland Art Museum

When Portland-native Paige Powell worked at Interview Magazine in New York City in the 1980s, she traveled in rarefied circles. There were lunches with Bianca Jagger, dinners with David Bowie or Bob Dylan, and an endless parade of parties with Andy Warhol. And she documented it all with her camera.

Then, when she moved back to Oregon, she put all the photos and videos in boxes and didn’t look at them for years.

Now she’s showing them for the first time in an installation at the Portland Art Museum called “

” through Feb. 21.

Powell, a fifth-generation Oregonian, moved to New York City in 1980 with the express purpose of working for either Interview Magazine or Woody Allen. She landed both, but went with Interview because it started earlier.

“They said, ‘Have you ever sold anything?’ And I said, 'Yes,’ that I had sold elephant manure, Zoo Doo, at the Washington Park Zoo,” Powell said of how she convinced Interview founder Andy Warhol and his team to hire her. “And they said, ‘Wow, if she can sell elephant dung, maybe she can sell some ads for Interview magazine.’”

Those days at Interview and Warhol’s factory are now the stuff of art legend. Staff came to work in ballgowns worn to parties the night before. They took limos to fancy meals but couldn’t afford hot water in the office. Leading artists were constantly coming through, if not working for the magazine. And they organized celebrity-studded lunches, to which Powell would invite potential advertisers.

“Wherever Andy went, Paige went,” said Kenny Scharf, one of the tight-knit circle of artists around Warhol. Powell invited Scharf to set up his psychedelic “Cosmic Cavern” outside “The Ride.”

And wherever Powell went, she took a camera, influenced by Warhol’s idea of recording without a purpose.

“They just went into a box,” said Powell of the photos she took. “I didn’t even see the video after I shot it. I never looked at it. I just threw it into boxes.”

Warhol died in 1987. Powell moved back to Oregon a few years later to dedicate herself to animal rights advocacy. The boxes filled her house and garage.

“I couldn’t look at them — it was just too overwhelming,” Powell said. “I would get stuck looking at photographs of maybe somebody who died of AIDS or a drug overdose. It just made me depressed and sad — I couldn’t do it.”

Her friend Thomas Lauderdale, the bandleader of Pink Martini, encouraged her. He finally took the boxes to his loft and hired archivists to go through them.

The result is “The Ride.”

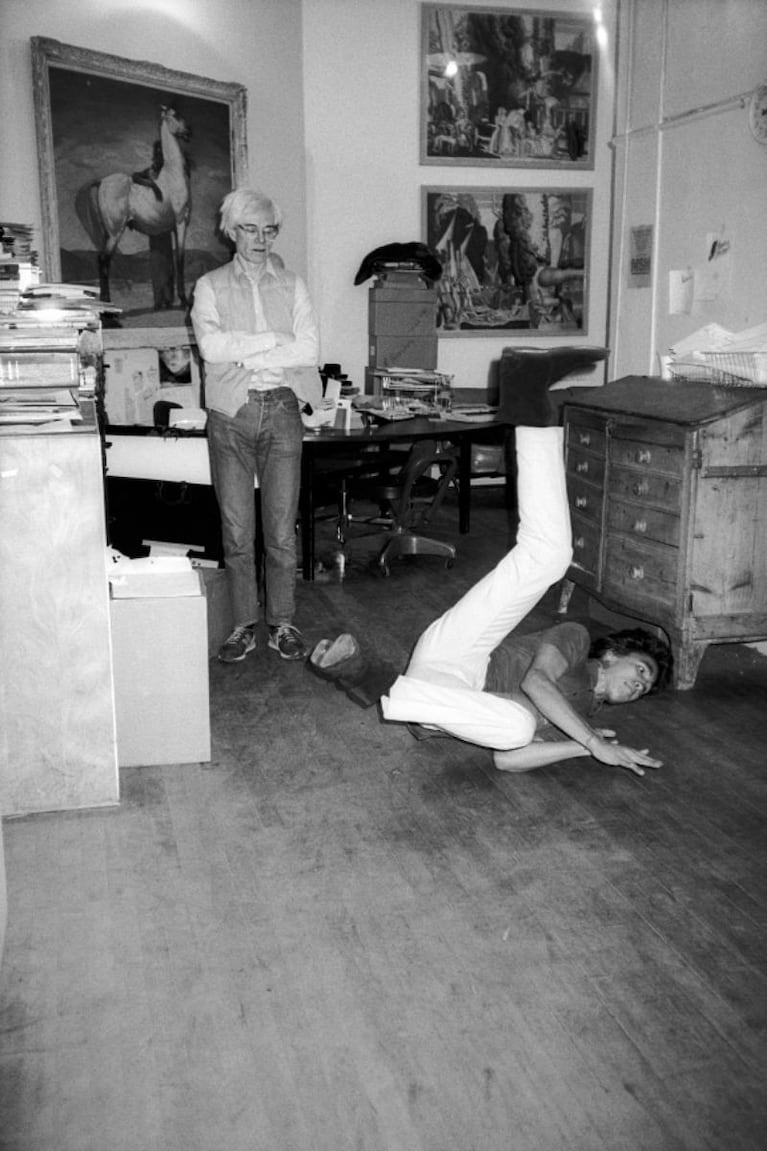

Three projections of black-and-white photos of the artist Jean Michel Basquiat line one wall of the black, rectangular room. He sits in the back seat of a limo holding a pipe and leaning towards the built in TV. Powell has inserted three never-before-seen videos she filmed herself into the television screens, so it’s like Basquiat is watching her videos. One shows Keith Haring painting an elephant statue, one follows Andy Warhol shopping, and one is Warhol talking to her about a party.

A big cubby off the main room is plastered with more than 800 of Powell’s photographs. To scan them is to test your 80s knowledge: Is that a young Madonna looking like a hipster librarian? Is that Grace Jones in a fur hat? What were Sting, Bob Dylan and Warhol talking about over wine? Who’s that drag queen standing next to Bill Cunningham? And then there are a number of newer photos of Powell’s life and friends, from Lauderdale to director Gus Van Sant.

The show is a recreation of one she did at a small New York art bar in 1984 called Beulah Land.

When asked whether she had a sense at the time that she was documenting a period that would become the subject of countless documentaries, books and retrospectives, Powell said she had no idea.

“I never did anything with a purpose,” she said. “Now a lot of young people, everything has to be done for achieving a number of hits on their website or their Twitter account or Instagram. Back then you just did it because you wanted to. It was all about creativity.”

Powell will share these stories and more in "Stops Along The Ride," a conversation with museum director Brian Ferriso on Nov. 19.